Unknown, Cameo set into a ring, 1st century A.D. Sardonyx set in modern gold ring. Greatest extent: 1.8 cm (11/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California

LOS ANGELES, CA.- Carved gemstones have captivated connoisseurs and collectors of every age, from antiquity to the present. Carvers and Collectors: The Lasting Allure of Ancient Gems, on view from March 19 – September 7, 2009, at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa, brings together remarkable intaglios and cameos carved by ancient master engravers along with outstanding works by modern carvers they have inspired.

The exhibition will display ancient gems together with items from later periods that illustrate the importance of gems through the ages. Illuminated manuscripts, rare engravings from early catalogues, and cabinets designed to house collections of gems as well as other works of art in diverse media will also be included.

“Greek rulers, Roman emperors, medieval and Renaissance popes and potentates, and 17th–19th-century monarchs and aristocrats all sought to possess these precious markers of culture, taste, and status,” said Kenneth Lapatin, associate curator of antiquities. “This exhibition truly illustrates the lasting allure of these masterpieces in miniature.”

Semi-precious hard stones, like carnelian, chalcedony, amethyst, and agate, have long been carved with decorative patterns and figural designs. Skilled craftsmen in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt as well as Greece, Rome, and Etruria used hand-powered drills and lathes to cut images into stone to create exquisitely carved gems.

Ancient gem forms called intaglios––from the Italian “to cut in”–– were produced through a technique that used negatives to create positive reliefs, or impressions, when pressed into a soft material, such as wax or clay.

Around 400 B.C., a new technique developed alongside intaglios––the making of cameos. Carvers created relief images that were produced by cutting away the stone surrounding the figure. By exploiting the different colors of banded stones, which could be artificially enhanced, artisans created the illusion of depth with multi-colored compositions.

Engraved gems have been valued not only for their distinctive carving, but also for the intrinsic qualities of their stones. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, ancient intaglios and cameos were reused not only as rings and pendants, but also were mounted in reliquaries, book-bindings, and altar pieces. Rulers, noblemen, and wealthy merchants sought and traded gems, and modern carvers produced replicas and forgeries.

Ancient gem carvers occasionally signed their works, but very few are recorded in ancient literature. However, unsigned intaglios and cameos have in many cases been attributed to known masters through their shared characteristics.

Master carvers on display in this exhibition include Solon, active about 70–20 BC, who worked in Roman imperial circles. Recently, one of his signed gems was found in excavations at Pompeii. His carvings gained great popularity in the 18th century due to the exceptional quality and design of his “Strozzi Medusa” gem, which appears in the exhibition.

Also included are gems attributed to Dioskourides, a Greek master from Aigeai, mentioned by several Roman authors as the carver of the Emperor Augustus’ personal seal.

Carvers and Collectors: The Lasting Allure of Ancient Gems is curated by Kenneth Lapatin, associate curator in the Department of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Youth Adjusting His Sandal, Attributed to Epimenes. Greek, Cyclades, about 500 B.C. Carnelian. 5/8 x 3/8 x 5/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

Epimenes

Epimenes was a Greek carver active around 500 B.C. The exhibition includes one gem signed by Epimenes, along with four unsigned gems attributed to him. Similarities in material, technique, and style provide strong evidence for these attributions.

This gem with a standing youth is unsigned, but details such as the arm and leg muscles and the crosshatched hair with pellets representing ringlets are close enough in style to the only surviving gem signed by Epimenes to indicate that he carved it.

Youth Scraping His Leg with a Strigil, attributed to Epimenes, about 500 B.C. Obsidian scaraboid intaglio set in a modern gold ring, 5/8 x 1/2 x 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AN.370.6

This gem has no signature but is attributed to Epimenes.

Youth Taming a Horse, signed by Epimenes, about 500 B.C. Chalcedony scaraboid intaglio, 3/4 x 9/16 x 3/8 in. Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

This gem is inscribed in Greek: "Epimenes made [this]."

Attributed to Solon, Engraved Gem, Early 1st century A.D. Amethyst (in Neoclassical gold mount) Object: H: 3.3 x W: 3 cm (1 5/16 x 1 3/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California

Solon

The ancient Greek gem carver Solon (active 70–20 B.C.) worked in Roman imperial circles, fashioning idealized portraits of the emperor Augustus and his sister, along with images of mythological figures. Solon's signature is preserved on five ancient gems, including the so-called Strozzi Medusa (also on view in the exhibition). His carvings gained great popularity in the 18th century due to the outstanding quality of that intaglio, which was copied by modern artists in diverse media.

More recently, several unsigned stones, including the one shown here, have been attributed to his hand.

Apollo, attributed to Solon, 30–20 B.C. Fragmentary amethyst intaglio repaired and set in a modern gold mount, 1 5/16 x 1 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Gift of Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman

The Strozzi Medusa by Solon (detail), Bernard Picart, engraving in Baron Philipp von Stosch, Pierres antiques gravées, sur lesquelles les graveurs ont mis leurs noms...) (Ancient Engraved Gems, on Which Carvers Have Inscribed Their Names...), Amsterdam, 1724. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, 81-B171

Dioskourides and Sons

Dioskourides (active 65–30 B.C.), a Greek master from Aigeai in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), is one of the few gem carvers recorded in ancient literature. He is mentioned by several Roman authors as the carver of the personal seal of the emperor Augustus (ruled 27 B.C.–A.D. 14). Dioskourides' fame led later carvers to copy his works and forge his signature.

This intaglio showing the Greek hero Diomedes stealing the Palladion (a talismanic statuette of the warrior goddess Athena) is among the finest of all gems that survive from antiquity. In a field of just a few centimeters, Dioskourides convincingly rendered details of a dynamic, living body, clearly distinguishing skin, muscle, bones, and even fingernails.

In 1856 the gem was mounted into a bandeau with a pseudo-Renaissance enamel setting.

Bandeau featuring Diomedes and the Palladion. Central gem by Dioskourides (Greek, 40–30 B.C.). Carnelian intaglio mounted in gold with colored enamel, diamonds, and other ancient engraved gems. Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Image © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

Dioskourides. Greek, 40–30 B.C. Carnelian intaglio mounted in gold with colored enamel and other gems. 11/16 x 11/16 in. Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Image © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

Diomedes and the Palladion by Dioskourides (detail), Bernard Picart, engraving in Baron Philipp von Stosch, Pierres antiques gravées, sur lesquelles les graveurs ont mis leurs noms...) (Ancient Engraved Gems, on Which Carvers Have Inscribed Their Names...), Amsterdam, 1724. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, 81-B171

Dioskourides' sons, Eutyches, Hyllos, and Herophilos, followed him in the gem-carving trade.

This cameo by Hyllos depicting a satyr—a part-human, part-horse or -goat companion of the wine god Dionysos—shows the finely detailed carving that is characteristic of his and Dioskourides' work.

Satyr, Hyllos, Greco-Roman, 10 B.C.–A.D. 10. Sardonyx cameo. 11/16 x 9/16 in. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

Gnaios

Although he signed his gems in Greek, the ancient carver Gnaios (active 40–20 B.C.) actually had a Latin name, Gnaeus. This does not mean that he was Roman, for Latin names were sometimes adopted by Greek artisans. The exhibition includes all four gems bearing Gnaios's signature that survive from antiquity—stunning intaglios of rulers and mythological figures.

This intaglio of the Roman general Mark Antony (83–30 B.C.) softens the harsh features seen on coins with his image. It may be a posthumous portrait commissioned by his daughter, Cleopatra Selene (40 B.C.–A.D. 6), whose husband, the North African king Juba II, was an avid gem collector. The gem was set into a ring in the 19th century.

Mark Antony, Gnaios, 40–20 B.C. Amethyst intaglio set in a modern gold ring. 11/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

In antiquity, gems were engraved with personal or official insignia that, when impressed on wax or clay, were used to sign or seal documents. Carved gems were valued not only for their distinctive designs, but also for the beauty of their stones, some of which were believed to have magical properties.

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, rulers, nobles, and wealthy merchants

"For a great many people, a single gemstone alone is enough to provide the highest and most perfect aesthetic experience of the wonders of nature."

—Pliny the Elder, Natural History, before A.D. 79

Carved gemstones have captivated connoiseurs of every age, from antiquity to the modern period. This page describes eight of the most avid and influential European gem collectors from the Renaissance to the early 1900s.

Pietro Barbò (Italian, 1417–1471)

The collector Pietro Barbò, who became Pope Paul II in 1464, possessed one of the largest and most completely recorded assemblages of art in 15th-century Italy. The inventory of his collection, written in Latin and divided into 32 sections, catalogues over 3,300 objects, ranging from Byzantine textiles to liturgical silver. Each item was accompanied by a description of its monetary value, iconography, and aesthetic and historical significance. Barbò's 827 ancient gems were organized under four categories: cameos, intaglios with heads of men, intaglios with heads of women, and intaglios with full-length figures. His gems, which he often mounted on rings, fascinated his contemporaries—who asserted after his death that he kept spirits in his rings and had been strangled by one of them. Although he possessed a massive number of gems, Barbò was most interested in numismatics; it was claimed that upon seeing a coin, he could instantaneously identify the emperor or empress represented.

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640)

A prolific artist famous for his Baroque altarpieces, portraits, and paintings of mythological scenes, Peter Paul Rubens was also a humanist scholar and a collector of antiquities. Born in Westphalia (a region of West Germany), Rubens moved to Antwerp, Belgium, after his father's death in 1589 and became a master in the Antwerp painter's guild in 1598. Two years later he departed for Italy, where he spent eight formative years working in Mantua and Rome and studying Renaissance frescoes and classical antiquities.

While abroad, Rubens began to collect ancient gems and marbles, and when he returned to Antwerp, he continued to expand his holdings through agents and friends. The commercial side of collecting appealed to the painter, and he sometimes resold parts of his collection or exchanged objects for others. One noted sale took place in 1626, when Rubens sold 196 of his gems to the first Duke of Buckingham. He was careful to withhold some of his favorites, such as the famed gem of the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche by Tryphon, which he bequeathed to his son Alfred. In general, Rubens was extremely secretive about his gems and was unwilling to show them to visitors, fearing that they would be counterfeited.

Thomas Howard (British, 1585–1646), Second Earl of Arundel

A consummate collector, Thomas Howard acquired a wide variety of objects, ranging from paintings by Italian Renaissance masters to animal pelts and butterflies. Traveling extensively, Arundel came into contact with artists and scholars who helped him build his collections. During a 1613 visit to Rome, a leading art patron arranged for him to visit the Forum, where he "discovered" ancient statues planted there beforehand. These sculptures formed the basis of the antiquities collection at Arundel House. The earl was also keen to obtain ancient gems. In 1637 he purchased 263 cameos that had reportedly belonged to the dukes of Mantua for ten thousand pounds. The group included the famous Felix Gem displayed in this exhibition.

At the time of his death, the quantity of Arundel's acquisitions was astonishing. He owned, for example, 40 paintings by Holbein, 37 by Titian, 13 by Raphael, and over 600 drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. Although the earl's collection appears exceedingly complete, he failed to obtain one coveted object: an ancient Roman obelisk. Arundel's agent, William Petty, could not get an export license for it, and the granite monolith was eventually used by the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini as the center of his Four Rivers Fountain in Rome.

William Cavendish (British, 1672–1729), Second Duke of Devonshire

William George Spencer Cavendish (British, 1790–1858), Sixth Duke of Devonshire

The Devonshire collection, which numbers over 500 gems and is still at the family estate at Chatsworth, was begun by William Cavendish, the second Duke of Devonshire, in the late 1600s. He commissioned drawings of his ancient gems to make them more generally available—a rare objective for collectors of his era. One of the duke's most treasured acquisitions was a fragment of a carnelian intaglio depicting a cow and signed by Apollonides, a Greek carver mentioned in the writings of Pliny the Elder, for which he paid the hefty sum of one thousand pounds.

The second Duke's extravagance was surpassed by William George Spencer Cavendish, the sixth Duke of Devonshire, who spent so much on his collections and the construction of his gallery that he fell into debt and was forced to sell off some of his estates. Although the sixth Duke did not add many new pieces to the gem collection, preferring to acquire libraries, coins, and medals, he commissioned a suite of jewelry that framed 88 ancient gems with garnets, sapphires, emeralds, amethysts, and many of the family diamonds. Known as the Devonshire Parure, the jewels were fashioned for the Countess Granville, wife of the duke's nephew, to wear to the coronation of Czar Alexander II.

Baron Philipp von Stosch (German, 1691–1757)

A prominent antiquarian and art dealer, Baron Philipp von Stosch authored a seminal publication on ancient gemstones. Born in Brandenburg, he settled in Rome in 1717, where he collected gems, books, manuscripts, and drawings. His holdings included over ten thousand ancient intaglios, cameos, and glass pastes. Von Stosch financed his collection through rather unorthodox means, working as a spy for the British government of Robert Walpole on the Jacobite Court in Rome. In 1724 he published Pierres antiques gravées, sur lesquelles les graveurs ont mis leurs noms... (Ancient Engraved Gems, on which Carvers Have Inscribed Their Names...) a catalogue of gems he considered genuine, inscribed with proper names he claimed as artists' signatures. From that moment on, there was a great demand from aristocratic collectors for signed gems. When von Stosch's cover as a spy was blown in 1731, he fled the Papal States and took up residence in Florence, living on a pension from the British. He devoted the rest of his life to connoisseurship and to supporting young German artists, such as the gem engraver Johann Lorenz Natter.

George Spencer (British, 1739–1817), Fourth Duke of Marlborough

A learned aristocrat whose interests ranged from civil law to astronomy, George Spencer was also a distinguished art collector. After the second Earl of Arundel died in 1646, his gem collection was sold and eventually ended up, through inheritance, in the hands of Lady Diana Beauclerk, Marlborough's sister-in-law. She then transferred Arundel's gems to Marlborough, who incorporated them into his existing holdings of 300 specimens.

The duke purchased his gems at auctions and through contacts in Rome and Venice, who reserved their best items for him. His methods of acquisition aroused resentment among other collectors, particularly the French, who accused him of bribing and bullying art dealers to obtain the highest-quality works. Marlborough was extremely proud of his gems, which he enhanced with lavish jeweled settings and stored in red Moroccan leather boxes. At the time of his death, he possessed nearly 800 pieces. When the family finances became troubled several decades later, the collection was sold, and in 1899 it was dispersed through separate auctions at Christie's.

Edward Perry Warren (British, 1860–1928)

The collector Edward Perry Warren was born in Massachusetts to a family that made its fortune from a paper mill. After graduating from Harvard, Warren vowed to spend the rest of his life abroad and pursued an advanced degree at Oxford. There he met men similarly interested in studying and collecting antiquities, including his life partner, John Marshall. In 1890 Warren began to lease Lewes House, a historic Georgian estate in Sussex, where he lived with Marshall and six other men in pursuit of scholarship and collecting. Visitors observed that Lewes House was rather odd, "a monkish establishment" where everything was shared and little interest was taken in the affairs of the outside world. Despite the closeness between members, the brotherhood broke up after 12 years. Marshall married Warren's cousin Mary Bliss in 1907—a great blow to Warren—but after her death in 1925, the two men reunited for the remaining years of their lives.

Augustin de Saint-Aubin after Charles-Nicolas Cochin II, French. Engraving in François Arnaud, Description des principales pierres gravées du cabinet de S.A.S. Monseigneur le duc d'Orléans... (Description of the Principal Engraved Gems in the Cabinet of His Serene Highness, the Duke of Orleans...) (Paris, 1870). Research Library, The Getty Research Institute. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

Gem Catalogues

Sumptuous engraved catalogues of gem collections were published in the days before photography. Like the gems they illustrated, these volumes functioned as luxury objects. The engravings in these books sometimes improve upon the already excellent carving of the gems themselves.

Louis Philippe d'Orléans (1725–1785), the great-grandson of King Louis XIV of France, published his gem collection in an elaborately engraved volume dedicated to his cousin King Louis XVI. The frontispiece, shown here, depicts the duke himself and also represents the superiority of gems over other art forms: in the foreground, two cupids inspect the contents of drawers pulled from a large gem cabinet, while symbols of architecture, sculpture, and painting are relegated to the upper right and lower left corners.

Daktyliotheke (Gem Cabinet) with Impressions. Workshop of Pietro Bracci. Italian, about 1825. Wood, leather, plaster, paper, and gold. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

Antonio Pichler and Sons

Austrian carver Antonio (Johann Anton) Pichler worked in Rome in the 1700s copying ancient gems. His son Giovanni also became an accomplished gem carver, as did Giovanni's half-brothers Giuseppe and Luigi and Giovanni's son Giacomo. Luigi was the most renowned: he received commissions from the Vatican and the French and Austrian courts to carve both classical and contemporary subjects.

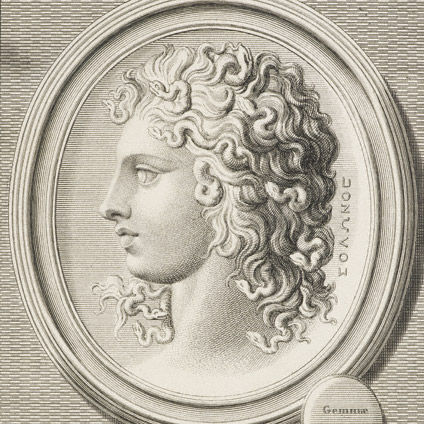

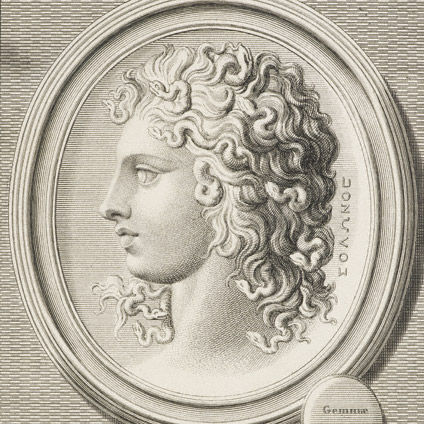

This intaglio is modeled after a famous relief of Antinous (the beloved of the Roman emperor Hadrian) housed in the Villa Albani, Rome. The fact that the gem is signed "Pichler" in Greek indicates no intention to deceive but rather an emulative spirit, the artist vying with his ancient predecessors.

Initial D: Saint John the Baptist (detail). Matteo da Milano. Italian, Rome, about 1520. Tempera and gold on parchment. 13 1/4 x 9 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Trust © J. Paul Getty Trust

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F75%2F577050%2F66348259_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F47%2F53%2F119589%2F62846026_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F17%2F23%2F119589%2F61839898_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F48%2F577050%2F61815881_o.jpg)