Forty Exceptional Works will be Offered at Christie's Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art

Tamara De Lempicka (1898-1980) Portrait du Marquis Sommi, signed 'T.DE LEMPITZKA' (lower right), oil on canvas,

39 3/8 x 28¾ in. (100 x 73 cm.) Painted in 1925. Est. $2,000,000 - $3,000,000. Photo Image 2009 Christie's Ltd

NEW YORK, NY.- Rare and important works by Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, and Piet Mondrian are among the highlights of Christie’s upcoming Evening Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art on November 3. Forty exceptional works will be offered, including paintings, drawings, and sculpture. The sale is expected to achieve in excess of $68 million.

Highlights of the sale include:

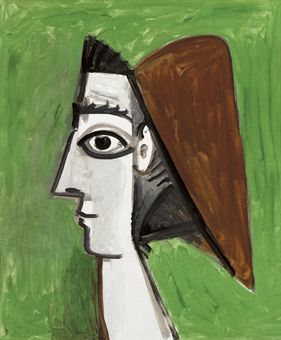

• "Tête de femme", 1943 by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), a vivid portrait of Dora Maar painted during the darkest days of WWII in Paris (estimate: $7-10 million).

• "Danseuses", 1896, by Edgar Degas (1834-1917), a lush pastel drawing of two dancers at rest, one of Degas’ most sought-after subjects (estimate: $7-9 million).

• "Vétheuil, effet de soleil", 1901, by Claude Monet (1840-1926), from an important series of views Monet completed of this picturesque village on the Seine (estimate: $5-7 million).

• "Le Pont du chemin de fer", Pontoise, circa 1873, by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), a luminous and classically composed landscape that captures the essence of early Impressionism (estimate: $3.5-4.5 million).

• "Le Baiser" (The Kiss) by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), an exceedingly rare lifetime cast of one of Rodin’s most celebrated subjects (estimate: $1.5-2 million).

• "Rosace", 1954, by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), the artist’s final major commission; a paper cut-out used as inspiration for a stained-glass window created in memory of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (estimate: $3-4 million).

• "Composition II", with Red, 1926 by Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), one of only two surviving paintings from a pivotal series of works known as the “Dresden Paintings” (estimate: $4.5-6.5 million).

Tête de Femme by Pablo Picasso

Among the most anticipated works to be offered this season is Picasso's vibrant "Tête de Femme" from 1943, a wartime portrait of the artist's muse and mistress Dora Maar. Painted in October 1943 during a period of continued hardship and deprivation in Paris, the portrait is remarkable for its bright, saturated colors and celebratory air -- an effect quite different from the mostly somber-hued portraits by Picasso from the same period. Dora Maar is discernible in the simplified and disjointed face in the painting by her large staring eyes, trademark raven hair (represented here as an elongated dark blue oval), and her customary hat, dressed in this depiction with three flower-like pins and a trailing ribbon.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Tête de femme, signed 'Picasso' (upper right), oil on canvas, 36¼ x 28¾ in. (92.1 x 73 cm.) Painted in October 1943. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Provenance: Private collection (acquired from the artist, 1945).

Carmess Art Gallery, New York.

Galerie Durand-Ruel et Cie., New York (acquired a half share from the above, March 1948).

Dominique Levy, New York.

Acquired from the above by the present owner, circa 1999.

Literature: C. Zervos, Picasso, Paris, 1962, vol. 13, no. 140 (illustrated, pl. 75).

The Picasso Project, ed., Picasso's Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture: Nazi Occupation 1940-1944, San Francisco, 1999, p. 272, no. 43-255 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Paris, Galerie Louis Carré, Dix-neuf peintures de Picasso, June-July 1946, no. IX (illustrated).

New York, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Picasso, 3-29 May 1948, no. 1 (illustrated).

Notes: The severely simplified, jagged and disjointed facial schematic in this painting is certainly in keeping with other wartime portraits by Picasso. There is nevertheless an unusual measure of humor and spontaneous delight in Picasso's characterization of this female sitter, who appears to have been assembled from an assortment of cut and sectioned abstract forms, in a modernist's version of the portraits composed of flora and fauna by the Renaissance master Arcimboldo. For her sake Picasso put aside the often somber tonalities of the wartime pictures, choosing instead to employ bright, saturated colors--the three primaries, with derivative green and related tints--which lend this picture an extrovert and celebratory air. This sense of warmth and good feeling contrasts with the bleak or even brutal aspect of other wartime female portraits; and indeed, it comes as something of a surprise, and stands out among them.

With her large staring eyes, as if transfixed by the artist's gaze, and shoulder-length raven hair, represented here as an elongated dark blue oval, the subject of this portrait is very likely Picasso's wartime muse and mistress Dora Maar (fig. 1). The large and striking hat, to which three large, flower-like pins have secured a long striped ribbon, also points to Dora as the sitter. Such hats had become a regular feature in Picasso's depictions of Dora, functioning as a symbolic externalization of her inner moods. Brigitte Léal has called the hat Dora's "most provocative emblem... In its preciousness and fetishistic vocation, the feminine hat was, like the glove, an erotic accessory highly prized by the Surrealists. Thus Paul Eluard [declared] 'A head must dare to wear a crown.'" (in Picasso and Portraiture, exh. cat., The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996, pp. 387, 389 and 392). Dora's hats acquired an especially belligerent aspect during the early months of the war (Zervos, vol. 11, no. 144; fig. 2), when they sometimes resemble the silhouettes of warships seen on the horizon, a warplane's propeller, or the tail fins of a plunging high-explosive bomb.

In 1954, a decade after their relationship had come to an end, Picasso and Dora met in a rare encounter at a dinner party hosted by Douglas Cooper and John Richardson. In the moments before she arrived, as Richardson has related, "the artist reminisced about Dora--at first affectionately--how the steadfastness of her gaze reflected her intelligence, and how her outré sense of fashion had inspired the surrealist hats trimmed with fish and fruit and sardine cans that figure in many of his portrayals of her--such a contrast, he said, to the tam o'shanter from Hermès that he gave to her rival Marie-Thérèse. Hats differentiate the two rivals in his work. Did the craziness of Dora's hats, by Albouis or Schiaparelli, imply a certain craziness in the sitter? Yes, he thought it did" (in The Sorcerer's Apprentice, New York, 1999, p. 206).

The deepening intimacy of Picasso's liaison with Dora during the late 1930s coincided with the fascist uprising and ensuing Civil War in Spain. In fact, the entire history of their relationship was tragically and inescapably set against the backdrop of violence and war. Dora's darkly intense but inscrutably impassive countenance seemed to reflect the ominous and troubled mood in Europe during the years that preceded the Second World War. Picasso began to subject Dora's visage in his paintings to unsparing savagery; like some mad surgeon he would take her features under his knife and in the course of his experiments contrive some shocking new pictorial identity for her. Richardson has pointed out that "After World War II broke out, Picasso came to portray Dora more and more frequently as a sacrificial victim, a tearful symbol of his own pain and grief at the horrors of tyranny and war" (in "Pablo Picasso's Femme au chapeau de paille," Christie's, New York, sale catalogue, 4 May 2004, p. 113).

Living conditions in Paris became ever more harsh and difficult to bear during 1943 as the German occupation extended into its fourth year. Mme Léal has written, "One might describe this period as a long winter... This cold drove people into themselves, into a total silence... Curfew, glacial winter, and fear were the only items on the menu" (in Picasso and the War Years, 1937-1945, exh. cat., Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1998, p. 85). Parisians had to deal with shortages of every kind, and the coming winter would prove to be especially hard. While Picasso was permitted to paint, he had been forbidden to exhibit. His studio at 7, rue des Grands-Augustins, which he now made his wartime residence as well, had been subject to a Gestapo search, during which the intruders kicked his canvases, were verbally abusive and threatened to return. The police kept his studio under surveillance. Picasso had to put up with unwelcome visits by German officers and ordinary soldiers who professed to an interest in art, even if Picasso's painting was considered to be archly "degenerate" according to aesthetic dictates of the Third Reich.

All sorts of rumors surfaced about Picasso: he had been sent to concentration camp, he was working with the Resistance, or conversely the Germans were protecting the artist and even extending special treatment to him. Picasso soon discovered that he had perniciously hostile detractors among his fellow Parisians, who took advantage of the back-biting, scapegoat-seeking and treacherous climate of the Occupation to rain down aspersions on him and his art. There was even a well-known painter among them--in June 1942 Vlaminck published an article in a collaborationist journal in which he blamed Picasso "for having led French painting into a deadly impasse having led it into negation, helpless and finally to its death" (quoted in A. Baldessari, Picasso: Life with Dora Maar, Paris, 2006, p. 246). On 16 September 1943 Picasso received a summons to report for a physical examination and questioning in preparation for deportation to Germany as a forced laborer. This document appears to have been a forgery, a cruel prank; in any event, Picasso did not respond to it. The German authorities had come to an agreement among themselves that Picasso, the creator of the anti-fascist mural Guernica, could be intimidated to keep him in line, but short of some major transgression on his part, he would not be touched. Doing harm to Picasso, then the world's most famous artist, would have handed the Allies a propaganda victory that the Nazi architects of the New Order in Europe could ill-afford.

By the fall of 1943 there was a steady stream of news worth celebrating; one might actually believe that the tide of war had turned decisively in the Allies' favor, and that ultimate victory was only a matter of time. The encircled German Sixth Army had surrendered to the Russians at Stalingrad in February, and Soviet armies had begun their westward advance. The Americans and British had overrun Sicily and landed on the Italian peninsula at Salerno. Axis Italy surrendered on 8 September, and Mussolini had been placed under arrest. German forces quickly usurped control of the country, however, and restored its fascist dictator, but everywhere German forces were being forced to take a defensive footing, as the territory of their early conquests was rapidly shrinking. Massive Allied air raids were punishing the German homeland by day and night.

The year 1943 would also prove memorable for Picasso for another, entirely personal, reason. In May he met an interesting new woman, at twenty-two far younger and less emotionally complex than Dora: this was Françoise Gilot, an aspiring art student who had come to his studio seeking advice. She visited Picasso, sometimes with a girlfriend, a few times that spring before leaving Paris on her summer holiday. She did not call on Picasso again until 26 November, her birthday. This hiatus should rule out Françoise as a possible subject for this painting, which was done in October, while she was away, and when there was no certainty she would reappear at Picasso's door. There is moreover no mention in Françoise's memoir Life with Picasso, published in 1954, that the artist had painted her during this early phase of their developing friendship.

Picasso may have normally cast Dora as the archetype of the aggrieved and suffering female martyr in many of his most memorable paintings during the war years, but he also depicted Dora in numerous canvases that reflect pleasant moments of tenderness and subdued joy. One occasion of which Picasso held especially fond memories was an extended vacation with Dora and a close circle of their friends during the summer of 1937, when they stayed at the Hôtel Vaste Horizon in the town of Mougins on the Côte d'Azur. Picasso had recently completed Guernica, whose progress Dora had documented in photographs. The type of gaily striped ribbon seen in the present portrait also features as an accessory of the headwear Picasso included in the portraits that he painted that summer of one member of his entourage, the photographer Lee Miller, whom he depicted in the costume of an Arlésienne (Picasso Project, no. 37-191; fig. 3). This subject carries strong connotations of Picasso's admiration for Van Gogh (Faille, no. 488; fig. 4). During one of their wartime conversations about painting, Picasso told Françoise Gilot, "Beginning with Van Gogh, however great we may be, we are all, in a measure, autodidacts--you might say primitive painters. Painters no longer live within a tradition and so each one of us must create an entire language... from A to Z" (quoted in F. Gilot, with C. Lake, Life with Picasso, New York 1954, pp. 74-75).

The present painting may signify a pleasant if fleeting reminiscence of that golden, Arcadian pre-war summer in Provence six years earlier, when his liaison with Dora was less than two years old--a time more suited to the use of brilliant, sunny color, all in marked contrast to the dreary darkness, in both substance and spirit, of occupied Paris. Mme Léal has written, "the innumerable, very different portraits that Picasso did of [Dora] remain among the finest achievements of his art, at a time when he was engaged in a sort of third path, verging on Surrealist representation while rejecting strict representation, and, naturally, abstraction. Today, more than ever, the fascination that the image of this admirable, but suffering and alienated face exerts on us incontestably ensues from its coinciding with our modern consciousness of the body in its threefold dimension of precariousness, ambiguity and monstrosity. Picasso tolled the final bell for the reign of ideal beauty and opened the way for the aesthetic tyranny of a sort of terrible and tragic beauty, the fruit of our contemporary history" (ibid., p. 385).

Additional Picasso works in the sale include "Mère et enfant", 1925, a tender depiction of the artist’s son Paulo and his first wife Olga Khoklova, (estimate: $600,000-800,000); "Courtisanes et toreros", 1959, a humorous pen and ink drawing of off-duty bullfighters (estimate: $600,000-800,000); and "Visage féminin", profil from 1960, a late-career portrait of Jacqueline Roque painted a year before her marriage to Picasso (estimate: $600,000-900,000).

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Mère et enfant, signed and dated 'Picasso 25' (upper left) oil on canvas, 9 3/8 x 7½ in. (23.8 x 19 cm.) Painted in 1925. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Courtisanes et toreros, dated '16.8.59.' (upper right); dated again 'Domingo 16-17. Aôut 59.' (on the reverse) pen, brush and India ink on paper, 19¾ x 25 5/8 in. (50.2 x 65.1 cm.) Executed on 16-17 August 1959. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Visage féminin, profil, dated '19.2.60' (on the reverse) oil on canvas, 21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in. (55 x 46.1 cm.) Painted on 19 February 1960. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Le Pont de chemin de fer, Pontoise by Camille Pissarro

Of the many notable paintings that Pissarro made in and around Pontoise in the years 1872 and 1873, Le Pont de chemin de fer, Pontoise, remains a stand-out. Paintings of this period have been called the most purely Impressionist of Pissarro's entire oeuvre, and here the artist used mixtures of pure color to achieve a carefully composed landscape with luxurious qualities of light. Pissarro's chosen view takes in the river Oise, as seen from just below the town of Pontoise, with the railway bridge visible in the near foreground. Rather than painting the modern railway as an imposition upon the quaint and verdant landscape, Pissarro has subtly integrated the iron bridge and its traffic into the surroundings, so that it becomes a landscape feature seen fully within the context of the enduring natural world.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) Le Pont du chemin de fer, Pontoise. signed 'C. Pissarro' (lower left), oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 25 5/8 in. (50 x 65 cm.). Painted circa 1873. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Provenance: Fromentin; sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 16 December 1908, lot 10.

Anon. sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 3 December 1910, lot 46.

Eugène Blot, Paris (acquired at the above sale).

Galerie Bernheim Jeune et Cie., Paris (circa 1916).

Gérard Frères, Paris.

M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., New York (acquired from the above, January 1924).

James Carstairs, Philadelphia (acquired from the above, March 1924).

M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., New York (acquired from the above, October 1927).

Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York.

Ruth S. and David M. Heyman, New York (acquired from the above, before 1945); Estate sale, Christie's, New York, 16 May 1984, lot 12.

The Lefevre Gallery (Alex. Reid & Lefevre, Ltd.), London (acquired at the above sale).

Acquavella Galleries, Inc., New York.

Private collection, London.

Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York (1988).

The Hal Wallis Foundation, Santa Barbara (acquired from the above, 1994); sale, Christie's, New York, 14 May 1997, lot 17.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: L.-R. Pissarro and L. Venturi, Camille Pissarro, son art--son oeuvre, Paris, 1939, vol. I, p. 112, no. 234 (illustrated, vol. II, p. 46).

R. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure and Parisian Society, New Haven, 1988, p. 226 (illustrated in color).

R.R. Bretell, Pissarro and Pontoise: The Painter in a Landscape, New Haven, 1990, pp. 65 and 158 (illustrated in color, pl. 63, pp. 67-69).

R. Katz and C. Dars, The Impressionists in Context, New York, 1991, p. 85 (illustrated in color).

C. Lloyd, "Paul Cézanne, Pupil of Pissarro: An Artistic Friendship," Apollo, November 1992, pp. 284 and 289.

M. Reid, Pissarro, London, 1993, p. 143, no. 83 (illustrated in color, p. 83).

S. Roffo, Camille Pissarro, Paris, 1994, p. 26 (illustrated).

P.H. Tucker, Claude Monet, Life and Art, New Haven, 1995, p. 73, no. 80 (illustrated in color).

B.E. White, Impressionists Side by Side, New York, 1996, p. 120 (illustrated in color, p. 121).

M.J. Pellé, 'Vert Pissarro...' Impressions de Normandie et d'ailleurs, Luneray, 2000, p. 74.

J. Pissarro and C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro, Catalogue critique des peintures, Paris, 2005, vol. II, p. 240, no. 305 (illustrated in color).

Exhibited: Paris, Galerie Knoedler, Peintres de l'École française du XIXe siècle, May 1924, no. 23.

New York, Wildenstein & Co., Inc., Camille Pissarro: His Place in Art, October-November 1945, p. 33, no. 10 (illustrated, p. 24).

Montreal, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Manet to Matisse, May-June 1949, no. 27.

New York, Wildenstein & Co., Inc., C. Pissarro, March-May 1965, no. 22 (illustrated).

London, The Lefevre Gallery (Alex. Reid & Lefevre, Ltd.), Important XIXth and XXth Century Works of Art, June-July 1985, pp. 28-29, no. 13 (illustrated in color).

Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland, French Impressionism and its Origins: Lighting up the Landscape, August-October 1986, p. 78, no. 98 (illustrated in color).

Santa Barbara Museum of Art (on extended loan, June 1994-February 1997).

New York, The Museum of Modern Art; The Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Paris, Musée d'Orsay, Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865-1886, June 2005-May 2006, no. 86.

Danseuses by Edgar Degas

The sale’s cover lot is Danseuses, 1896, a richly-textured pastel drawing from Degas’ highly-coveted series of drawings on this theme (pictured on page one, left). Degas returned to depictions of ballet dancers during the later years of his career, never tiring of the different poses and interactions created by the female figures. Here, he employs a close-up and tightly cropped view of two dancers at rest, one stretching while the other leans heavily against a wall. The drawing is remarkable for the expressive vigor in the artist’s lines and the sheer brilliance of his densely-layered colors. By this point in his career, Degas has largely dispensed with his early penchant for specificity and detail in favor of the looser, more expressive style employed here.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) Danseuses; signed 'Degas' (lower left) pastel on paper laid down on board, 20 1/8 x 15¾ in. (51.1 x 40 cm.). Drawn circa 1896. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Provenance: Eugène Blot, Paris; sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 10 May 1906, lot 91.

Adolf Rothermundt, Dresden (by 1909).

Ludwig and Margret Kainer, Berlin; sale, Leo Spik, Berlin, 31 May 1935, lot 93.

Private collection.

Thomas Gibson Fine Art Ltd., London.

Mai Art Trading.

Fujikawa Galleries, Inc., Japan.

Private collection (acquired from the above).

Literature: Paul Fechter, "Die Sammlung Rothermundt," Kunst und Künstler, 1910, vol. 8, p. 350.

A. Lichtwark, "Der Sammler," Kunst und Künstler, 1912, vol. 10, p. 237, no. 5 (illustrated).

P.A. Lemoisne, Degas et son oeuvre, Paris, 1946, vol. III, p. 724, no. 1242 (illustrated, p. 725).

R. Gordon and A. Forge, Degas, New York, 1988, pp. 216 and 278 (illustrated in color).

A. Pophanken, ed., Die Moderne und ihre Sammler: Französische Kunst in Deutschem Privatbesitz vom Kaiserreich zur Weimarer Republik, Berlin 2001, p. 227, no. 43 (illustrated).

H. Biedermann, "Die Sammlungen Adolf Rothermundt und Oscar Schmitz in Dresden," Von Monet bis Mondrian, Meisterwerke der Moderne aus Dresdner Privatsammlungen der ersten Hälfte des 20 Jahrhunderts, exh. cat., Palais Brühlsche Terrasse, Dresden, 2006, p. 54, no. 18 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Paris, Didier Imbert Fine Art, Tableaux XIX et XX Siècles, May-July 1985, no. 22 (illustrated).

London, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, 19th & 20th Century Masters and Selected Old Masters, June-July 1987, pp. 16-17.

Osaka and Tokyo, Fujikawa Galleries, Selection of French Masterpieces, April-May 1988, no. 8 (illustrated in color).

Gunma, The Museum of Modern Art, Impressionist Exhibition, September-November 1994, pp. 104-105 and 183, no. 44.

London, The National Gallery and The Art Institute of Chicago, Degas: Beyond Impressionism, May 1996-January 1997, p. 299, no. 37 (illustrated in color, p. 217).

Notes: There are in the pantheon of the great moderns a few artists who lived to an advanced age, whom we hold in high esteem for an accomplishment that is uncommon and profoundly revelatory: their lives' work culminated in an utterly transformed and unprecedented art, whose pronounced characteristics may be perceived to constitute a uniquely distinctive "late style." This late body of work may be so exceptional and forward-looking that it may eventually be understood to constitute a defining moment, a benchmark "state of the art," in the history of modernism. Among the artists of the last century, we especially admire Matisse for the innovation and sheer élan of his cut-outs (see Lot ___), and Picasso, for those irrepressible, life-affirming paintings of his final years, the mosqueteros, which drew huge crowds at the Gagosian Gallery, New York, this past spring. Among the giants of the late 19th century, Cézanne arrived at a late style: his bathers and landscapes bespeak ideas and trends that were to thread their way through successive generations of modern painters down to our own day. Monet's late nymphéas paintings represent the transubstantiation of Impressionism into a vision and experience of the physical world that crosses the threshold into a virtually cosmic and timeless dimension.

In this select group of artists we should rightly include Edgar Degas. Observers had noted early on the presence of a late style in his work; in discussing an exhibition of late works in 1936, Waldemar George was struck by "His tones--false, strident, clashing, breaking into shimmering fanfares without any concern for truth, plausibility, or credibility" (quoted in Degas, exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1988, p. 482). A wider appreciation and deepening understanding of Degas's late style began to emerge within the context of the massive 1988 retrospective of his work. It was not until 1996, however, nearly eighty years after the artist's death, that a thorough and definitive accounting of his late work was finally undertaken, in Degas: Beyond Impressionism, curated by Richard Kendall.

Degas drew Danseuses circa 1896; it is around this time that most commentators mark the emergence of this final phase in his work, which lasted until the artist's eyesight had so seriously deteriorated that he could no longer paint, draw or sculpt in his studio, around 1912. This issue of the artist's visual capacity has limited bearing in the mid-90s, but it is nonetheless a reminder of a significant factor that comes into play in the late work of many elder masters: increasing infirmities of various kinds, as well as the growing apprehension of one's mortality, may contribute immeasurably to the challenge of the task at hand, and require from the artist the ultimate measure of courage and the strength of will to carry on, all factors which will inform to some degree the emotional content as well as the appearance of the artist's production.

When comparing the present pastel to works done in previous decades, one instantly observes that Degas has largely dispensed with his early penchant for specificity and detail, now seemingly dissolved in the boldness of his drawing and the sheer brilliance of color, as the artist strove to distill his subject down to its very essence. Joan Sutherland Boggs has noted, "One fact about which there is general agreement by writers on the late work is Degas's increasing indulgence in the abstract elements of his art. Color becomes more intense and often seems to dominate his paintings and pastels Lines also increased in vigor and expressive power In addition, the very texture of Degas's work seems an immediate expression of the will of the man himself In his interest in and reliance on abstraction, there is a willfulness and a turning to what Degas himself described as 'mystery' in art" (in exh. cat., op. cit., 1988, pp. 481-482).

The subject of the dancer reigned supreme in Degas's late work. About three-quarters of his output during this period are related to the dance, and in the mid-1890s this subject outnumbers all others three-to-one, and his next most frequent theme, the nude, by nearly two-to-one. Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall have noted that "only his images of the female bathers approached [the dancers] in sustained originality and commitment" (in Degas and the Dance, American Federation of the Arts, New York, 2002, p. 231). During this time Degas was also making photographs of dancers (or so the few extant glass plates have been attributed to him; fig. 1), and he even employed his skill as a poet to pen a series of sonnets about dancers.

Degas's interest in the dance no longer took its primary stimulation from the modern color and spectacle of the productions at the Opéra de Paris--his attendance declined after the mid-1880s, and he allowed his backstage pass to lapse. He was now taking a more detached and abstract vantage point, from which he approached, with a deeper historical understanding, the expression of dance as a timeless form. The American collector Louisine Havemeyer recalled a visit to Degas in 1903; she was already the owner of a dozen pastel and charcoal drawings on dancers. "I asked Degas the question--I blush to record it--a question that had often been asked me: "Why monsieur, do you always do ballet dancers?" The quick reply was: 'Because madame, it is all that is left us of the combined movements of the Greeks'" (quoted in ibid., p. 234). Jeanne Fevre, the artist's niece, reported that Degas read the Greek classics in the original; he was "passionate about the world of antiquity" (ibid, p. 238). A frequent visitor to the Louvre, Degas especially admired ancient Greek friezes, as well as free standing sculptures such as the famous Venus de Milo, in which he perceived both movement and serenity. Henri Hertz has cited Degas as saying that his dancers "followed the Greek tradition purely and simply, almost all antique statues representing the movement and balance of rhythmic dance" (ibid., p. 235).

To George Moore, Degas declared "the dancer is only a pretext for drawing" (quoted in exh. cat., op. cit. 1996, p. 134). Paul Valéry described Degas's obsession with drawing: "The sheer labour of drawing had become a passion and a discipline for him, the object of a mystique and an ethic all-sufficient in themselves, a supreme preoccupation which abolished all other matters, a source of endless problems in precision which released him from any other form of inquiry" (in Degas Manet Morisot, Princeton, 1960, p. 64). Charcoal became his sole medium for making drawings. The application of the pastel sticks to paper also constitutes a form of drawing--it is essentially a means of drawing in color--Degas stated, "I am a colorist with line" (quoted in exh. cat., op. cit., 1996, p. 257). His reliance on the use of the pastel medium also assumed pre-eminence during the late period, when it accounts for approximately 90 of all works done in color, far out-numbering his oil paintings on canvas, the medium in which almost all artists choose to make their most fully realized and definitive statements. Taking into account the many hundreds of surviving independent drawings that Degas executed, and adding to them the large number of color works that he commenced with an underlying drawing, it becomes clear how thoroughly the practice of drawing informs the content and presentation of the artist's late works, making Degas's oeuvre unique in this regard among the artists of his time.

Degas's method of working in pastel is perhaps as fascinating to follow, insofar as one can recreate the process, as the product is beautiful to behold. Valéry recalled Degas saying "a picture is the result of a series of operations" (quoted in op. cit., p. 6). The artist began Danseuses with a charcoal drawing done on tracing paper. This drawing itself was likely the result of earlier "operations." The idea for this particular pairing of resting dancers may have come the oil painting La salle de danse, circa 1891 (Lemoisne, no. 1107; fig. 2), where they appear just to the right of the post that bisects the composition. A series of drawings followed, some showing the dancers singly (3me Vente Degas, nos. 187, 188, 205, 206, 223, 253, 266 and 274) and then together (3me Vente Degas, nos. 190 [fig. 3], 225 and 237). Degas told his friend, the sculptor Paul-Albert Bartholomé, "It is essential to do the same subject over again, ten times, a hundred times" (quoted in exh. cat., p. cit., 1996, p. 258). He advised fellow painters to "Make a drawing, begin it again, trace it; begin it again, and retrace it" (ibid., p. 81). The reworked tracings and transfers generated vast extended families of related drawings, marking in Degas's work "the emergence of a new kind of seriality, analogous to some of the 'series' patterns of his peers, but technically unique to himself' (ibid., p. 71).

Having arrived at one or more preparatory drawings of the subject that pleased him, Degas traced them a final time, and had Père Lézin, a print specialist, framer and colleur, lay down the sheets of tracing paper on durable Bristol board. The artist purposely avoided the use of fine rag, hand-made and specially textured pastel papers. Degas would then proceed to work the images in pastel, first applying the powdery pigment in broad strokes using the side of the stick, and then utilizing the the tip to create a fine, unidirectional array of what the artist called his "zébrures" ("stripes"), resulting in a densely striated surface of colored lines. He would frequently apply a fixative, made from a unknown recipe given him by the painter Luigi Chialiva, to render each layer of pastel permanent, and allow for further applications and the progressive build-up of color. The layering of pastel generated both subtle hybrid tones and scintillating optical mixtures; Joris-Karl Huysmans noted Degas's ability to "invent neologisms of colourNo artist since Delacroix has understood like M. Degas the marriage and adultery of colours" (quoted in ibid., p. 100).

Some studies were relatively lightly drawn, with minimal layering (Lemoisne, no. 1243; fig. 4), but nearly all are entirely satisfying in the state the artist ceased working on them. The closest siblings in pastel to Danseuses are Deux danseuses en bleu et rose (Lemoisne, no. 1241), and of the right hand figure only, Danseuse rose (Lemoisne, no. 1242). One might designate as cousins by varying degrees those pastels which show the present image reversed (Lemoisne, no. 1367; fig. 5), or reversed and enlarged (Lemoisne, no. 1323; fig. 6). DeVonyer and Kendall have written: "Degas must have thrilled to the sense that this process of repetition and variation so visibly rhymed with the dancing practices it depicted, and that both drawing and ballet exploited the mirroring of actions and the progression from spare, colorless exercises to multi-hued brilliance Color allowed him to manufacture variation after variation on single scenetwinned works were never left as an identical pair, but typically cropped and extended, their details suppressed or their characters modified as he contrived new pictorial identities for each emerging composition By repeating his subjects, Degas seemed to deepen the game he had created, pursuing new expressive permutations that had previously been beyond his self-imposed brief" (exh. cat., op. cit., 2002, pp. 258 and 260).

The large number of drawings and pastels that employ the pose seen in Danseuses attests to Degas's persistent interest in the interaction between these two girls. One aspect of this engagement, as Degas stated, was that they provided him a pretext to draw, to explore ways of seeing and rendering form. Tracking the formal design within this close-up and tightly cropped composition reveals a serpentine arabesque that arises from the open trapezoid of the right-hand dancer's splayed legs, and dovetails with a similar form outlined by the the bent arm and cut-off foot of the left-hand figure. Degas reiterated the narrow V-shape of the merging arm and leg near the center of the composition in the jutting elbow at upper left. This twisting armature of limbs lends shape and movement to the diaphanous veils of color; the narrow shadows create the effect of a shallow relief, as in the Greek friezes Degas studied in the Louvre.

There is a human element here as well. Degas has underscored a sense of intimacy by calling attention to the sympathetic relationship between the two dancers, even if he has given us hardly any indication of their individual expressions and personalities. The overall effect is anonymous, monumental, and timeless; while the dancers seem weary and nearly spent from their endeavors, the composition suggests an underlying resilience, a deeper well of energy held in reserve. The connection between Degas and the dance now comes into focus. Despite differences in age, gender and class, Degas observed in the difficult and all-consuming regimen that these young women practiced a metaphor for process in his own calling, for the aims and ideals he held forth in his art. Degas wrote in one of his sonnets (from R. Gordon and A. Forge, Degas, New York, 1988, p. 201; trans. Richard Howard):

...Those who grasp the mystery

of bodies moving, eloquent and still,

Who see--who must see in the fleeting girls

all trace vanish of their transitory soul,

Flashing faster than the finest strophe;

--All, even the crayon's careful grace:

A dancer has All, though weary as Atalanta:

Serene the tradition, sealed to the profane.

Vétheuil, effet de soleil by Claude Monet

Rounding out the exceptional offerings of Impressionist works in the sale is Monet's Vétheuil, effet de soleil. This sun-drenched view of the picturesque village of Vétheuil was painted in 1901, when Monet was refining the distinctive serial approach that would yield some of his most celebrated late career works, including the water garden paintings at Giverny. All fifteen of the Vétheuil paintings, including the present work, take in the same view from across the Seine, varying only in lighting effects and weather conditions. "Vétheuil, effet de soleil" was one of a number of works from the series that was purchased by Galerie Durand-Ruel in 1902, where it remained until its sale to a private collector in 1949. Seven of the 15 views in the Vétheuil series are now housed in major museum collections around the world, including the Musée D'Orsay and the Pushkin Museum.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) Vétheuil, effet de soleil, signed and dated 'Claude Monet 1901' (lower left) oil on canvas, 32¼ x 36 5/8 in., (82 x 93 cm.) Painted in 1901. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Provenance: Galerie Bernheim-Jeune et Cie., Paris (acquired from the artist, February 1902).

Galerie Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris (acquired from the above, 28 October 1902).

Galerie Durand-Ruel et Cie., New York (aquired from the above, 19 November 1902 and until 1949).

Private collection.

Literature: G. Riat, "Petites expositions," La Chronique des Arts, 22 February 1902, p. 59.

A. Alexandre, "La vie artistique. II. Exposition Monet-Pissarro," Le Figaro, 27 February 1902, p. 5.

C. Saunier, "Gazette d'Art. Monet, Pissarro...," La Revue blanche, March 1902, pp. 385-386.

E. Pilon, "Carnet des oeuvres et des hommes. Plusieurs paysagistes," La Plume, 15 March 1902, pp. 411-413.

T. Duret, "Cl. Monet und der Impressionismus," Kunst und Künstler, March 1904, p. 242 (illustrated).

L. Venturi, Les Archives de l'Impressionnisme, Paris, 1939, vol. I, p. 378.

D. Wildenstein, Claude Monet, biographie et catalogue raisonné, Lausanne, 1985, vol. IV, p. 198 (illustrated, p. 199).

D. Wildenstein, Monet, Catalogue raisonné, Cologne, 1996, vol. IV, p. 737, no. 1638 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Paris, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune et Cie., Pissarro-Monet, 1902.

Minneapolis, Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, A Special Exhibition of Paintings by the French Impressionists and of the Works of Six American Artists Residing in Paris, April-May 1908, p. 14, no. 39. (possibly) New York, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paintings of different periods by Monet, February 1911, no. 6-18.

New York, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet, March 1940, no. 7.

Notes: This sun-drenched canvas is one in an important series of fifteen paintings that Monet executed during the summer and early autumn of 1901, showing the picturesque village of Vétheuil on the right bank of the Seine (Wildenstein, nos. 1635-1649). The artist had lived and worked at Vétheuil from 1878 to 1881, a watershed moment in his career, and his later views of the town may be understood in part as a nostalgic return to a motif which held deep personal and artistic resonance for him. At the same time, the 1901 paintings of Vétheuil are significant examples of the distinctive serial approach that Monet had come to practice, in which virtually identical views of the motif vary only in their lighting effects and weather conditions. The Vétheuil pictures reveal the same fascination with the evanescent aspects of nature that characterize such celebrated late series as those Monet painted of his water garden at Giverny and of the Thames River in London. Discussing the significance of this period in Monet's oeuvre, Paul Tucker has written: "Between 1900 and his death in 1926, Monet produced some of the most novel paintings of his career...that today are justifiably hailed as landmarks of late Impressionism. Filled with beauty, daring, and bravura, they stand as eloquent witness to an aging artist's irrepressible urge to express his feelings in front of nature. They also attest to his persistent desire to reinvent the look of landscape and to leave a legacy of significance" (in Monet in the 20th Century, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1998, p. 14).

Even at the outset of the new century, Vétheuil remained an idyllic, agrarian hamlet of only a few hundred inhabitants. Situated 37 miles (60 km.) northwest of Paris, the town stands on a hill overlooking a gentle bend in the Seine. Vétheuil's major landmark is the Romanesque church of Notre-Dame, which occupies a commanding position in the heart of the community (fig. 1). With neither a bridge nor a rail station, and only minimal industry, Vétheuil showed little evidence of the encroaching modernity that had become endemic elsewhere in the region. Shortly after settling there in 1878, the artist described the town in a letter to Eugène Maurer as "a ravishing spot from which I should be able to extract some things that aren't bad" (quoted in M. Clarke and R. Thomson, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, 1878-1883, exh. cat., National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2003, p. 17).

Monet's fifteen views of Vétheuil from 1901 were all painted from Lavacourt, a small village on the opposite bank of the Seine. In July, frustrated by the stifling heat in his studio at Giverny, and unable to work in his water garden because of renovations, Monet began to have his chauffeur drive him and his wife Alice to Lavacourt in the afternoons, a distance of less than 8 miles (12 km.) that was easily traversed in the family's new Panhard-Levassor motor car. By the end of the month, the artist had rented a modest house at Lavacourt with a second-floor balcony and an excellent view across the river to Vétheuil. Pleased by this motif, he painted there nearly every day until October, when he wrote to Durand-Ruel, "I have undertaken a series of views of Vétheuil that I thought I would be able to finish quickly and which have taken me all summer" (quoted in ibid., p. 52). Once given the opportunity to view the completed paintings, the artist's dealers quickly realized their commercial potential. During the first three months of 1902, Monet sold eight canvases to Bernheim-Jeune--some of which were later acquired by Durand-Ruel (including the present picture)--and two to Boussod, Valadon et Cie., netting the artist a total of 80,000 francs--enough to cover the cost of the ongoing work on his gardens and to pay for the Panhard-Levassor several times over.

The fifteen Vétheuil paintings were all executed from precisely the same viewpoint, on canvases that were either square, or nearly square, in format. The village itself is pressed into the upper third of the canvas, with the larger lower section given over to the expanse of the Seine. The church of Notre-Dame forms the focal point of the pyramidal composition, rising proudly and protectively over the town's quaint cluster of whitewashed houses. In the present canvas, a stiff breeze ripples the surface of the water, breaking up the reflections of the town that appear prominently in some of the companion pictures. The water shimmers in the sunlight; the landscape is suffused in the golden, late afternoon light of a summer's day. In other pictures of this series, Monet rendered Vétheuil earlier in the afternoon (fig. 2) or the rosy glow of sunset (fig. 3). Discussing this group of paintings, John House concludes, "For Monet, the distinctive quality of the site lay in what he called the enveloppe--its distinctive light and atmosphere" (in op. cit., exh. cat., Boston, 1998, p. 9).

Monet had painted several similar views of Vétheuil when he lived there in the late 1870s. Particularly close in composition are four great landscapes which Monet executed during 1879 in a somewhat wider format (W. 531-534; fig. 4). Although Monet's handling in the 1901 canvases is much freer and less detailed, the motif is nearly identical in the two series. Paul Tucker has written, "These paintings were unabashed retreats to pictures he had done of the same site during his stay in Vétheuil more than two decades earlier, and were suffused with sweet nostalgia for the time he had spent in that village some twenty years earlier" (op. cit., p. 39). Andrew Forge has suggested a more specific reason for Monet's renewed exploration of Vétheuil in 1901. His stepdaughter Suzanne had just died, and both he and Alice were in deep mourning. "There must have been some connection between this sadness and his return to Vétheuil, the place where [his first wife] Camille had died and where he and Alice had started their lives together some twenty years before. In these canvases, personal memories and memories of work were interwoven" (in Monet, Chicago, 1995, p. 60).

Vétheuil indeed held artistic as well as personal significance for Monet in 1901. The years that he spent there between 1878 and 1881 marked a key juncture in his work--"a decisive moment of personal and artistic reassessment...[and] the most momentous change in the career of the most revolutionary Impressionist" (C. Stuckey et al., Monet at Vétheuil: The Turning Point, exh. cat., University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, 1998, pp. 13 and 41). Following his move to Vétheuil, Monet entirely abandoned the contemporary themes that had dominated his earlier work and he began to focus instead on the description of fugitive aspects of nature seen in changing light. This nascent serial technique laid the groundwork for Monet's most important later production. By 1901, Monet was hard at work on two of the most challenging and innovative serial undertakings of his career: the water garden and the Thames. His return to Vétheuil at this time may represent an effort to re-engage with the site of the earliest experiments in his distinctive and innovative mode of rendering the landscape.

More generally, the 1901 paintings of Vétheuil reflect Monet's mounting interest in the latter years of his career in reworking themes from his own previous painting. His views of the beaches and cliffs at Pourville from 1896-1897, for instance, constitute a renewed exploration of motifs that had occupied him during the early 1880s, while the Thames series of 1899-1901 was the fulfillment of a long-cherished plan to revisit sites that he had painted in 1871 while living in London. As the artist told François Thiébault-Sisson around the turn of the century, "Ever since I turned sixty, I have had the idea of undertaking, for each of the types of motif which had in turn shared my attention, a sort of synthesis in which I would sum up in one canvas, sometimes two, my past impressions and sensations. I would have to travel a great deal and for a long time, to revisit one by one the staging posts of my life as a painter and to verify my past feelings" (quoted in J. House, Monet: Nature into Art, New Haven, 1986, p. 31).

Seven of the fifteen views that Monet painted of Vétheuil in 1901 are now housed in major museum collections: the Pushkin Museum (W. 1635), the Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal (W. 1641), the Art Institute of Chicago (W. 1643 and 1645), the Musée d'Orsay (W. 1644), the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille (W. 1646), and the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (W. 1648).

Modern Highlights

Two magnificent Modern works not seen in public for over four decades are offered from the estate of Jack J. Dreyfus, Jr., founder of the highly successful brokerage firm Dreyfus & Co. Rosace by Henri Matisse is a paper cut-out in the form of a symmetrical, stylized rose that served as the marquette for a stained glass window commissioned in memory of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller for the Union Church in Pocantico Hills, NY. The massive, seven-foot wide design is a perfect illustration of the innovative paper cut-out process that was Matisse’s creative passion during his last years. Sadly, Rosace would become Matisse's own swan song. On the day he wrote a letter confirming the completion of the marquette, Mattisse suffered a stroke and died just two days later. After his death, the gouache, pencil and paper collage was laid down on canvas to be preserved for prosperity.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) Rosace; gouache, pencil and paper collage on paper laid down on canvas. Diameter: 76 in. (193 cm.) Executed in 1954. Est. $3,000,000 - $4,000,000. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Also from the Dreyfus Estate is Wassily Kandinsky's "Winkelschwung" (“Angular Swing”) from 1929 (estimate: $1.5-2.5 million), a vibrant work that bears the influence of the artist's teaching residency at the legendary Bauhaus. Populated with geometric shapes, lines, and points arrayed along an obtuse angle, the painting may be read as a landscape of buildings and tree forms, or as an interpretation of the Bauhaus campus itself.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) Winkelschwung, signed with monogram and dated '29' (lower left); signed with monogram and dated again, numbered and titled 'No 473 1929 "Winkelschwung"' (on the reverse) oil on board, 19 1/8 x 27 5/8 in. (48.5 x 70 cm.) Painted in 1929. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Composition II, with Red, 1926 by Piet Mondrian

"Composition II, with Red", 1926 by Piet Mondrian is a highly minimal painting from a pivotal year in the artist’s career during which he broke with the de Stijl movement and embraced his own individualistic style. Consisting solely of four straight lines and one primary color on a white background, Composition II, with Red is from an important group of four paintings often referred to as the “Dresden Paintings”. The only other work from this outstanding group that is still known to exist is "Composition IV, with Red", now in the permanent collection of the Kaiser Welhelm Museum in Krefeld.

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) Composition II, with Red, 1926, signed with initials and dated 'PM 26' (lower left) oil on canvas, 19¾ x 20 1/8 in. (50.2 x 51.1 cm.) Painted in 1926. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Provenance: The artist's estate, 1944-1960.

Harry Holtzman, New York (acquired from the above).

Sidney Janis Gallery, New York.

Edgar J. Kaufmann, Jr., New York (acquired from the above, 1960); sale, Sotheby's, New York, 15 November 1989, lot 13.

Private collection, Europe; sale, Christie's, London, 22 June 2004, lot 30.

Acquired from the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: "Black is Right," Town & Country 99, June 1944, issue 64-67, p. 64, no. 4261 (illustrated).

M. Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Life and Work, New York, 1956, p. 273, no. 152 (illustrated).

C. Greenberg, "Modernist Painting," Art and Culture Essays, Boston, 1961, p. 106 (illustrated).

C.L. Ragghianti, Mondrian e l'arte del XX secolo, Milan, 1962, pp. 332, 338 and 375 (illustrated, p. 306).

F. Elgar, Mondrian, New York and Washington, 1968, p. 131, no. 121 (illustrated).

M.G. Ottolenghi, L'opera completa di Mondrian, Milan, 1974, p. 111, no. 367.

N.J. Troy, "Correspondence between Katherine S. Dreier and Piet Mondrian," Mondrian and Neo-Plasticism in America, New Haven, 1979, p. 61.

H. Holtzmann and M. James, eds., The New Art, The New Life, The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian, Boston, 1986, no. 170 (illustrated).

J.M. Joosten and R.P. Welsh, Piet Mondrian, Catalogue raisonné, Antwerp, 1988, vol. II, 1911-1944, p. 322, no. B170 (illustrated).

Exhibited: Dresden, Kunstausstellung Kühl, 1926 (titled 'Dresden II').

Mannheim, Städtische Kunsthalle, Wege und Richtungen der Abstrakten Malerei in Europe, January-March 1927, no. 253 (titled 'Komposition III').

(Possibly) Frankfurt, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Der Stuhl, March 1929.

New York, Museum of Modern Art, Piet Mondrian, March-May 1945, no. 27 (titled 'Composition in White and Red').

New York, Valentine Gallery, Mondrian, Paintings, March 1946, no. 7 (titled 'Composition. Noir, Blanc, Rouge').

New York, Sidney Janis Gallery, Piet Mondrian, February-March 1951, no. 23 (titled 'Composition').

New York, Sidney Janis Gallery, 50 Years of Mondrian, November 1953, no. 27 (titled 'Square Composition').

New York, Sidney Janis Gallery, Examples of the classic phase of Arp & Mondrian in Painting, Sculpture and Relief, January-March 1960, no. 25 (titled 'Composition in a Square').

Notes: Painted on a 50 centimeter square canvas, consisting solely of four straight lines and one primary color on a white background, Composition II, with Red is an important and highly minimal work painted by Mondrian in Paris in 1926. As Michel Seuphor has recalled of this time, "the year 1926 was important in Mondrian's life," marking a turning point for the artist which signaled the end of his association with the de Stijl movement and the beginning of a new and more independent identity. It was possibly a consequence of Mondrian's break with Van Doesburg in 1925, that his paintings of 1926 are distinguished by an ever-increasing reductivism in which the artist pared down even further the sparse pictorial logic, the "neo-plasticism" of his paintings to their barest essentials. As Composition II, with Red demonstrates, it was indeed possible to considerably reduce the basic elements of de Stijl and still maintain the integrity of the "neo-plastic" aesthetic.

Composition II, with Red is one of an important group of four paintings often known as the "Dresden paintings." Painted in 1926, they were sent the following year on consignment to the Kunstaustellung Kühl in Dresden. Only the present work (also known as Dresden II) and Composition IV, with Red or (Dresden IV, fig. 3), now in the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum in Krefeld, are still known to exist. Mondrian, who lived in a state of near poverty for much of the early 1920s and was often compelled to paint naturalistic flower-paintings for money during this period so as to fund his less saleable abstract work, had recently begun to find patrons of his work in Dresden. In 1926 Mondrian had been commissioned to design a library-study for an Ida Bienert living in Dresden. At the same time a diamond composition of his, Tableau no. 1 (1925), had also been bought from the Kunstaustellung Kühl by the dancer Gret Palucca who, to Mondrian's delight, had hung the work at a specific place on the large empty wall of her dance studio "as a point of rest for when she takes a break" (letter from Piet Mondrian to J.J.P. Oud cited in Piet Mondrian, exh. cat., MoMA, New York, 1995, p. 221).

These commercial successes in Dresden were welcomed by Mondrian not just for the much-needed income they brought but also that they seemed to reflect the public's growing understanding of his work as a bridge between art and architecture. Mondrian saw his paintings not as mere objects but as architectural statements that posited new ideas about the nature of form and space that could and, he hoped one day would, be integrated into the structure of the life of "future man." As a response to his quest for an absolute, for Mondrian his painting had to both respond to and interact with the modern environment in which it was created. In this respect, of course, most importantly, art had to respond to the metropolis. "The truly modern artist," he wrote, "sees the metropolis as a formal equivalent of abstract life; it is closer to him than nature and gives him a stronger feeling of beauty. For, in the big city, nature has already been constrained and ordered by the human spirit. The proportions and rhythms of architectural surfaces and lines speak more directly to the artist than do the whims of nature; henceforth, the big city is where the artistic-mathematical temperament of the future will develop, the place from which the New Style will emerge" (cited in Serge Lemoine, Mondrian and de Stijl, London, 1987, p. 30).

In accordance with these sentiments, Mondrian saw his paintings as working towards the end of easel painting. The formal and spatial principles they extolled should, he believed, be extended beyond the picture frame into life. To this end he himself put these principles into practice in the arrangement of his own living space. In his studio at 26 Rue du Départ in Paris he covered the white walls with colored cardboard shapes arranged like his paintings in accordance with Neo-plastic principles. He painted all the objects in the studio--the few pieces of furniture he had and his treasured gramophone player--in primary colours in order to create what he described as "a new design for living." In order to further propagate this utopian message of his art as a blueprint for the future, he had a series of photographs taken of this studio which he published in 1926. Forming the centerpiece of one of these photographs is a now lost work that bears a very close resemblance to Composition II, with Red. A complete and persuasive integration of his painted work into its environment, this photograph is a powerful illustration of the way in which Mondrian believed the principles of his art could be extended into life. It is a pictorial manifesto of his belief in the total work of art.

Composition II, with Red is a deceptively simple work that represents a cornerstone of Mondrian's art. Reduced to the most simple and essential of elements, its harmoniously resolved composition creates a tension and dynamism with only the barest of means. In this it articulates the principles of Neo-Plasticism which, with the help of Seuphor, Mondrian had painstakingly translated into manifesto form in 1926, exhibiting all the non-symmetrical balance between form and space and between the notion of "mind and material" that Mondrian had here demanded of art. "Balance through the equivalence of nature and mind, of that which is individual and that which is universal, of the feminine and the masculine--this general principle of Neo-Plasticism can be achieved not only in plastic art, but also in man and society," Mondrian had asserted. "In society, the equivalence of what relates to matter and of what relates to mind can create a harmony beyond anything hitherto known" ("The General Principles of Neo-Plasticism," 1926, cited in M. Seuphor, Mondrian. Life and Work, London, 1956, p. 168). In reducing the language of his art to its finest point, Mondrian was also fiercely demonstrating the power of the painterly system he had devised to articulate form and space. He did this however not out of a sense of personal pride but out of a sense of mission. "To be concerned exclusively with relations, while creating them and seeking their equilibrium in art and life, that is the good work of today, that is to prepare the future" (ibid.).

Sculpture Highlights

Few 19th century sculptures are more instantly recognizable than Rodin's "Le Baiser" (The Kiss), a romantic depiction of an embracing couple inspired by a tale of forbidden love from Dante's Inferno. Christie's is pleased to offer an extremely rare bronze cast of the sculpture, one of only five created during the artist's lifetime from the plaster model of the sculpture known as the Milwaukee version. In these versions only, the male figure's right hand is lifted slightly from the thigh of his lover so that it appears to hover tentatively, a poignant gesture that Rodin called "more respectful". Owned by Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge until 1975, this elegant, 34-inch tall bronze has been in a private collection in New York for nearly 35 years.

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) Le Baiser, moyen modèle dit "Taille de la Porte" (modèle avec base simplifiée) signed 'Rodin' (on the back of the base) bronze with brown patina. Height: 34 in. (86.4 cm.). Conceived in 1880-1881 and cast between 1887-1901. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Rounding out the sculptural highlights in the sale are Alberto Giacometti's Femme Debout, (estimate: $1.4-1.8 million) from a series of thin, elongated standing female figures the artist conceived in 1960- 61; Edgar Degas' "Grand Arabesque" (estimate: $500,000-700,000), an elegant bronze of a young female dancer in mid pose, extending her body from fingertips to toes; and Rodin's "Néréides" (estimate: $200,000-300,000), a depiction in bronze of three intertwined sea nymphs.

Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) Femme debout, signed and numbered 'Alberto Giacometti 6/8' (on the right side of the base); inscribed with foundry mark 'Susse Fondeur Paris' (on the back of the base) bronze with green and brown patina. Height: 17¾ in. (45.1 cm.) Conceived in 1961 and cast in 1993. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) Grande arabesque, troisième temps, stamped with signature, numbered and stamped with foundry mark 'Degas 16/J CIRE PERDUE A.A. HÉBRARD' (on the top of the base) bronze with brown patina. Height: 15 1/8 in (38.4 cm.) Original model executed circa 1882-1895; this bronze version cast in an edition of twenty-two, numbered A to T plus two casts reserved for the Degas heirs and the founder Hébrard. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) Néréides, grand modèle dit aussi "Trois Sirènes" ou "La Vague", signed 'Rodin' (on the front of the base); inscribed with foundry mark 'L. Perzinka Fondeur Versailles' (on the back of the base) bronze with brown patina. Height: 17 in. (43.2 cm.) Length: 17½ in. (44.5 cm.) Conceived in 1887 and cast in 1899. Photo Image 2009 Christies Ltd

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F57%2F119589%2F64370738_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F36%2F03%2F119589%2F64361206_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F92%2F119589%2F61703506_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F00%2F119589%2F61670151_p.jpg)