"Tracing the Past, Drawing the Future: Master Ink Painters in 20th-Century China" @ Cantor Arts Center

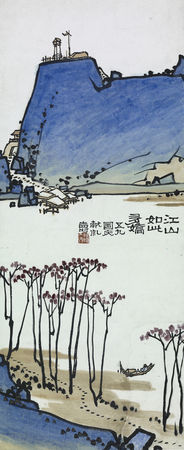

Pan Tianshou (China, 1897–1971), This Land So Beautiful, 1959. Hanging scroll, ink and color. Lent by the Pan Tianshou Memorial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Stanford, California —— Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University announces an exhibition that brings to the United States a rare and important group of 20th-century paintings by four Chinese modern masters. The exhibition “Tracing the Past, Drawing the Future: Master Ink Painters in 20th-Century China” presents more than 110 works, in two rotations, February 17 through July 4, 2010. Admission is free.

“This landmark exhibition illuminates a turning point in the development of Chinese ink painting during the 20th-century,” explained Dr. Xiaoneng Yang, the Cantor Arts Center’s Patrick J. J. Maveety Curator of Asian Art. “Drawing upon paintings and calligraphy on loan from Chinese collections new to American audiences, the exhibition presents monumental portraits, vibrant bird-and-flower painting, and spectacular landscapes by Wu Changshuo (1844–1927), Qi Baishi (1864–1957), Huang Binhong (1865–1955), and Pan Tianshou (1897–1971). Collectively known in China as the ‘Four Great Masters of Ink Painting,’ these artists faced the dual challenges of negotiating the impact of encounters with the West, while inventing new directions for long-held practices of ink painting.”

A fully illustrated catalogue with scholarly essays in English accompanies the exhibition, including two introductory essays and essays on each artist. Full entries, translated from Chinese, accompany images of the works in the exhibition.

An international symposium, "The Politics of Culture and the Arts in Early 20th-Century China" will be held February 19–21. Cosponsored by Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, Center for East Asian Studies, and Department of Art and Art History, the symposium is open free to scholars and the public.

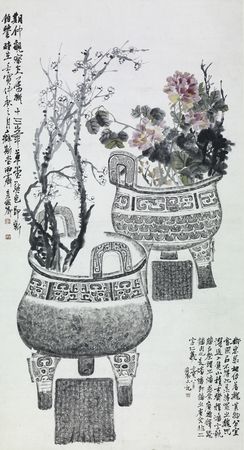

Wú Chāngshuò (吳昌碩) (September 12, 1844 - November 29, 1927). Born in Anji Zhejiang Province, Wu Changshuo (1844-1927) was a central figure in Chinese painting during the early years of the 20th century. Wu was born into a family of scholarsunder which was forced to flee the violence and the turmoil inflicted by the infamous Taiping rebellion. Wu was eventually separated from his family and thereafter dedicated himself to art and different facets of traditional culture, mainly to the art of calligraphy and traditional seal carving. His seals became famous for their elegance and soon became an independent style known as the "Wu style". Wu became the first director of the Xiling Seal Carving Society and at the same time made a living from selling his calligraphy which was a peculiar blend of many different scripts.

Wú Chāngshuò (吳昌碩) (September 12, 1844 - November 29, 1927). Born in Anji Zhejiang Province, Wu Changshuo (1844-1927) was a central figure in Chinese painting during the early years of the 20th century. Wu was born into a family of scholarsunder which was forced to flee the violence and the turmoil inflicted by the infamous Taiping rebellion. Wu was eventually separated from his family and thereafter dedicated himself to art and different facets of traditional culture, mainly to the art of calligraphy and traditional seal carving. His seals became famous for their elegance and soon became an independent style known as the "Wu style". Wu became the first director of the Xiling Seal Carving Society and at the same time made a living from selling his calligraphy which was a peculiar blend of many different scripts.

Wu Changshuo influenced a later trend in painting that belonged to a Chinese artistic movement known as Hai Pai or Shanghai School.This highly influential cultural trend became dominant in painting as well as in cinema, music and literature. The Shanghai School had a romantic character and stressed the idea of "art for art's sake", it combined eastern and western aesthetics and reflected the great changes that cities such as Shanghai were going through. Wu started painting rather late during his thirties and he was fully able to express his diverse skills and talent. His bold and vigorous brushstrokes never crossed the line of becoming too grotesque, thus although powerful they still showed control, gentleness and refinement. Wu liked to use sharp contrast between light and dark and was a forerunner in the use a red color introduced from the west called "Western Red" or "Yang Hong". In his plum blossom paintings which he is most famous for Wu replaced the small and meticulous strokes of the time with large and bold strokes derived from calligraphy together with the "Western Red" to create something that was very fresh, full of vitality and obviously different to the trained eye of the Chinese who were familiar with the long tradition of Plum blossom painting. Wu Changshuo's art displayed great mastery of brush and ink he was largely responsible for rejuvenating the genre of Flower-and-bird painting by introducing an expressive, individualistic style more generally associated with the literati School of painting, his art inspired his contemporaries as well as later generations, his art had influence over great painters such as Qi baishi and Pan Tianshou. (arts.cultural-china.com)

Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) “Tripod Ding Cauldrons,” 1902. Hanging Scroll. Ink and colors on paper. 70.9 x 37.99 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) “Pigeonberry,” 1917. Hanging Scroll. Ink and colors on paper. 67.4 x 17.7 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) “Chinese Tree Peony and Running Script”. Folding fan, 1907. Ink and colors on paper, lacquer. 7.13 x 19.33 inches. Hangzhou History Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Qi Baishi ( 齊白石) (January 1, 1864 - September 16, 1957) was born in 1863 in Xiangtan County, Hunan Province. In his early youth he was trained as a woodcarver and soon became a master in this discipline. Later he turned to painting, poetry, calligraphy and seal carving.

Qi Baishi ( 齊白石) (January 1, 1864 - September 16, 1957) was born in 1863 in Xiangtan County, Hunan Province. In his early youth he was trained as a woodcarver and soon became a master in this discipline. Later he turned to painting, poetry, calligraphy and seal carving.

Starting to paint at a rather late age, Qi was compelled to experiment with new forms of art. He obsessively copied different features and motifs from the famous Qing Dynasty painting manual The Mustard Seed Garden. Qi experimented with many different forms and styles of painting both from China and the West. Under the strong influence of Xu Wei, Bada Shanren and Wu Changshuo, he slowly started to develop a unique and more modern style of his own. Like the masters of the Qing who stressed the importance of subjective expression and a strong sense of individuality, Qi took this Xie Yi style, namely, painting ones feelings and mood rather than painting realistically, to new heights. Like the great masters which influenced his art, Qi Baishi's style and technique is classified as Da Xieyi, or 'Big' Xieyi. As opposed to the 'Small' Xieyi style here the artist uses large brushes and economy of line to capture the spirit of the subject with swift and vigorous strokes. Qi's paintings carry a strong sense of modernity and unique originality. Focusing mainly on flowers, birds, fish and insects, Qi gives his brush the kind of independence that very few artists dare to experiment with. His swift, sure, spontaneous brush strokes usually perfected only at an old age, turned Qi into China's most celebrated modern artist and indeed one of the worlds greatest painters. Qi Baishi is the Picasso of China. His simplicity, his forceful brush coupled with a strong sense of naivety and an almost child-like crudeness, combined to give the viewer some of the most powerful images in Chinese traditional art. In spite of his skills and complex compositions, Qi's art conveys a slightly awkward air which is the essence of his appeal. His most famous and attractive paintings were of shrimps and today one can refer to Qi's specific style of shrimp paintings as one can refer to Xu Beihong's horses, both artists gave these animals characteristic features that were immediately recognized by the Chinese as different and striking. Both artists had great influence over the evolotuion of modern Chinese art.

Qi's mature style emerged only in the 1920's after he moved to Beijing, he was only fully recognized at the old age of sixty but continued to create and produced his greatest masterpieces during his seventies and eighties. He died in Beijing on September 16, 1957 at the age of 94. (arts.cultural-china.com)

Qi Baishi (1864–1957) “Pine Grove and Hobbyhorse,” late 1920s. Hanging Scroll. Ink and color on paper. 55.51 x 19.09 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Qi Baishi (1864–1957) “Banyan Leaves and Autumn Cicadas,” (detail), 1923. Hanging Scroll. Ink and color on paper, 35.43 x 14.17 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Qi Baishi (1864–1957) “Couplet in Running Script,” 1922. Hanging Scroll. Ink on paper. 55.9 x 8.39 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Qi Baishi (1864–1957) “Seven-Character Couplet in Seal Script,” 1926. Hanging Scroll. Ink on paper. 68.9 x 9.25 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Huáng Bīnhóng (黃賓虹) (1865-1955) born in East China's Zhejiang Province in 1865. He was the grandson of artist Huang Fengliu. He began to study traditional landscape painting when he was 6 years old. In his youth, Huang traveled and spent many years teaching at art colleges in Shanghai, Beijing and Hangzhou. Hang Binhong came to Hangzhou in 1848 to be the professor of the National Arts Vocational School and later the Central Fine Arts Academy.

Huáng Bīnhóng (黃賓虹) (1865-1955) born in East China's Zhejiang Province in 1865. He was the grandson of artist Huang Fengliu. He began to study traditional landscape painting when he was 6 years old. In his youth, Huang traveled and spent many years teaching at art colleges in Shanghai, Beijing and Hangzhou. Hang Binhong came to Hangzhou in 1848 to be the professor of the National Arts Vocational School and later the Central Fine Arts Academy.

He is considered one of the last innovators in the literati style of painting and is noted for his freehand landscapes, was well versed in the works of the great masters of the past and followed many of their techniques. He experimented with traditional techniques in the use of ink, including shading and layering. He achieved a simple yet profound effect in his landscapes by the use of thick dark ink over which he applied light or heavy coloring. His landscape paintings featured 'black, dense, thick and heavy'. He applied ink layer by layer so that brightness could be seen through the density. Huang's work is known for its powerful brushwork and his fresh approach to composition, incorporated fresh ideas into traditional Chinese painting. He was the modern embodiment of the literati ideal. Huang and his contemporary Qi Baishi became known by the sobriquets Huang of the South and Qi of the North.

He was also an art theorist and art historian, who He wrote down his theories in books like Origins Of Yellow Mountain Painters, Talks About Paintings, An Outline Of Chinese Paintings and A Survey Of Ancient Seals.

This documentary represents Mr. Huang Binhong's abundant life of art study and development, and largely displays his famous paintings and styles in different periods. (arts.cultural-china.com)

Huang Binhong (1865–1955) “Discourse on Tang Blue-and-Green Painting, “1952. Hanging Scroll. Ink and colors on paper. 39.88 x 16.85 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Huang Binhong (1865–1955) “Sketches of Drawings Done from Life while in South China,” 1940s. Ink and colors on paper. 19 pages at 7.6 x 21.06 inches each. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

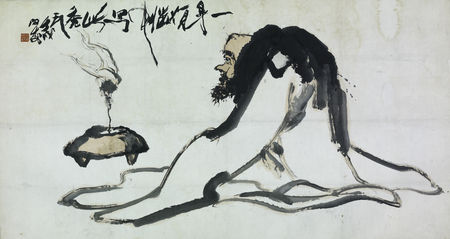

Pan Tianshou (潘天寿) (1897-1971), Chinese painter, art educator, and art theorist who was one of the most important traditional Chinese painters of the 20th century, following Wu Changshuo, Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong, promoted the development of Chinese painting.

Pan Tianshou (潘天寿) (1897-1971), Chinese painter, art educator, and art theorist who was one of the most important traditional Chinese painters of the 20th century, following Wu Changshuo, Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong, promoted the development of Chinese painting.

Pan was born into a peasant family in Ninghai County, Zhejiang Province in 1807. His parents gave him the name Tianshou (meaning endowed by the heaven, later changed to Tianshou meaning live as long as the heaven). His styled name was Dayi, alias Ashou, but he often used Leipuotoufeng Shouzhe when he signed his later works. Pan's family lived in a direly poor situation since he was young, but he deeply loved calligraphy and painting. Through self-teaching, he learned the art of painting by imitating the works of Xu Wei, Zhu Da and Shi Tao. Later, he took democratic educators Li Shutong, Jing Hengyi, etc., as his teachers. In 1923, he and Mr. Zhu Wenyun established China's first department of Chinese paintings at the Shanghai School of Fine Arts. He later taught at the National School of Arts, the East China branch of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts. He was indisputably one of the principal founders in the teaching of modern Chinese painting. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, he served as the president of Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts and vice-president of Zhejiang Association of Artists. He died in 1971.

Pan Tianshou spent the better part of his life in painting and teaching of painting. He is good at freehand brushwork. His paintings on flowers, birds, mountains and waters have the style of the ancient masters like Xu Wei, Zhu Song and Shi Tao, as well as features of the modern artist Wu Changsuo. He is skilled in 'creating suspense' and 'breaking suspense' in the layout of his paintings. Radiating from his brushes is the splendor of gold and stone, profound and lofty. With appropriate use of different paints and colors, his painting as a whole exhibits innate strength. He tapped the artistic method of Chinese painting which emphasized lines to the most. With his unique appreciation and understanding on arts, he blazed new trails in the structure and composition of the Chinese painting, making his works full of inspiration and modern senses. Pan Tianshou establishes his own painting style. His works were a kind of compendium of traditional Chinese paintings blending poems, calligraphy, painting and seal. He is also good at painting people, and is expert in finger painting. Besides, he is also a theorist on the painting history and the art of painting and comes up with witty remarks from time to time. In the 'Essays on Painting in Tingtian Pavilion', he wrote 'A mountain loses its spirit without cloud, loses its peculiarity without stones, loses its elegance without trees, and loses its life without water', and 'In painting, one should concentrate the mind, and hold the breath: with concentration of the mind, serenity is maintained; with the breath held up, preciseness is attained. One should be as serene as an old monk in meditation, and be as precise as a silk worm in spitting silk. The spirit and real fun of painting are from nature and beyond the brushes and paints'. Many of his remarks were also included in works like 'History of Chinese Fine Arts', 'On Seal-carvings'.

Besides introducing Mr. Pan Tianshou's artistic life and the painting theory that develops a school of his own, this documentary uses a large space and lots of rare historical shots to show elegance romantic charm that the master draws a picture in his own hand, with visual languages, reveals his composition and drawing techniques of representative works. (arts.cultural-china.com)

Pan Tianshou (1897–1971) “Bald Monk,” 1922. Horizontal hanging scroll. Ink and colors on paper. 37.32 x 67.72 inches. Pan Tianshou Memorial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Pan Tianshou (1897–1971) “Ink Frogs” (detail), 1961. Handscroll. Ink and colors on paper. 6.82 x 4.17 inches. Pan Tianshou Memorial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

Huang Binhong (1865–1955) “Seven-Character Poetic Couplet in Large Seal Script,” 1953. Pair of Hanging Scrolls. Ink on paper. 57.1 x 13.8 inches. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. Courtesy of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univers

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F22%2F46%2F577050%2F42758367_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F49%2F93%2F119589%2F40486997_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F48%2F01%2F577050%2F51942098_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F20%2F577050%2F42257697_o.jpg)