Japanese Tigers in British Museum

Porcelain plate with design of tiger. From Arita, Japan, Edo period, AD 1650-1670s. Gift of Mr. Akihiko Shibata. Asia JA 1997.1-21.13. British Museum, London

The tiger and bamboo are often depicted together in Japanese art, symbolizing complementary aspects of strength. The tiger has aggressive strength, while the gentle bamboo will bend but not break. This beast with its wide eyes and long vigorously waving tail has a somewhat playful air.

Maruyama Okyo, Tigers Crossing a River, a six-panel folding screen. Japan. Around 1781-2. Height: 153.5 cm. Width: 352.8 cm. Purchased with the support of the Art Fund. Asia JA 2006.4-24.01. British Museum, London

The scene shown on this screen follows an ancient Chinese legend, which is a kind of mental puzzle. When a mother tiger crosses a river with her three young cubs she has to be careful not to leave a ferocious one alone with either of the other two. How does she do it? In this painting the ferocious cub is the one on the right bank.

Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-95) was the most influential painter of his generation. The Maruyama-Shijō school that he set up became the dominant new style in Kyoto and Osaka, and also spread to Edo (Tokyo). Ōkyo’s revolutionary style was based on the suggestion of space in a picture, learned from European perspective, coupled with a belief in ‘painting from life’ (shasei). He probably never saw a live tiger, but instead worked from imported Chinese paintings and tiger skins. This may explain why his tigers often seem so cat-like.

Experts generally agree that Ōkyo was probably assisted in this painting by senior pupils, notably Gen Ki (1747-97). There are no other gold-leaf screen paintings of tigers by Ōkyo from his mature period currently known, making this work particularly significant. It was formerly in the collection of silk trader, Hara Sankei (1868-1939).

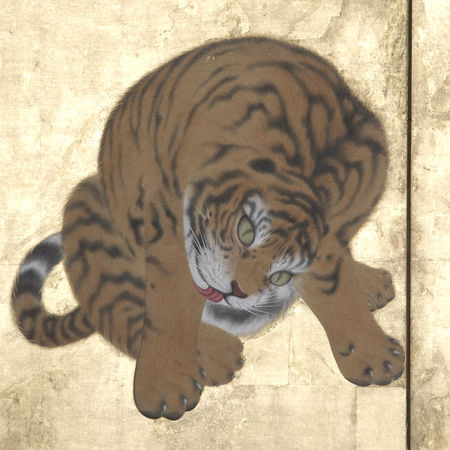

Hara Zaichū, 'The tiger roars and the wind blows', hanging scroll painting. Japan. Edo period, AD 1775. Height: 1170.000 mm. Width: 475.000 mm. Asia JA JP ADD1100 (1997.6-10.01). British Museum, London

A tiger stands tensed on a steeply sloping mountainside. The base of a pine tree juts out from the slope, and its branches protrude back into the picture above the animal's head. The work is probably copied from a Chinese prototype of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), but displays characteristic Japanese dynamism. In the early part of his career Zaichū (1750-1837) was famous for producing works based on Chinese models. Dates in Japan until 1873 ran in a sixty-year repeating cycle, and the date on this work corresponds to either 1775 or 1835, but the form of the signature and, in particular, the seals suggest the earlier date.

Zaichū was taught by the famous and highly influential Maruyama ōkyo (1733-95), but he broke away from his teacher's style to found his own school, lying somewhere between the orthodox Kanō, Chinese

The painting is inscribed 'Koshō fūsei' ('The tiger roars and the wind blows') and is signed 'Kinoto hitsuji fuyu Hara Chien ga' ('Painting by Hara Chien, winter of 1775'). The seals read 'Hara Chien in' ('Seal of Hara Chien') and 'Shichō'. Chien and Shichō were both art-names of Zaichū.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F54%2F28%2F577050%2F66207373_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F38%2F35%2F577050%2F66167687_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F77%2F577050%2F66151319_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F71%2F09%2F119589%2F66118115_p.jpg)