The Robert H. Blumenfield Collection to Be Offered at Christie's Asian Art Week

A finely carved botanical rhinoceros horn cup 17th/18th century. Carved in relief around the sides with a butterfly flitting amongst various plants and bamboo growing amidst rockwork, 5.1/4 in. (13.5 cm.) long. Estimate: $60,000-80,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

NEW YORK, NY.- On March 25, Christie’s New York will present For the Enjoyment of Scholars: Selections from the Robert H. Blumenfield Collection, a single-owner sale of exceptional Chinese carvings and works of art. Meticulously acquired over the past thirty years, the Blumenfield Collection is one of the most significant collections of Chinese scholar’s objects assembled. This extraordinary group of 158 objects includes rare and important examples from the 15th to the 19th centuries, offering a comprehensive range of rhinoceros horn and ivory carvings, works of art, ceramics and paintings that were appreciated and treasured by China’s scholarly elite.

“It is a great privilege to offer Selections from the Robert H. Blumenfield Collection, which is regarded as one of the most important collections of scholar’s objects in the United States. It is truly exceptional to find so many exquisite carvings and works of art in a single collection. The pieces that will be offered reflect the refined eye and elegant taste of a true connoisseur,” said Tina Zonars, International Director of Chinese Art.

Robert H. Blumenfield

Distinguished collector, scholar and author, Robert H. Blumenfield has dedicated his life to the study and appreciation of Asian Art. Over the past 30 years, Mr. Blumenfield has amassed a personal collection that reflects his discerning and distinctive eye. Each object has been chosen for its rarity and superb quality; many of the pieces are unique and exemplify the scholar’s idyllic pursuits.

Selections from the Robert H. Blumenfield Collection

Rhinoceros Horn carvings

Long prized for medicinal and mystical powers, rhinoceros horn was extremely precious and expensive to obtain, making carvings such as those presented in this collection difficult to acquire and rare to commission. Examples surviving to the present day are considered extremely scarce and highly sought-after. Collectors will have a unique opportunity to acquire top examples of this rare art form which is highly regarded for both its craftsmanship as well as its treasured material.

Among the rich repertoire of subject matter are landscapes and figures, plants and insects, as well as scenes from daily life and plays on auspicious subjects. One of the masterpieces of this genre is a very rare rhinoceros horn cup, skillfully carved with a scene of the beloved poet, Tao Yuanming (365-427) seated beside a wine jar in a setting of bamboo and rocks admiring a sprig of chrysanthemum, his favorite flower, 17th century (estimate: $200,000-300,000). Also offered is a very rare inscribed rhinoceros horn cup, a classic carving of a classic carving of a male figure in a landscape bearing a poetic inscription, 17th century (estimate: $120,000-180,000); and an extremely rare rhinoceros horn cup, supported by a squatting monkey symbolizing longevity, 17th/18th century (estimate: $60,000-80,000).

A very rare rhinoceros horn cup 17th century. Finely carved with the poet Tao Yuanming admiring a chrysanthemum sprig while seated beside a wine jar in a setting of bamboo and rocks, some forming the handle at one end below a pine branch that continues over the rim 6.3/8 in. (16.2 cm.) long. Estimate: $200,000-300,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

A very rare inscribed rhinoceros horn cup, 17th century. Very finely carved with a scene of a young man punting a flower-filled boat through cresting waves, with tree-form handle and rock-carved interior, one side carved in relief with a ten-character inscription, zai lai hua jia zi song shi bu zhi nian 5½ in. (14 cm.) long. Estimate: $120,000 - $180,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Ivory carvings

Ivory carvings that demonstrate an extremely high level of precision of carving and exquisite workmanship are very valuable. The beauty of the material, along with its smooth feel and the lovely sheen and color that comes with aging, makes carved ivory a favorite for collectors around the world.

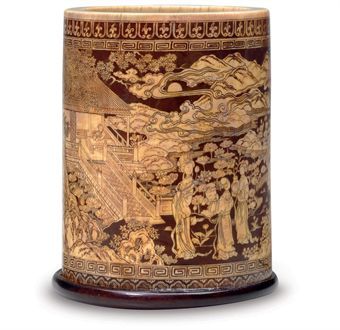

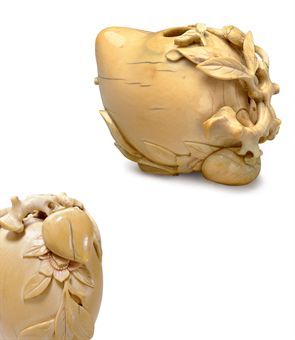

Complex in design is an exceptional carved ivory brush pot, 17th/18th century (estimate: $100,000-150,000). This brush pot is finely and deeply carved with an intricate gathering of Daoist immortals in a landscape setting. Another ivory brushpot offered is an unusual reverse-decorated lacquered brushpot, 18th/19th century, finely and delicately drawn with a continuous scene of ladies and their attendants by a lotus pond (estimate: $20,000-30,000). A similar example decorated with panels of flowers is in the Qing Court collection. Further highlights include a rare ivory peach-form water pot, Yongzheng/Qianlong Period (1723-1795) (estimate: $20,000-30,000) and a finely carved ivory wrist rest, Qianlong Period (1736-1795) (estimate: $20,000-30,000), both probably from the Imperial workshops; and an attractively carved ivory figure of a lady, 18th/19th century (estimate: $12,000-18,000).

An exceptional carved ivory brush pot, 17th/18th century. Finely and deeply carved with an intricately conceived gathering of Daoist immortals in a landscape setting below a narrow band of Buddhist and Daoist emblems, with a band of key fret on top of the rim - 6 in. (15.2 cm.) high. Estimate : $100,000 - $150,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

An unusual reverse-decorated lacquered ivory brush pot, 18th/19th century. Delicately reverse-decorated on a brown lacquer ground with a continuous scene of ladies and their attendants in a garden setting with a lotus pond and pavilion on one side, between decorative borders, wood base. 5½ in. (14 cm.) high. Estimate : $20,000 - $30,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

A rare ivory peach-form water pot. Yongzheng/Qianlong period (1723-1795). Carved in high relief at one end with a leafy gnarled branch and with a bat at the other end, with a peach and flower on the underside. 2¾ in. (7 cm.) long, cloth stand. Estimate : $20,000 - $30,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

A finely carved ivory wrist rest. Qianlong period (1736-1795). Finely carved on the concave side with a gathering of scholars in a mountain retreat and on the convex reverse with sampans sailing in a river. 9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm.) long, box. Estimate : $20,000 - $30,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

An ivory figure of a lady, 18th/19th century. Carved following the natural curve of the tusk, her hands hidden within the sleeves of her long robes, and her hair drawn up under a cloth head covering. 9¾ in. (24.8 cm.) high, wood stand. Estimate: $12,000-18,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Works of Art

With its excellent array of aesthetic and academic works of art, the sale offers the perfect opportunity to strengthen a collection or inspire interest in this fascinating field. Among the highlights are a very rare imperial Songhua stone inkstone, box and cover, Qianlong Nianzhi fourcharacter mark and of the period (1736-1795) (estimate: $250,000-280,000), esteemed not only for its color, but for its effectiveness and ease in the grinding of the ink; a very rare zitan and lingzhi fungus table screen, Qianlong period (1736-1795) (estimate: $150,000-180,000), both botanically rare and auspicious; a rare large inscribed Duan stone scholar’s rock, 18th/19th century (estimate: $60,000-80,000), unique in size, naturalistic shape and its carved decoration of bamboo, orchid, chrysanthemum and plum blossom; and two paintings- Happiness through Chan Practice: Portrait of Wang Shizhen, a handscroll by Yu Zhiding (1647-1716) depicting the writer and poet dressed as a Buddhist monk (estimate: $120,000-180,000) and a hanging scroll titled Peach Blossoms amidst Flowing Waters: Portrait of Qiao Lai by an anonymous 17th century artist (estimate: $30,000-50,000).

A very rare imperial Songhua stone inkstone, box and cover, Qianlong Nianzhi fourcharacter mark and of the period (1736-1795). The fine soft grey-green inkstone with a lingzhi-shaped well, and an outline conforming to that of the shallow box and cover which is finely carved on top through the grey-green outer layer to the darker grey under layer with a pair of cranes standing below the branch of one of the two pine trees at the sides, the four-character mark carved in a line on the base of the inkstone. Songhua stone box and cover: 3¾ in. (9.5 cm.) long; original fitted brocade box with paper label inscribed, Yuzhi Songhe tu xiao songyan, (Imperially made small ink stone with red color picturing pine and crane) on inside of cover. Estimate: $250,000-280,000). Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Provenance: Sotheby's, Hong Kong, 17 November 1988, lot 249.

Mary and George Bloch Collection; Sotheby's, Hong Kong, 23 October 2005, lot 149.

Notes: Beginning in the Kangxi period Songhua stone became one of the preferred stones, along with duan and she, for use in the carving of inkstones. Songhua stone was esteemed for not only its color, but especially for its effectiveness and ease in the grinding of the ink. The stone came from Jilin, a fact incorporated into a poem by the Qianlong Emperor, in which he mentions that "Songhua yu" (Songhua 'jade') came from the convergence of the Songhua and Heilong rivers in Jilin, and that it could be used for inkstones. In the article 'Songhua shi yan' (Songhua inkstone), Wenwu, 1980:1, pp. 86-7, Zhou Nanquan notes that in the 39th year of Qianlong's reign (1774) official records mention a total of 120 pieces of Songhua stone. Further records from the same year note that on three occasions thirty-eight pieces of raw material from Jilin province were sent to the palace. Of these, five pieces were used to carve eight inkstones and their boxes, as it was customary during the Qianlong period for the boxes of Songhua inkstones to be carved from the same stone, often utilizing the different strata of color found in the stone to great effect. During this period the Emperor even commissioned court painters to create the designs for the covers, creating an artistic link between certain types of paintings and the motifs found on the covers of some inkstone boxes.

A Songhua inkstone with similar well and cover with very similar design were included in the Min Chiu Society Thirtieth Anniversary Exhibition, Selected Treasures of Chinese Art, Hong Kong, 1990-91, no. 238. Another of related shape and design, of Yongzheng date, is illustrated in Special Exhibition of Sunghua Inkstone, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1993, no. 47. See, also, the inkstone of rectangular shape with pine and cranes on the cover, dated to the Qianlong period, illustrated ibid., no. 57.

A very rare zitan and lingzhi fungus table screen, Qianlong period (1736-1795). The zitan table screen with upward-sliding removable back made specifically to display the dried natural fungus head which is framed by a border of conforming outline. 12½ in. (31.7 cm.) high, 11 7/8 in. (30.1 cm.) wide. Estimate: $150,000-180,000). Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Provenance: Sydney L. Moss Ltd., London, 1986.

Literature: Paul Moss, The Literati Mode, London, 1986, no. 66.

Exhibited: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1997 - 2007.

Notes: This exceptional zitan table screen has a fine specimen of lingzhi fungus set into it. This is both botanically rare and highly auspicious. Chinese art abounds with symbols of longevity, but none is so revered as the lingzhi fungus. As can be seen in the current example, this type of fungus has a rich, deep color and a glossy sheen, which makes it look as if it has been lacquered. This fungus, which grows on the roots of trees, and itself has a woody texture, is known by the Latin name Ganoderma lucidum. The name Ganoderma comes from the Greek ganos, meaning brightness or sheen, and derma, meaning skin - hence, shining skin. Lucidum comes from the Latin word for shining, which re-emphasizes the glossiness of the fungus's surface. Although it is found in southern China, it is rare in northern China and the hunt for lingzhi fungus is a frequent topic in Chinese literature and iconography. Legend associated the so-called 'fungus of immortality' with the mythological islands in the Eastern Sea, which were supposed to be the home of the immortals. When they were found, these lingzhi fungi were greatly valued, and most impressive specimens were so revered that they had to be presented to the emperor.

Amongst the properties for which the lingzhi is admired are its hardness and the fact that it retains its shape even after many years. The fungus set into the current screen is a testament to that. The Chinese have also traditionally ascribed great medicinal properties to the fungus, and it was even believed to have the ability to revive the dead. It is thus regarded as a plant that can ward off evil and ensure the vigor of its possessor. Since the head of ruyi sceptres are frequently shaped like a lingzhi fungus, and ruyi symbolize 'everything as you wish', lingzhi have also become associated with wish-granting.

The most popular view of the lingzhi fungus is as a symbol of, or wish for, longevity. As such it is frequently depicted with other symbols of longevity, such as the spotted deer. It is often depicted in an imperial context particularly at the time of an emperor's birthday. An example of this is the famous painting by Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining) commissioned in 1724 for the birthday of the Yongzheng emperor. This painting, entitled Pine, Hawk and glossy Ganoderma, is preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing, and illustrated in China: The Three Emperors 1662-1795, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2006, p. 183, no. 79. In this painting the white hawk is intended to proclaim that a virtuous emperor is on the throne and that he has the Mandate of Heaven to rule the empire. The venerable pine tree provides one auspicious symbol of longevity, but it is the three groups of richly-colored lingzhi that draw the viewer's eye and subsequently lead it to the white hawk.

The Qianlong Emperor, from whose reign the current screen probably dates, was particularly fond of lingzhi, and four Qianlong zitan screens with inset lingzhi are preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. The dated inscriptions on two of them have been recorded. The text of such inscriptions was written by the Qianlong emperor and applied to the screens in accordance with his orders. One of the screens dated by inscription to AD 1767 is illustrated by Wang Jie et al., Shequ baoji xubian [Precious Collection of the Stone Pavilion, Supplement], 1793, 7 vol., reprint by the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1971, pp. 4054 ff. In the inscription the Qianlong emperor notes that he admires the lingzhi on the screen for its ageless beauty and its lofty character. The other screen from the Qing court collection dated by its inscription to AD 1774 is illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum - 54 - Furniture of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (II), Hong Kong, 2002, pp. 192-3, no. 169. (Fig. 1) In the imperial inscription on this screen the emperor muses that the fungus may be several thousand years old, and that during the reign of (the mythical) Emperor Shun it may have enjoyed the shade of auspicious clouds, while during the reign of Emperor Yao it may have been nourished by precious dew. For a translation of the whole inscription see China: The Three Emperors 1662-1795, op. cit., p. 441.

Such screens were greatly prized for their rarity, beauty and auspicious associations. They would have been appreciated for their visual impact, but the presence of the real lingzhi fungus was also believed to promote health and long life. Despite these extra qualities, the Qianlong emperor makes it clear in his 1767 inscription that he does not necessarily value the screen as an aid to health, but simply as an object of beauty. Interestingly the decoration on the lower part of the frame of the current screen is of the same form as that on the frame of the Qianlong lingzhi screen in the Palace Museum dated to AD 1774. It seems probable that the two screens were made at around the same time.

A rare large inscribed Duan stone scholar’s rock, 18th/19th century. The vertical 'rock' well carved in low relief on one side with a vignette of bamboo, plum blossom, orchid and chrysanthemum, and inscribed with a poetic inscription signed Liqi Yu, with two seals shanxing (prunus) and shizhai, the purplish-brown stone with numerous pale grey-green eyes. 21 in. (53.5 cm.) high, wood stand. Estimate: $60,000-80,000). Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Provenance: E & J Frankel, Ltd., New York, late 1970s - early 1980s.

Notes: The poetic inscription refers to the four elements of the decoration - bamboo (symbol of the scholar), orchid (symbol of filial piety), chrysanthemum (symbol of fidelity), plum blossom (symbol of renewal) - and may be translated:

'Praise to the good official who bends but does not shatter.

Wild orchid fragrance, mysterious as love between brothers.

Held by deep autumn frost the chrysanthemum blooms through snow.

As the plum blossom opens winter closes and spring begins.'

This rare scholar's rock is a very unusual use of duan stone, which is usually used to make inkstones. The combination of the stone, the size, the attempt at a naturalistic shape, and the carved decoration all make this piece unique among scholar's rocks.

Yu Zhiding (1647-1716), Happiness through Chan Practice: Portrait of Wang Shizhen. Handscroll, ink and color on silk. 13 7/8 x 31½ in. (35.3 x 80 cm.) Signed: "Respectfully painted, Yu Zhiding of Guangling". Estimate: $120,000-180,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Five seals of the artist

Frontispiece by Lin Ji (1660-after 1720), signed and with 3 seals

Five collectors' seals of Xiang Hanping (1890-1978), a general in the Nationalist Army

Colophons by Mei Geng (1640-1722, dated gengchen year (1700), with 3 seals); Lin Ji (with 3 seals); Zha Sheng (1650-1707, with 4 seals); Wang Yi (1671-1706, dated gengchen year (1700), with 3 seals); Zha Siting (?-ca. 1726), with 3 seals); Yu Zhaosheng (late 17th-early 18th century, with 3 seals); Feng Tingkui (1649-1700, with 2 seals); Chen Yixi (1648-1709, with 3 seals); Liu Shiling (Qing dynasty, with 3 seals); Zhu Zaizhen (with 3 seals); Jiang Renxi (late 17th-early 18th century, dated 39th year of the Kangxi era (1701), with 3 seals); Huang Yuanzhi (with 4 seals); Wang Danlin (with 1 seal); Sun Zhimi (1642-1708), with 3 seals); and Qian Mingshi (late 17th-early 18th century, with 3 seals)

Titleslip by Xiang Hanping, dated jiaxu year (1934) and with 1 seal.

Notes: Yu Zhiding was a versatile painter who was most highly respected for his skillful and lifelike portraits. He served for several years as an official painter in the court of Emperor Kangxi. After retiring from official service in 1690, he returned to his home and painted the likenesses of many of the most illustrious men of the period. This portrait depicts Wang Shizhen (1634-1711), who was a member of a well established family, an accomplished scholar, and an effective government official. A child prodigy, Wang is best known for his talents as a prolific poet and writer.

Yu Zhiding painted at least four other portraits of Wang Shizhen, which was a result of the men's friendship. These portraits feature highly realistic depictions of Wang Shizhen that make use of modeling techniques derived from Western painting traditions. The surrounding landscapes were often painted by other artists--a collaborative practice for which Yu Zhiding was well known. In the title of the painting and in the depiction of Wang wearing monk's robes and shorn hair, Yu Zhiding illustrates Wang's connection with Chan Buddhism. Innovative for painting his subjects in psychologically revealing settings, Yu also included a reference to Wang's reputation as an enthusiastic bibliophile who amassed a huge library by showing him with stacks of books.

Wang Shizhen's portrait is followed by fifteen colophons written by friends and colleagues of Wang Shizhen and suggest that the painting was made in or just before 1700. Most of the authors had careers in government service and many were talented calligraphers. The majority of these comments not only praise Wang Shizhen's accomplishments and upright character but also describe his embodiment of Chan values and philosophy.

Anonymous, 17th century, Peach Blossoms amidst Flowing Waters: Portrait of Qiao Lai. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. 50 3/8 x 24½ in. (128 x 62.2 cm.). Estimate: $30,000-50,000). Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

5 colophons inscribed on the mounting by (clockwise from top left) Zhang Ying (1637-1708, dated gengshen year (1680), with 3 seals); Wang Shizhen (1634-1711, with 3 seals); Wang Wan (1624-1691, with 3 seals); Shi Runzhang (1618-1683, dated xuwu year (1678), with 3 seals); Zhu Yizun (1629-1709, with 3 seals); Wang Maolin (1640-1688, dated gengshen year (1680), with 3 seals); Mao Qiling (1622-1716, with 1 seal); Chen Weisong (1625-1682); Mao Qiling (with 2 seals); Li Liangnian (1635-1694, with 3 seals); and Sun Zhiwei (1631-1697, with 3 seals)

Two collector's seals of Wu Puxin (1897-1987), whose important collection was known as the Sixuezhai Collection

Provenance: Sotheby's, New York, 8 December 1987, lot 13.

Notes: As indentified by the colophons, the figure seated reading in a boat is Qiao Lai (1642-1694), who was a native of Baoying in Yangzhou. After he attained the prestigious jinshi ("presented scholar") degree in 1667, Qiao Lai held several important posts in Emperor Kangxi's court. However, he was implicated in a scandal and in 1688 retired to a life of literary pursuits and garden restoration. He was also an accomplished painter of landscapes. Three portraits painted by Yu Zhiding (1647-1716) of Qiao Lai in the Nanjing Museum clearly depict the same man (reproduced in Ming Qing renwu xiaoxianghua xuan, cat. nos. 31-3 and discussed by Richard Vinograd in Boundaries of the Self: Chinese Portraits 1600-1900, pp. 53-4) and are rendered in a fashion similar enough to raise the possibility that Yu Zhiding painted this version as well.

The colophons that surround the portrait, which was probably painted in the 1670s, are all written by friends of Qiao Lai, who shared similar careers and literary prowess. Like Qiao Lai, five of the group achieved the jinshi degree and four others sat for a special official exam held in 1678-79. All served in the government and were accomplished authors of prose and poetry. Each illustrious friend inscribed a poem that described the paradisial spring garden which Qiao Lai is shown serenely enjoying, accompanied by the books that he collected and studied. Most eloquent is the poem by Wang Shizhen, who describes a fragrant world filled with swirling peach blossoms and celebrates Qiao Lai's sublime appreciation of the moment and indifference to fame and fortune.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F31%2F55%2F577050%2F66184124_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F63%2F119589%2F66179442_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F05%2F577050%2F65768905_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F92%2F30%2F119589%2F65585173_p.jpg)