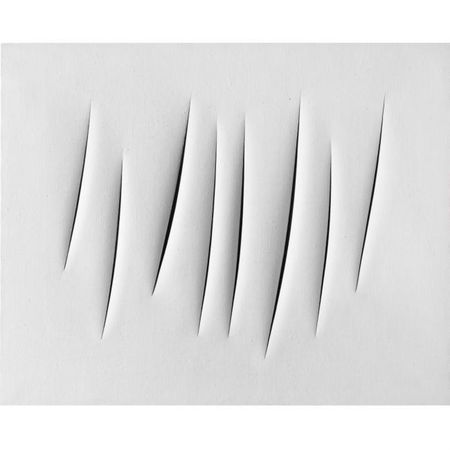

Lucio Fontana (1899 - 1968), Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1965.

Lucio Fontana (1899 - 1968), Concetto Spaziale, Attese. photo courtesy Sotheby's

waterpaint on canvas, signed, titled and inscribed Con questa pioggia é impossibile lavorare - W il sole on the reverse. Executed in 1965; 80 by 100cm - Estimate 1,500,000—2,000,000 GBP. Lot Sold 2,281,250 GBP

PROVENANCE: Acquired directly from the artist by the present owner in 1966

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana Catalogue Raisonné, Brussels 1974, Vol. II, p. 164, no. 65 T 99, incorrectly illustrated

Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana Catalogo Generale, Milan 1986, Vol. II, p. 578, no. 65 T 99, illustrated

Enrico Crispolti, Lucio Fontana Catalogo Ragionato, Milan 2006, Vol. II, p. 764, no. 65 T 99, illustrated

NOTE: "The discovery of the Cosmos is that of a new dimension, it is the Infinite: thus I pierce this canvas, which is the basis of all arts and I have created an infinite dimension, an x which for me is the basis for all Contemporary Art"

The artist cited in Exhibition Catalogue, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Lucio Fontana, Venice/ New York, 2006, p. 19

Lucio Fontana's stunning Concetto Spaziale, Attese from 1965 is an impressive example from the artist's celebrated Tagli series. Its scale and presence and the sharp contrast of the silken white surface with the blackness of the eight diagonally curving black slashes epitomises Erika Billeter's statement that: "Lucio Fontana... challenges the history of painting. With one bold stroke he pierces the canvas and tears it to shreds. Through this action he declares before the entire world that the canvas is no longer a pictorial vehicle and asserts that easel painting, a constant in art heretofore, is called into question. Implied in this gesture is both the termination of a five-hundred year evolution in Western painting and a new beginning, for destruction carries innovation in its wake" (Exhibition Catalogue, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Lucio Fontana 1899-1968: A Retrospective, 1977, p. 13). Having resided in the same collection since 1966, it is the first time that this masterpiece appears in public.

Compositionally dynamic and mesmerising in its beauty, Concetto Spaziale, Attese embodies the artist's revolutionary Spatialist theory while engendering a unique dialogue between colour and form. The white monochrome field of the canvas is an expanse of serenity, harnessing enduring and powerful connotations of innocence and purity. It also frames the white of light and heat; a beam of white light holds within it the full spectrum of colour, revealed when it is refracted through an optical prism; and white has often symbolised technology and the future, particularly in the decades following the Second World War. The alluring white arena of Concetto Spaziale, Attese is ablaze with energy, acting as apt parallel to Fontana's idea of the artist as the source of creative energy, and provides the perfect setting for his conception of pure space.

The eight elegantly vigorous and lyrically slender slashes simultaneously evince spontaneity and control, choreographed under the deft aegis of Fontana's blade into a rhythmic dance across the canvas. Here the artist discards conventional reverence for the canvas and his strokes of genius attest essential risk: if the cut deviated from Fontana's desired line, the entire canvas would have been discarded. Not only did the canvas need to be perfectly taut for a successful result, but the outcome depended on the moment of the chance of the performance. The pattern of slashes is a bravura exhibition of the unrepeatable moment, repeated; the immediacy of the artist's gesture is suspended in time. The speed of the action recorded has the effect of 'killing time', while the clarity of the eight linear strokes underlines the moment of their creation. However, although this painting radiates with a sense of the momentary, there is nothing haphazard about its making. A measured pair of diagonally curving strokes is the focal point of a perfectly harmonic composition, where the three cuts on each side of the central pair are analogously disposed. Of equal importance are the carefully deliberated spaces between: the first inter-cut break from left is neatly echoed by the seventh, while the third finds almost exact counterpart in the fifth. The resulting rhythmic cadence is quite transfixing and unique among the tagli series: with nervous energy and dynamic force, space pulses through the openings.

Created one year before Fontana was awarded the International Grand Prize for Painting at the XXXIII Venice Biennale, this major work encapsulates the artist's wide-ranging ambitions as a pioneer of what art could achieve. Having broadcast his theory of Spatialism in five manifestos between 1946 and 1952, Fontana was to forge unthinkable advancements in artistic ideology, seeking to create a new age of Spatialist art that engaged technology and found expression for a fourth dimension and Infinity. Having been almost exclusively a sculptor until his forties, his oeuvre consistently referenced an artwork's material properties. Fontana's inquiry into the indeterminate zone between painting and sculpture was rooted in his abstract and figurative sculpture of the 1930s, which tested the gap between solid and void both by carving marks out of material and by creating freestanding marks in space. In close relation to Concetto Spaziale, Attese, the tavolette graffite (scratched tablets) from 1931 display fluid incisions in cement that merge and dissolve as if free-floating. Even at this early stage Fontana evinced a disregard for traditional techniques and an interest in infinite space that would be significantly developed through painting. In the Natura cycle of imperfectly shaped terracotta spheres (1959-60) deep gashes suggest orifices and geographical fault lines, further freeing the artist from the constraints of two-dimensionality. In Concetto Spaziale, Attese Fontana dissects the very concept of painting, undermining forever the flat picture plane. As Fontana declared in his last recorded interview, given in 1968: 'I make a hole in a canvas in order to leave behind the old pictorial formulae, the painting and the traditional view of art and I escape, symbolically, but also materially, from the prison of the flat surface' (in conversation with Tommaso Trini, 19 July 1968 in: Exhibition Catalogue, Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum; London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Lucio Fontana, 1988, p.34).

Fontana offers an original interpretation of the artist's gesture: instead of letting it remain on the surface he makes it penetrate through the canvas. This edited canvas is itself an act of art historical editing: the slashes propose questions concerning the relationship between the surface and the void, about the hidden properties of material, and regarding our place in the world around. Richly connotative, we are confronted with a multitude of sensual suggestions - at slits between theatre curtains, glimmers between lips, surgical incisions - but above all, through the superbly simple flick of a knife, Fontana initiated fissures in artistic convention that were to pierce the very meaning of art.

Sotheby's. 20th Century Italian Art, 15 Oct 10, London www.sothebys.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F31%2F119589%2F66173465_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F37%2F119589%2F66154920_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F35%2F87%2F119589%2F66137125_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F82%2F19%2F119589%2F65179163_p.jpg)