Religious life in "The world of Kubilai Khan" @ Metropolitan Museum New York

Buddha, either Shakyamuni or Akshobhya, late 13th–early 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Gilt bronze; H. 13 in. (33 cm), W. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm). Lent by The Palace Museum

Although this Buddha's pointed topknot, triangular face, narrow nose, powerful physique, and scanty clothing are based on Indian artistic traditions, several features suggest that this sculpture was made in China. These include the pudginess of the hands and feet and the patterning in the drapery beneath the crossed legs and on the left shoulder. The lowered right hand reaching toward the earth identifies this sculpture as a representation of either the historical Buddha Shakyamuni or the celestial Buddha Akshobhya, who are the only two Buddhas known to make such a gesture.

Buddhism

When the Mongols first entered China in the early thirteenth century, Chan (Zen) was the most prominent of the several forms of Buddhism practiced in China, but under Khubilai Khan, the imperial house converted to Esoteric Buddhism, which had been brought to China by Tibetan lamas. The consequent influence of the Nepali-Tibetan (or, more broadly, Indo-Himalayan) tradition on Buddhist art at the imperial court was transformative; on view in the exhibition are several bronze sculptures that are representative of this new, hybrid style. Also on view are objects that were used during elaborate Esoteric rituals, among them painted mandalas and sculptures of terrifying protective deities.

Outside the imperial court, Chan Buddhism still held sway, especially among the educated classes. Chan emphasized meditation and mindfulness in all activities as the means to achieve enlightenment. The exhibition includes paintings by and portraits of several Chan monks, including the famous Chan master Zhongfen Mingben (1263–1323). Other works on view were produced in North and South China before the Mongol conquest and reunification. These include paintings and sculptures associated with the Pure Land tradition, whose adherents were devotees of the celestial Buddha Amitabha. Also noteworthy is the imagery shared between multiple Buddhist practices, including manifestations of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin) and representations of the guardians known as arhats, or luohans.

Bodhisattva Manjushri, dated 1305, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Gilt bronze; H. 7 1/16 in. (18 cm), W. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). Lent by The Palace Museum

This sculpture is a rare example illustrating the introduction of Nepali artistic traditions into Chinese art during the Yuan dynasty. The bodhisattva's square face and minimal clothing derive from Indian and Himalayan conventions, the appearance of which in Chinese Buddhist art is usually traced to Anige (1245–1306), a young Nepali artist who first worked for a monastery in Central Tibet and was later introduced to Khubilai Khan by the monk Chogyal Phagspa, the first state preceptor of the Mongol Empire. Anige played an important role at court, where he was eventually appointed Controller of Imperial Factories.

Monk's-Cap Ewer, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Porcelain; H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm), Diam. of rim: 6 7/16 in. (16.3 cm). Lent by Capital Museum

Ewers of this type, which are thought to emulate the shape of a Tibetan monk's hat, are usually dated to the early fifteenth century, but this example, which was unearthed from a Yuan-period site in Beijing in 1965, provides evidence that such vessels were produced even earlier, in the fourteenth century. It seems likely that the development of monk's-cap ewers can be traced to the strong ties between the Mongol court and Tibet during the Yuan dynasty.

Tibetan-Style Ewer, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Porcelain (Qingbai ware); H. 9 13/16 in. (24.9 cm), Diam. of rim: 3 9/16 in. (9 cm), Diam. of foot: 4 7/8 in. (12.4 cm). Lent by Capital Museum

This intriguing object was found in the tomb of a Kashmiri monk whose son was an important Yuan official in the early fourteenth century. It may be one of the earliest examples of a type of vessel known later in both Tibet and Mongolia. The shape, in particular the struts along the sides and the high edge at the neck, suggests that it was copied from a prototype in another material, possibly leather or wood. Although it was found in northern China, it was made in the south and provides a rare example of the earliest non-Chinese shapes to be produced by the famous kilns at Jingdezhen.

Two Arhats (Luohans) in a Landscape, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Tibet, Hanging scroll; color and gold on cotton; Image: 28 3/8 x 13 3/8 in. (72 x 34 cm). Lent by The Cleveland Museum of Art. Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund, 1988.103

The popularity of arhats in Chinese art had a lasting impact in Tibet. While the treatment of space in this painting and details such as the trees, plants, and clothing derive from Chinese traditions, it seems likely that the work was produced in Tibet. The composition, with one figure above the other, has parallels in Tibetan painting, as does the use of cloth rather than silk for the support. Tibetan phrases on the front of the painting give directions for the use of color, while a standard Buddhist incantation, or mantra, written in the Newari script is found at the back.

Unidentified Artist, Arhat (Luohan) in a Landscape, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 48 1/4 x 20 3/4 in. (122.6 x 52.7 cm); Overall with knobs: 87 x 26 1/2 in. (221 x 67.3 cm). Lent by Kimbell Art Museum

Arhats, the guardians of the Buddhist faith, do not appear in Indian or Southeast Asian art. Devotion to a specific group of sixteen arhats, better known by the Chinese term luohans, and the representation of these figures in the visual arts, which began in China during the Tang dynasty, was based on a text brought to China in the seventh century. This text endows the arhats with magical powers and describes the paradisiacal realms they inhabit.

This painting illustrates the Chinese perception of arhats, who are generally depicted wearing clerical garments and are alternatively shown with either Chinese or "foreign" (presumably Indian or Central Asian) physiognomies. The broad face and powerful features of this figure reflect the style of Lu Xinzhong (active thirteenth century), an artist based in the Ningbo region known for his paintings of arhats. However, the background landscape, the rendering of the trees, and the treatment of the caps of the foreground waves as long, gnarled shapes help date this painting to the early fourteenth century.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, dated 1282, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China (probably Hebei province). Willow with traces of pigment; single woodblock construction; a. Guanyin: 39 1/4 in. (99.7 cm); b. Inscribed block: H. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm), W. 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm), D. 1 in. (2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1934 (34.15.1a, b

)Inscribed at the back with the date 1282, this sculpture of the benevolent Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara is one of very few Chinese examples from any historical period that can be precisely dated. It also provides one of the earliest examples of the sophisticated blending of Chinese and Indo-Himalayan imagery that characterizes Buddhist art of the Yuan dynasty.

While the long undergarment and covering apron, the narrow scarf covering the shoulders, and the floral patterns on the necklace are typically Chinese, the slightly twisting torso, muscular chest, and high cheekbones have Indo-Himalayan parallels, as does the rendering of the hair, which rises above the head in long strands that end in spirals. It is interesting that, in India and the Himalayas, this hairstyle is not found, as here, on benign deities but on fearsome protectors.

Unidentified Artist, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water-Moon Manifestation, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 43 3/4 x 30 in. (111.2 x 76.2 cm); Overall with mounting: 89 x 30 in. (226.1 x 76.2 cm); Overall with knobs: 89 x 32 1/4 in. (226.1 x 81.9 cm). Lent by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 49-60

Representations of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara seated on a promontory overlooking rapidly churning waters—known as the Water-Moon manifestation—appear frequently in the fourteenth century. A pine tree and a waterfall fill the background, and a glass vessel (possibly from an Islamic center) holding a willow branch is placed on a cloth to the right of the seated deity. Thought to have healing powers, the willow is often associated with Avalokiteshvara. The shawl worn by the bodhisattva and its wide hems that fall in broad, circular pleats are typical of the Yuan period.

Unidentified Artist, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara as Fish-Basket Guanyin, early 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll mounted as a panel; ink and color on silk; Image: 33 1/4 x 14 5/16 in. (84.5 x 36.4 cm); Framed: H. 65 3/8 in. (166 cm), W. 22 1/4 in. (56.5 cm), D. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm). Lent by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Special Chinese and Japanese Fund, 05.199

An interesting story underlies the development of a manifestation of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara as the beautiful woman Malangfu, whose identifying attribute is a fish basket. According to legend, she appeared one day in a village that was not yet Buddhist and offered to marry any man who could recite the full text of a sutra of her choice. A man named Ma won, and Malangfu became his wife.

In this painting, the bodhisattva wears secular clothing rather than the Indian-style garments usually worn by Buddhist deities. The embroidered floral sprays on her clothing and the lush bands at the collar and hems reflect the Mongol interest in gold textiles. The delicate chain found beneath the apron differs from the heavier jewelry often worn by Buddhist deities in Chinese art. It may have been inspired by Mongol jewelry with filigree and embedded stones.

Unidentified Artist, Portrait of the Monk Zhongfeng Mingben, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and light color on silk; Image: 48 5/8 x 20 3/16 in. (123.5 x 51.3 cm). Lent by Shôkoku-ji, Jishô-in

Easily identified by his rounded face and slightly sagging eyes, Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323) was one of the most important monks and teachers in China during the fourteenth century. In this portrait, he sits in meditation on an elegant piece of cloth (possibly a carpet) with his shoes placed on a smaller rock in front of him. He wears traditional monastic robes with flowing hems typical of the fourteenth century. The towering pine and delicate bamboo in the background follow the ink-painting conventions associated with the Chinese literati. The landscape is typical of the Yuan dynasty, when such monochromatic backgrounds were first used for the portraits of Buddhist monks.

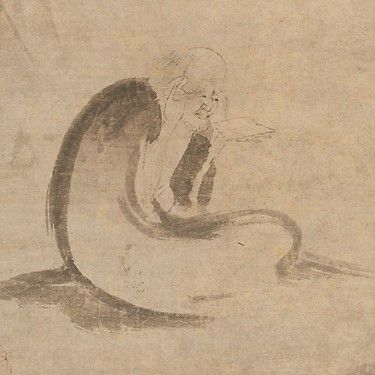

Unidentified Artist, Buddha Shakyamuni Descending from the Mountains, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink on paper; Image: 33 7/16 x 12 13/16 in. (85 x 32.6 cm); Overall with mounting: 64 11/16 x 13 9/16 in. (164.3 x 34.5 cm). Lent by Hatakeyama Memorial Museum of Fine Art

Monochromatic ink paintings of Buddhist subjects are often linked to the Chan (or Zen) tradition. The iconography of this painting, which shows the Buddha descending from a mountain after several years of meditation in a wilderness, is also frequently associated with Chan. While the painting does not have a canonical source, historical records suggest that such images of the Buddha were first developed in China in the eleventh or twelfth century.

Here, the Buddha stands with his robes fluttering before him, suggesting that the wind is pushing him down the mountainside. He is unshaven as befits his time as a hermit. The poem at the top was written by the famous monk Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323) (see previous image) and alludes to the difficulty of reentering the phenomenal world after one has achieved a state of enlightenment.

Cup Stand with Eight Buddhist Treasures, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Silver with repoussé decoration; H. 1/2 in. (1.3 cm), Diam. of rim: 6 1/8 in. (15.6 cm), Diam. of foot: 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2006 Benefit Fund, 2007 (2007.187)

Among the objects contained within the lotus petals that decorate the interior of this cup stand are seven of the Eight Buddhist Treasures: a wheel, an endless knot, a conch shell, a victory banner, a lotus, a pair of fish, and a treasure vase. The traditional eighth treasure, a parasol, has been substituted here by a pair of elephant tusks.

Many of these motifs, both individually and as part of the group of eight, can be seen on the Yuan-dynasty metalwork and porcelain on view in this exhibition (see next image). These objects appear to be the first examples to depict the Eight Treasures, which would later become an important theme in Chinese and Tibetan art.

Bowl with Eight Buddhist Treasures and the Tibetan Syllable "Hum", Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Porcelain with raised decoration in overglaze enamels and gold; H. 3 1/8 in. (8 cm), Diam. of rim: 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm), Diam. of foot: 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm). Lent by Shanghai Museum

This type of porcelain, with raised gilded lines and overglaze enamels, was completely unknown until its recent discovery at Yuan archaeological sites in North China, particularly Inner Mongolia. The raised lines, use of gold, and Buddhist symbols all point to a Mongol connection, from the period following the introduction of Indo-Himalayan Buddhism to Mongolia. This bowl is the first of its kind to be exhibited outside China.

Wang Zhenweng (Chinese, active 14th century), Portrait of the Japanese Monk Kokan Shiren, dated 1343, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 48 1/16 x 22 7/16 in. (122.1 x 57 cm). Lent by Tôfuku-ji, Kaizô-in

The inscription at the top of this portrait indicates that it is one of three such portraits produced in China by the little-known artist Wang Zhenweng. It also identifies the subject as the important Japanese monk Kokan Shinren, who trained in the Linji (Rinzai) tradition of Chan (Zen) Buddhism. Known for promoting the use of physical punishment as a goad to advancement, monks in this lineage are often portrayed holding the large sticks they used to prod students.

Kokan Shinren spent his lifetime working and studying in the Kyoto area, where he was appointed abbot of the famed Tôfuku-ji temple in 1332 and later served in the same capacity at the Nazen-ji temple. In this portrait, he sits on a carved red-lacquer chair that could only have been made in China, most likely in the south, where the lacquer industry flourished.

Unidentified Artist, Monk Reading a Sutra by Moonlight, ca. 1332, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink on paper; Image: 29 3/8 x 13 in. (74.6 x 33 cm); Overall with mounting: 59 x 13 5/8 in. (149.9 x 34.6 cm); Overall with knobs: 59 x 15 1/2 in. (149.9 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1982 (1982.3.2)

Paintings of monks reading sutras by moonlight reflect the Chan, or Zen, emphasis on remaining forever mindful, even during daily activities, in order to achieve enlightenment. Here, an elderly cleric with scraggly hair and a sparse beard sits in a remote landscape, reading a sutra. He holds the text in his left hand and twirls one of his long eyebrows with his right. The delicate rendering of the face is complemented by the thick, dark brushstrokes in his clothing. The poem, composed and written by the monk Yuxi Simin (active fourteenth century), reads:

Just this one fascicle of sutra,

The words are often difficult to make out.

When the sun comes up, the moon also sets,

When will I finish reading it?

Buddha Shakyamuni with Manjushri and Samantabhadra, late 12th–early 13th century, Jin dynasty (1115–1234)–Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 43 1/8 x 21 in. (109.5 x 53.3 cm). Lent by Jôbodai-in

Stylistic features such as the unarticulated outlines of the figures, the relatively flat picture plane, and the use of gold highlights suggest that this may be a rare example of a hanging scroll from northern China. An inscription on the foreground pillar states that the painting is based on the Lotus Sutra, one of the most influential texts in East Asian Buddhism. The triad at the top—the historical Buddha Shakyamuni flanked by the bodhisattvas Manjushri (seated on a lion), who embodies wisdom, and Samantabhadra (seated on an elephant), who symbolizes virtue—was often associated with this text in China and Japan. (See another image of Manjushri and Samantabhadra.) They are accompanied by a group of ten figures, who most likely represent the historical disciples of the Buddha, and two Indian deities: Brahma (with folded hands) and Indra (holding an incense burner).

Sutra Box with Design of Pheasants and Flowers, dated 1315, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Black lacquer with gilded engraved lines (qiangjin); H. 10 1/8 in. (25.7 cm); W. 9 3/16 in. (23.3 cm); L. 15 3/4 in. (40 cm). Lent by Kyushu National Museum

This is one of several boxes used to store Buddhist texts that are now preserved in Japanese collections. It is decorated using the qiangjin technique, which involves incising into a lacquer surface and then filling the incisions with gold leaf or pigment.

These boxes are the earliest known examples of the use of this technique. The top and side are filled with ogival cartouches that may ultimately derive from Islamic art. Each contains a pair of peacocks flying against a background of clouds. The division of the surface with lines or cartouches, the size of the blossoms, and the twisting of figures, birds, rocks, leaves, and flowers to create the illusion of depth exemplify the art of the Yuan dynasty.

Bodhisattva Manjushri, 12th–13th century, Xixia dynasty (1032–1227). Hanging scroll mounted as a panel; ink and color on silk; Image: 37 13/16 x 23 5/8 in. (96 x 60 cm); Framed: 52 3/8 x 28 3/8 in. (133 x 72 cm). Lent by The State Hermitage Museum

Manjushri, the embodiment of wisdom, appears in the visual arts as both an independent deity and as an attendant to a Buddha. In this painting, Manjushri, riding a lion, is led by a Central Asian groom wearing a red hat, a tunic, and black boots. The youth to his left represents the pilgrim Sudhana, the protagonist of the Flower Garland Sutra, one of the most influential texts in China from the tenth to the fourteenth century. The third figure, who holds a staff, may represent a Kashmiri monk who was famous for having twice seen Manjushri during visits to China in the seventh century. However, his Chinese-style clothing and hat suggest that this figure may be a Chinese scholar-gentleman rather than the Indian cleric.

Bodhisattva Samantabhadhra, 12th–13th century, Xixia dynasty (1032–1227). Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 40 13/16 x 22 5/8 in. (103.7 x 57.5 cm); Framed: 53 7/16 x 29 in. (135.8 x 73.7 cm). Lent by The State Hermitage Museum

Paintings discovered in the early twentieth century during excavations at Kharakhoto (known in Chinese as Heicheng, or the "black city") remain among the most important works for the study of both Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist art from the twelfth to the fourteenth century.

This example provides important information regarding Buddhist art in northern China prior to the Mongol conquest (far fewer paintings from the north have been preserved than from the south). The heavy robes and lush jewelry worn by this bodhisattva, as well as the canopy and flying celestial (apsara) at the top of the painting, parallel the style of northern Chinese murals.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water-Moon Manifestation (Shuiyue Guanyin), mid- to late 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Gilt bronze; H. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm), W. 7 5/8 in. (19.4 cm), D. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm); Overall (with block): H. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm), W. 9 in. (22.9 cm), D. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). Lent by Royal Ontario Museum, Dr. Herman Herzog Levy Bequest Fund

This bodhisattva can be identified as Avalokiteshvara by the Buddha seated above the diadem encircling his head and by the raised position of his bent right knee. (See another image of Avalokiteshvara.) Here he is seated in his Pure Land, or personal paradise, which originally was thought to be located in the Indian Ocean. In China, however, after the twelfth century, the location of the Pure Land shifted to Mount Putuo, an island off the coast of Zhejiang Province.

Representations of Avalokiteshvara seated in this fashion are also understood as references to his Water-Moon manifestation (see related image), which developed in China around the tenth century and quickly became one of the more prominent forms of this bodhisattva in East Asia. The square face and high, complicated headdress with braids recall Indo-Himalayan artistic traditions; both motifs parallel imagery found in contemporaneous Nepali and Tibetan works.

Buddha, either Shakyamuni or Akshobhya, dated 1336, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Gilt bronze; H. 8 7/16 in. (21.5 cm). Lent by The Palace Museum

Here, a Buddha extends his proper right hand toward the earth in bhumisparsha mudra, the most widely represented gesture in Indian and Tibetan Buddhist art from the twelfth to the fourteenth century. It is not surprising that this mudra also appears in sculptures produced in China during the Mongol period.

The Buddha's ushnisha, or cranial protuberance (a symbol of celestial wisdom), and the thin, clinging clothing also parallel Indo-Himalayan traditions. The rounded face and plump hands and feet, as well as the use of beading to define the hems of his robe, are, however, typically Chinese.

Unidentified Artist, Buddha Amitabha Descending from His Pure Land, 13th century, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 53 1/2 x 23 in. (135.9 x 58.4 cm); Overall with mounting: 95 3/4 x 31 3/4 in. (243.2 x 80.6 cm); Overall with knobs: 95 3/4 x 33 1/2 in. (243.2 x 85.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1980 (1980.275)

A barely legible inscription at the lower left of this painting indicates that it was produced in the Ningbo area, near Hangzhou, the capital of the Southern Song dynasty and a major center of Buddhist painting. The Buddha can be identified as the celestial (as opposed to historical) Amitabha by his standing diagonal position and lowered right hand.

In East Asia by the sixth century, Amitabha had become the focus of a practice based on a group of three related texts whose adherents sought to achieve rebirth in Amitabha's Pure Land, or personal paradise. This perfected world was believed to be an environment particularly conducive to attaining enlightenment. Paintings and sculptures of Amitabha escorting the souls of the recently deceased to his private realm were among the most widely produced images in China from the twelfth to the fourteenth century. See the next image for another example.

Buddha Amitabha Descending from His Pure Land, late 13th century, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 41 1/8 x 21 1/8 in. (104.5 x 53.7 cm); Overall with mounting: 71 1/2 x 28 1/4 in. (181.6 x 71.8 cm); Overall with knobs: 71 1/2 x 30 3/8 in. (181.6 x 77.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1987 (1987.148)

The imagery in this painting shows the Buddha Amitabha descending from his Pure Land to welcome the soul of a recently deceased individual into his paradisiacal abode. Amitabha is one of several Buddhas who create and maintain such realms, and paintings of Amitabha (either alone or attended by bodhisattvas) were among the most widely produced images in China from the twelfth to the fourteenth century. See the previous image for another example.

Here, the Buddha stands on two lotuses and holds his right hand in a gesture of welcome. He wears a green undergarment with a wide hem decorated with floral patterns, and a red monastic shawl with gold bands. The abstracted folds of drapery on the right arm, the transparency of the green garment as it falls over the arm, and the figure's bean-shaped face are characteristic of the thirteenth century.

Arhat (Luohan), mid-14th century; Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Northern China. Wood with traces of pigment; Overall: H. 38 9/16 in. (98 cm), W. 32 5/16 in. (82 cm), D. 16 15/16 in. (43 cm). Lent by Victoria and Albert Museum

Although they are mentioned in early Buddhist writing, arhats—or luohans, as they are known in Chinese—do not appear in the visual arts of India and Southeast Asia. Their presence in Chinese art can be traced to a text brought to China in the seventh century by the famous pilgrim Xuanzang (about 602–664). After the twelfth century, arhats were among the most important icons in China. They appear most frequently in the guise of monks (with either Han Chinese or foreign features) and often in idyllic, remote settings.

In this example, the careful rendering of the figure's voluminous robes and of the rocky ledge upon which he sits are characteristic of Yuan-period treatments of the subject, as is his slightly twisting posture.

Unidentified Artist, Arhat (Luohan), late 13th–14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 44 1/4 x 19 5/16 in. (112.4 x 49.1 cm); Overall with mounting: 78 x 20 3/8 in. (198.1 x 51.8 cm); Overall with knobs: 78 x 22 in. (198.1 x 55.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Seymour Fund and Bequest of Dorothy Graham Bennett, 1984 (1984.226)

Fourteenth-century renderings of arhats (or luohans), particularly from the second half of that period, are imbued with an intensity that differs markedly from the more serene representations of these figures that dominated the centuries before. See the previous image for another fourteenth-century rendering of an arhat.

In this powerful painting, a bearded arhat stands in an undefined space holding a begging bowl that has miraculously filled with flowers. He gazes intently at the bowl, apparently unaware of the wind that is causing his robes to flutter. The broad, bare chest is unusual and may be another example of Indo-Himalayan influence on Chinese art of the fourteenth century. A similar disregard for clothing and a dramatic posturing are often found in representations of mahasiddhas, the unorthodox and quasi-historical Indian figures who helped spur the development of Esoteric Buddhist traditions from the seventh through the twelfth century.

Mahakala of the Tent, late 13th–early 14th century, Tibet. Limestone; H. 8 in. (20.3 cm), W. 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm), D. 2 in. (5.1 cm). Lent by The Kronos Collections

It seems likely that small stone sculptures of this sort were produced in Tibet for use there and for distribution throughout China. Mahakala is one of the terrifying protectors of later Buddhism. This manifestation, known as Mahakala of the Tent, was the tutelary deity of Khubilai Khan and of particular importance in China during the Yuan dynasty.

In this form, Mahakala has two arms and two legs and holds a skull cup, a knife, and a large staff (his principal attribute). The birds, dog, and wolf surrounding Mahakala are understood as his messengers, and he is flanked by four other figures that serve as his attendants.

Cosmological Mandala with Mount Meru, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Silk tapestry (kesi); Overall: 33 x 33 in. (83.8 x 83.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Fletcher Fund and Joseph E. Hotung and Michael and Danielle Rosenberg Gifts, 1989 (1989.140)

This elaborate mandala, or cosmic diagram, illustrates the Indian imagery that was introduced into China in conjunction with the advent of Esoteric Buddhism. This mandala centers on the mythological Mount Meru, represented as a pyramid topped by a lotus, the Buddhist symbol of purity. The sacred mountain stands in a swirling pool of water at the center of a tiered platform. Traditional Chinese symbols for the sun (a crow) and moon (a rabbit) appear at the base of the mountain.

The landscape vignettes placed at the four cardinal directions represent the four continents of Indian mythology. However, they follow the conventions of Chinese-style "blue-and-green" landscapes, with mountains and small buildings. The dense floral border derives from contemporaneous imagery from central Tibet, particularly from monasteries that had close ties to the Mongol court. The shape of the large initiation vases filled with lotus flowers parallels those of vessels used today in both Nepal and Tibet.

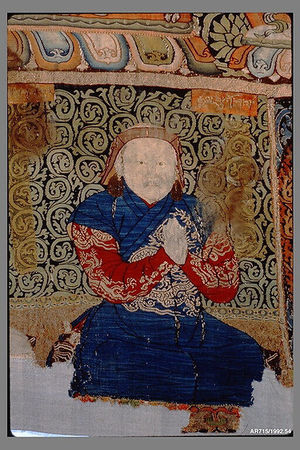

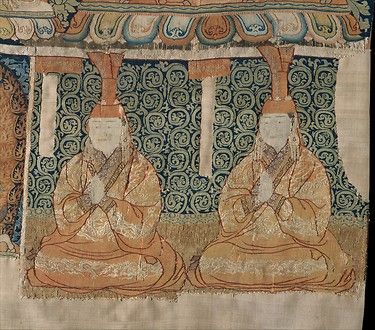

Mandala of Yamantaka-Vajrabhairava, ca. 1330–32, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Silk tapestry (kesi); Overall: 96 5/8 x 82 5/16 in. (245.5 x 209 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1992 (1992.54)

Central Asian tapestry-weaving techniques and Indo-Himalayan imagery are here combined to stunning effect in this spectacular mandala, which was most likely used during an initiation ceremony at court. The donors at the bottom left are identified by Tibetan inscriptions as two of Khubilai Khan's great-grandsons: Tugh Temür, who reigned twice as emperor between 1328 and 1332, and his brother Khoshila, who reigned briefly in 1329. Their respective spouses are shown at the far right. This combination of individuals helps date the work to the period between 1330 and 1332.

The tapestry belongs to an Indo-Himalayan tradition of palace-architecture mandalas in which the principal deity, in this case Yamantaka-Vajrabhairava, stands in a circle within a square with gateways at the four cardinal directions and further enclosed by three additional rings. Yamantaka, shown with the head of a bull, conquers Yama, the Lord of Death, and by extension transcends death entirely. Like all terrifying protectors, Yamantaka takes many manifestations, a reflection of his enormous power. In this manifestation, he also embodies the powers of Vajrabhairava, who has the ability to spur destruction and thereby renewal.

Daoism

Daoism, an indigenous philosophy and polytheistic religion deeply rooted in Chinese culture, proved useful to the pantheistic Mongols in promoting their intention to rule. Ritual and the quest for immortality—the foundations of Daoist practice—appealed to the shamanistic nomads. The existing orders, which had a strong following, provided vehicles for controlling large segments of the population. The Mongol emperors supported different orders at different times, according to their needs. During periods of political turmoil, both Daoists and Confucian literati sought refuge in Daoist (and Buddhist) temples.

Daoist art from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries reveals an intriguing account of the religious and social environment of Yuan China. During this period, Buddhist and Confucian ideas were incorporated into Daoism as part of a mutual interchange between the two traditions. All these connections are reflected in the visual arts. Daoist adepts and adherents, as expected, created Daoist art, but court artists, artisans, and workshops also received commissions to produce Daoist material. Those involved in making this type of art brought various artistic traditions to their projects, and thus stylistic distinctions often blur and iconographies overlap.

Daoist Figure, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Porcelain (Qingbai ware); H. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm); Pedestal: H. 3/16 in. (8.8 cm), W. 3 5/16 in. (8.4 cm). Lent by Jiangxi Provincial Museum

A large number of porcelain statuettes of Daoist and Buddhist figures were made during the Yuan period, but their iconography was not standardized. For example, this piece represents a Daoist, but he holds a lotus pod, which is not commonly associated with Daoism. He is accompanied by a doe (or dog) and a large bird (a crane), and he stands on a rock—a component more usually seen in representations of Buddhist luohans. Made of pure white clay that is only partially glazed, the figure was found not far from Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, where most of these objects were produced. They were not made solely for domestic consumption. In fact, some of the finest pieces have been found intact at archaeological sites in Luzon, the Philippines.

Jar with Eight Daoist Immortals, ca. 1350, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Porcelain with mold-impressed relief decoration (Longquan ware); H. 10 in. (25.4 cm), Diam. (body) 7 in. (17.8 cm). Lent by Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. S. Emlen Stokes, 1964

The subject of the Eight Immortals was a northern Daoist theme that emerged about the beginning of the thirteenth century. It was transmitted south in the fourteenth century together along with the northern predilection for three-dimensional imagery. This jar, produced at the Longquan kilns in southeast China, demonstrates both of these tendencies.

Nine Stars of the Northern Dipper, 13th century, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 44 5/16 x 21 5/16 in. (112.6 x 54.1 cm). Lent by Chikubushima Hôgon-ji

The nine stars of Beidou—one of the most important constellations in Daoism and believed to be the "ruler of human destiny"—are here represented in anthropomorphic form as seven androgynous figures gowned in white accompanied by two male figures dressed in red. Led by two heralds, the entire assembly appears as if descending upon a bank of clouds. Beidou was worshipped by the Southern Song imperial family as the god of personal fate. The painting, probably part of a ritual set and produced by workshops in Hangzhou or Ningbo, may have once hung in a temple devoted to Beidou. The treatment of the figures—namely their flat, idealized faces (which contribute to the semblance of divinity), stiff, upright postures, and seemingly unmoved garments—dates the painting to the thirteenth century, during the Southern Song dynasty.

Wu Daozi (Chinese, 689–after 755), Officials of Water, Heaven, and Earth, late 12th–13th century, Jin dynasty (1115–1234)–Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Three paintings mounted as panels; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image (each framed panel): 49 7/16 x 22 in. (125.5 x 55.9 cm); Overall (each): 90 3/4 x 30 3/8 in. (230.5 x 77.2 cm). Lent by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Special Chinese and Japanese Fund, 12.880, 12.881, 12.882

The Daoist pantheon comprises a complicated celestial bureaucracy that includes the Three Offices of Water, Heaven, and Earth—administrative units that govern the netherworld and determine the fate of sinners and petitioners. The style and, to some extent, the iconography—in particular the foliate clouds, ample use of gold, and dynamic entourage in the leftmost painting—recall murals in the northern Buddhist Yanshan Temple. The paintings presumably formed a ritual set, with the Official of Heaven at the center, his primacy supported by the inward-facing movement of figures from the flanking paintings. The composition is further established by certain contrapuntal elements, such as the thunder guards in the upper left of the Official of Water (left) echoing the group of demons led by the demon-queller Zhong Kui at the lower right of the Official of Earth (right).

Wu Rui (Chinese, 1298–1355), Laozi Conferring the Scripture of the Dao and the De, calligraphy dated 1335, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Handscroll; ink on paper; Image: 9 3/4 x 46 5/16 in. (24.8 x 117.7 cm); Calligraphy: 9 3/4 in. x 13 ft. 1 3/4 in. (24.8 x 400.7 cm); Overall with mounting: 12 5/8 x 25 ft. 7 1/16 in. (32 x 780 cm). Lent by The Palace Museum

Laozi, the legendary founder of Daoism, is seated on a shan (coach) accompanied by an attendant, who holds what is assumed to be the Daodejing (Classic of the Way and Virtue), purportedly written by Laozi. The figure in the pose of a petitioner might be Yinxi, the guard of the Hanggu Pass, about to receive the sage's legacy. Painted in baimiao (ink outline) style and jiehua (architectural) technique—both popular at the Mongol court, especially under the emperor Renzong—perhaps by a court painter, the work recalls northern woodblock prints in its stark contrast of ink tones.The terrace fringe recalls Daoist scenes on northern Cizhou ceramic pillows.

Mounted with the painting is a version of the Daodejing written in clerical script by the famous Yuan calligrapher Wu Rui. Clerical script experienced a revival during the Yuan dynasty, and Wu excelled in this particular type. The composition of the painting in front of a written text is typical for Daoist scriptures and also similar to Buddhist sutras with a frontispiece.

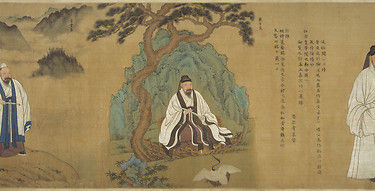

Unidentified Artist, Fourteen Portraits of the Daoist Wu Quanjie (ca. 17th-century copy of a 14th-century original), Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) or later, China. Handscroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 20 3/8 in. x 27 ft. 4 11/16 in. (51.8 x 834.8 cm). Lent by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Mrs. Richard E. Danielson, 46.252

Wu Quanjie, probably the most influential Daoist dignitary of his time, was the second patriarch of the Xuanjiao (Mysterious Teaching), an order founded in 1287 by Khubilai Khan. Wu's southern origin and knowledge of Confucianism enabled him to mediate between the Mongol court and the southern literati, who lost their elite status under the Mongols.

During Wu's lifetime, seventeen single small portraits (xiao xiang) of him were painted. Complemented by laudatory inscriptions by famous Chinese literati, these portraits were later merged into single horizontal scrolls, of which the current work is a copy (three portraits are missing). Called "environmental portraits," the landscapes are infused with both Daoist and Confucian symbolism, as can be seen in the last portrait here, which features a universally significant pine tree, a waterfall (Daoist), and a zither, or qin (Confucian). The round bustlike portraits are known from Chan Buddhist portraiture beginning about 1300.

Yan Hui (Chinese, active late 13th–early 14th century), The Daoist Immortal Yunfang Initiating Lü Chunyang into the Secret of Immortality, ca. 1300, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 42 11/16 x 19 3/4 in. (108.5 x 50.1 cm) Overall with mounting: 81 11/16 x 25 1/4 in. (207.5 x 64.1 cm). Lent by MOA Museum of Art

The initiation of Lü Dongbin (Chunyang by Zhongli Quan (Yunfang), both of whom were patriarchs of the Quanzhen order, is here shown as a powerful spiritual encounter set against a voided background, which enhances the intensity of the moment. The image stands in marked contrast to the more reserved representation of this scene in the Yongle Temple, which is set in a landscape.

The scroll is attributed to Yan Hui, an artist known for his paintings and murals of Daoist and Buddhist subjects. Zhongli, with radiant blue eyes (a rarity in Chinese painting), stands as if poised to deliver an exhortation, raising his index finger as he hands over the secrets of immortality—indicated by the six characters on the scroll—to a deferential Lü. The soft, broad brushstrokes in the garments and delicate lines indicating hair and facial features recall conventions in Chan Buddhist paintings.

Unidentified Artist, Beggar-Singer with Hound, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 30 1/8 x 14 3/16 in. (76.5 x 36 cm). Lent by Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne

Seemingly female, the figure dons a patchwork dress with a lattice pattern, typically worn by stage actors. Shouldering a lute and holding a book, the beggar-singer seems to be rehearsing for a role in a play. The presence of a white dog with a bell around its neck suggests that the figure may be a Daoist immortal, for they were often depicted with such canine companions. This therefore may be a representation of the male actor Xu Jian (stage name Lan Caihe), who, while preparing for a performance, was initiated into immortality by Zhongli Quan and Lü Dongbin (see next image)

Theater was very popular during the Yuan dynasty, and so-called deliverance plays were also performed at temple sites, which featured stages. Replicas of stages with sculpted actors have been found in tombs of the Jin and Yuan dynasties. An example of a replica stage with sculpted actors is included in the exhibition

Unidentified Artist, The Daoist Immortal Lü Dongbin, late 13th or early 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 43 1/2 x 17 1/2 in. (110.5 x 44.4 cm); Overall with mounting: 73 x 18 1/2 in. (185.4 x 47 cm); Overall with knobs: 73 x 20 1/2 in. (185.4 x 52.1 cm). Lent by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 62-25

..Together with Zhongli Quan (Yunfang), a leader of the Eight Daoist Immortals, Lü Dongbin (Chunyang) is said to have lived during the Tang dynasty (618–907) and has been venerated since the Northern Song (960–1127). Initiated into immortality by Zhongli, Lü was revered as a patriarch of the northern Quanzhen order. The Yongle Temple, built in Shanxi Province and completed by 1262, was devoted to him.

The earliest representations of Lü purportedly depicted him as a slovenly dressed commoner with a disheveled beard, but he is portrayed here in his more typical guise of a scholar, wearing a beige gown and a type of hat now known as a Chunyang cap. This mode of representation, easily recognizable to devotees of Lü who sought to be immortalized by him, shows the deity as lofty and self-confident, his hands gesturing in a manner similar to a Buddhist bodhisattva.

Fang Congyi (Chinese, ca. 1301–after 1378), Cloudy Mountains, second half of 14th century. Late Yuan (1271–1368)–early Ming (1368–1644) dynasty, China. Handscroll; ink and color on paper; Image: 10 3/8 x 57 in. (26.4 x 144.8 cm); Overall with mounting: 10 5/8 x 336 1/4 in. (27 x 854.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Purchase, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, by exchange, 1973 (1973.121.4)

A mountain range seems to dissolve into space, its silhouette like a dragon in bright mist. According to Daoist principles, the dragon (yang) must be balanced by its counterforce, the tiger (yin), which might be represented here by the dark patch of scrubby bushes that "confronts" the mountains along the right shoreline.

Here, the Zhengyi Daoist Fang Congyi deviates from the usual literati landscape style by creating optical distortions and shifting levels of focus, thus transforming the struggle of Dragon and Tiger (see next image) into an intellectual ideal abstracted from reality and liberated from representational constraints. The composition of the wide horizontal riverscape may reflect Zhang's encounter with northern paintings while visiting the capital Dadu.

Unidentified Artist, Dragon and Tiger, second half of the 13th century, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), China. Hanging scroll; ink on silk; Image: 57 x 38 1/4 in. (144.8 x 97.2 cm); Overall with mounting: 98 1/16 x 49 in. (249 x 124.5 cm). Lent by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, 11.6162

This ferocious contest between the two celestial animals of Daoism—the dragon and the tiger—is a rare representation of Daoist alchemy, the aim of which is to harmonize the contrasting principles of yang and yin. The importance of the dragon (or long, associated with fire, the east, and yang) and the tiger (or hu, associated with water, the west, and yin) is reiterated in the sacred mountain of Longhu Shan (Dragon and Tiger Mountain), in southeast China, home to the Order of the Celestial Masters. During the reign of Khubilai Khan, the prestige of the Celestial Masters reached new heights as Mongol imperial patronage shifted away from the northern Quanzhen to Longhu Shan.

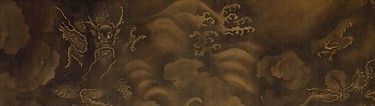

Zhang Yucai (Chinese, active 1295–1316),, Beneficent Rain, early 13th–14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Handscroll; ink on silk; Image: 10 9/16 in. x 8 ft. 11 in. (26.8 x 271.8 cm); Overall with mounting: 11 x 24 ft. 8 13/16 in. (27.9 x 753.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1985 (1985.227.2)

Zhang Yucai, the Thirty-eighth Celestial Master of Mount Longhu, was renowned for his paintings of bamboo and dragons. (It is only during the Yuan dynasty that Daoist worthies of such rank began to be recorded as artists.) Praised for his skills in bringing forth rain, he may have made this monumental scroll of four dragons—their bulging bodies vanishing into and emerging from the clouds and waves, their white eyeballs protruding from their heads—as part of a Daoist rainmaking ritual. Ink washes in a fine gray scale create effects of depth and light that contrast with the sharp white outlines of the dragons.

Bowl with Daoist Figures, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Jade; H. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm), W. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm), Diam. 4 1/16 in. (10.3 cm). Lent by The Cleveland Museum of Art. Anonymous Gift, 1952.510

Carved into the sides of this jade bowl is a scene showing a procession of Daoist immortals. Its pictorial style and the treatment of the figures' dress and accoutrements correspond to murals in thirteenth-century Daoist temples. Daoist immortals were thought to ride on clouds, as seen here in the two figures that make up the bowl's handles.

Chen Yuexi (Chinese, 14th century [?]), The Daoist Immortal Magu with a Crane and Flower Basket, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 40 3/8 x 21 7/16 in. (102.5 x 54.5 cm); Overall: 85 13/16 x 31 5/16 in. (218 x 79.5 cm). Lent by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection

The eternally youthful female immortal Magu is usually shown with her long hair tied in a knot, talonlike fingernails, and wearing the immortals' leaf-woven dress. She is here accompanied by a red-crowned crane; at her side is her attribute of a basket of herbs tied to a hoe. Particularly noteworthy is the episodic arrangement of the narrative, a convention seen in mural paintings in the Yongle Temple. The scenes in the upper corners, separated by bands of bluish clouds, may recount Magu's story as told by the fourth-century Daoist Ge Hong: having cultivated the Dao on the sacred mountain Guxu, she once appeared to the sound of drums and bells. The crane, whose beak points toward the episode at the upper right, may allude to Magu's journey to the immortal realms. The bold landscape elements in the style of the Northern Song painter Guo Xi (ca. 1000–ca. 1090) contrast with the delicate brushwork delineating Magu's face and dress, which emphasizes her shyness and modest appearance.

Chen Ruyan (Chinese, 1331–before 1371), View of the Mountains of the Immortals, second half of the 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Handscroll; ink and color on silk; Image: 13 3/4 x 40 1/2 in. (35 x 102.9 cm). Lent by The Cleveland Museum of Art. Bequest of Mrs. A. Dean Perry, 1997.95

Here, hidden among bizarre blue-green peaks dotted with pines, is a fantasy landscape where Daoist adherents, adepts, and auspicious animals together inhabit a utopian realm. Created as a birthday gift for a general involved in the struggle for power in the rebellion-torn late Yuan, the painting appears to be modeled after the Tang-dynasty painting Emperor Minghuang's Flight to Shu (Sichuan) (Smithsonian, Freer and Sackler Galleries; see image), which depicts the Tang emperor fleeing the capital during the period of political turmoil that led to the decline of that dynasty's fortune.

In an inscription on the painting, Ni Zan, an artist known for his austere images void of life, praises the scholar-painter Chen Ruyan for succeeding in "profoundly capturing the brush ideas" of Zhao Mengfu.

Pillow, late 13th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Pottery (Cizhou ware); L. 17 1/8 in. (43.5 cm). Lent by Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase

Hebei Province, where the Cizhou kilns were located, was an area where early Yuan drama flourished. Consequently, ceramic pillows made at Cizhou are often decorated with scenes from popular plays, many with Daoist themes. The scene on this pillow, which has not been conclusively identified, shows two supplicant officials in a garden before an emperor, who is attended by a military officer. The clouds behind the emperor figure suggest a Daoist association.

Other Religions

In addition to Buddhism and Daoism, a number of other religions were practiced in Yuan China. They were introduced by peoples of various faiths who came to China as traders or in the service of the Mongols. With the exception of Islam, these religions did not spread among the native population.

In the trading port of Quanzhou, on the South China coast, Indian traders built Hindu temples, fragments of which survive to this day. Followers of Islam produced steles and tombstones inscribed in Arabic.

Nestorian Christianity (spreading from Syria beginning in the fifth century) and Manichaeism (originating in Sasanid Persia) were known in China by the seventh century but retreated following a period of religious persecution in the mid-ninth century; they were later reintroduced by peoples of these faiths under the Mongols. While Nestorian objects can be found in Inner Mongolia and Quanzhou, there are few extant artifacts associated with Manichaeism, which is, however, known to have been practiced in Quanzhou and other port cities. In this exhibition are two rare paintings that appear to be Buddhist but have, through recent scholarship, been identified as Manichaean, demonstrating the syncretism common to Chinese religious belief.

Nestorian Cross with Handle, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Copper and wood; W. 4 3/4 in. (12 cm), L. 5 7/8 in. (15 cm). Lent by Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Museum

The shape of this cross, which was possibly intended for processional use, identifies it as Nestorian, one of several such crosses found in Inner Mongolia. The circular center with an S-shaped groove suggests the taiji diagram. Devised by Neo-Confucians in the Song dynasty and subsequently adopted by Daoists, the taiji became one of the most popular motifs in the religious and decorative arts of the Yuan period. It occurs at the center of the double vajra (thunderbolt) in Sino-Tibetan art of the Yuan and Ming periods, and also at the center of flowers on some blue-and-white porcelain pieces.

The Teaching of Manichaeism and Other Narratives, late 14th century, Yuan (1271–1368)–early Ming (1368–1644) dynasty, China. Hanging scroll mounted as a panel; ink, color, and gold on silk; Image: 56 x 23 5/16 in. (142.2 x 59.2 cm); Overall with mounting: 64 3/16 x 29 3/16 in. (163 x 74.2 cm). Lent by The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

This is one of a handful of Chinese paintings depicting Manichaean themes that recently have been identified in Japanese collections. Founded by the prophet Mani (about 216–276), Manichaeism was one of the many gnostic (esoteric wisdom) religions that flourished in West and Central Asia from the third to the seventh century. It was known in China beginning in the seventh century and may have been practiced, particularly in the south, until the seventeenth.

At the top of this painting, a Light Maiden, an important celestial being in Manichaean thought, is shown visiting a palatial realm, possibly a heaven. Beneath this scene, four devotees sit on either side of a sculpture, probably an image of Mani. The scenes of judgment in the lower half of the painting show the influence of Chinese Buddhist depictions of such realms, particularly the tortures of hell, which include a man being sawed in half, another shot with arrows, and a third crushed by a wheel.

Architectural Relief Depicting the Hindu Legend of Gajaranya Kshetra, 13th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Granite; H. 19 11/16 in. (50 cm), W. 27 15/16 in. (71 cm), D. 6 15/16 in. (17.7 cm), Wt. 352 3/4 lbs. (160 kg). Lent by Quanzhou Maritime Museum

This relief bears witness to a now-lost temple dedicated to Shiva, possibly the one referred to in the 1281 Tamil inscription also recovered in Quanzhou. The scene's iconography is South Indian, while the style of sculpting reveals the hand of a Chinese artist. It depicts the legend of the elephant who worshipped the Shiva linga each day with leaves shaken from a tree and water from the nearby Kaveri River. A spider spun a web over the linga (also as an act of devotion), inadvertently preventing the leaves from falling onto the sculpture. In the angry exchange that followed, both creatures died, only to be reincarnated by Shiva for their devotion.

This legend is closely associated with Tamil Nadu in South India, and its depiction on a Quanzhou Hindu temple provides a clue to the origins of the Indian merchants active in that city.

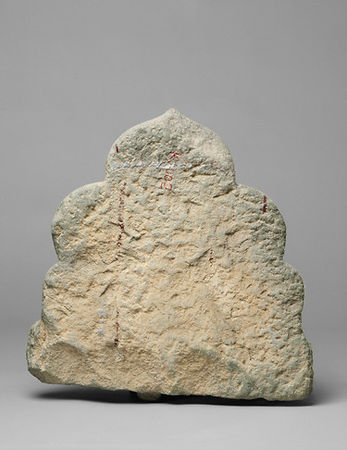

Nestorian Headstone with a Cross amid Clouds, probably 13th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Granite; H. 21 5/8 in. (55 cm), W. 20 1/16 in. (51 cm), D. 4 in. (10.1 cm), Wt. 110 1/4 lbs. (50 kg). Lent by Quanzhou Maritime Museum

Within the polytheistic climate fostered by the Mongol court, Christianity in Yuan China took two forms: the early Syrian Eastern (Nestorian) Church and the Roman Catholic Church. Christianity was not only tolerated but secured a privileged positioned in Mongol religious politics in 1204, when the Nestorian Christian woman Sorkaktani Peki, a Kerait Turk from Central Asia, married the son of Genghis Khan. As a result, Christians assumed a favored place at court and earned both the freedom to practice their faith and opportunities for high office.

This Nestorian tombstone displays a Greek cross as a symbol of the risen Christ, borne upon Chinese-style clouds—fitting imagery for a faith based on resurrection. This fusing of imported and local imagery is typical of the stylistic integration that was central to artistic expression in Mongol China.

Nestorian Headstone, probably 13th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Granite; H. 21 1/16 in. (53.5 cm), W. 20 1/16 in. (51 cm), D. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm), Wt. 99 1/4 lbs. (45 kg).. Lent by Quanzhou Maritime Museum

This Christian tombstone depicts a crowned and winged angel bearing a cross and dressed in Mongol fashion, including a lobed yunjian (cloud collar). The stele was discovered in 1975 in a district of Quanzhou once reserved for Christian and Muslim burial. A greater number of Nestorian gravestones than Roman Catholic examples have been recovered in and around Quanzhou, suggesting that the Syrian Eastern Church was more prevalent. A tombstone dated 1313, carved in the favored Syriac script, records the death of the Nestorian bishop of Quanzhou.

Nevertheless, the Church of Rome sent several papal missions to the Mongol court, including one to Yangzhou in 1294 led by the Franciscan monk John of Montecorvino. Another Franciscan, Andrew of Perugia, was appointed bishop of Quanzhou in 1323.

Jesus Christ as a Manichaean Prophet, 14th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Hanging scroll; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on silk; Image: 60 3/8 x 23 1/8 in. (153.4 x 58.7 cm). Lent by Tenmokusan Seiun-ji

This is one of a handful of Chinese paintings depicting Manichaean themes that recently have been identified in Japanese collections

The cross-legged posture of the figure in the center of this painting, along with the lotus pedestal, halo, and canopy, show strong parallels to contemporaneous Buddhist imagery. His white cloak and light red robe, however, differ from the Indic clothing usually worn by Buddhist deities. The figure can be identified as a representation of Jesus Christ in his role as a Manichaean prophet by the small gold cross that sits on the red lotus pedestal in his left hand.

Tombstone of the Mongol Official Daluhuachi, of Yongchun County, Fujian Province, ca. 13th century, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China. Granite; H. 17 5/16 in. (44 cm), W. 16 3/4 in. (42.5 cm), D. 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm), Wt. 44 lbs. (20 kg).. Lent by Quanzhou Maritime Museum

This stele is one of several bilingual examples found at Quanzhou. Arabic is used for religious passages, and Chinese provides the name and position or rank of the deceased. The Mongolian title daluhuachi was routinely assigned to ethnic Mongols serving as provincial officials in the Yuan administration. The Arabic inscription is from the Koran:

Everything is perishable, except His face. The Prophet (may peace be on Him) said: "Who so hath died a stranger hath died a martyr. He hath passed from this illusory world to Paradise and is in the good grace of Allah the most high."

The Chinese passage on the reverse translates as, "Grand Master for Admonishment, Yongchun County Official Dalu[huachi]," identifying the deceased as the county magistrate of Yongchun, Fujian. A survey of the Islamic tombstones recovered in and around Quanzhou has identified Muslims from across the Islamic diaspora, witness to the international connections enjoyed by this great port city of Mongol China.

"The world of Kubilai Khan" @ Metropolitan Museum New York, september 28, 2010 - january 2, 2011 www.metmuseum.org

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F64%2F119589%2F66215602_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F10%2F29%2F577050%2F66003091_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F85%2F94%2F119589%2F65290819_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F29%2F577050%2F65284774_o.jpg)