Sotheby’s Sells An Illustrated Folio From The Shahnameh for £7.4 Million Setting Auction Record For An Islamic Work of Art

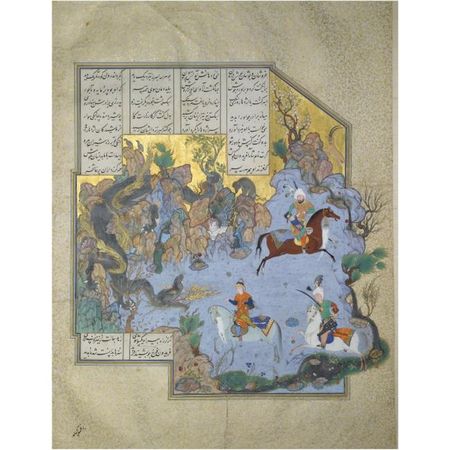

FARIDUN IN THE GUISE OF A DRAGON TESTS HIS SONS: ILLUSTRATED FOLIO FROM THE SHAHNAMEH OF SHAH TAHMASP, ATTRIBUTED TO AQA MIRAK, PERSIA, TABRIZ, ROYALATELIER, CIRCA 1525-35. Photo: Sotheby's

LONDON, WEDNESDAY, 6 APRIL, 2011 --- Today, Sotheby’s London established a new record for an Islamic work of art at auction when an illustrated folio from the Shahnameh made for Shah Tahmasp of Persia, universally acknowledged as one of the supreme illustrated manuscripts of any period or culture and among the greatest works of art in the world, sold for the outstanding and well above estimate sum of £7,433,250. This exceptional illustrated leaf saw competition for almost 10 minutes from no fewer than seven bidders, both in the saleroom and on the telephones, and finally sold for nearly four times pre-sale expectations to an anonymous bidder on the telephone (pre-sale estimate: £2-3 million).

Overall, Sotheby’s auction series brought £37,071,725 (60,612,270) establishing a record total for any Auction Series of Islamic Art ever staged. The Stuart Cary Welch Collection Part 1: Arts of the Islamic World realised the remarkable total of £20,909,750 ($34,187,441) – almost four times the pre-sale high estimate (est. £3.5-5.3 million) – achieving the highest-ever total for a single sale held in this collecting field. The auction established sell-through rates of 93.9% by lot and 99.9% by value. Of the lots sold, a notable 87% sold for sums in excess of their pre-sale high estimates. The biannual Arts of the Islamic World Sale also performed very well and achieved a total of £16,161,975 ($26,424,829), surpassing pre-sale expectations (est. £10.4-14.9million). The auction was 61.1% by lot and 83.9% by value.

Commenting on the results achieved for the Auction Series, Edward Gibbs, Senior Director and Head of Sotheby’s Middle East Department, said: “The sale of the Shahnameh leaf today represented a rare opportunity for institutional and private collectors of Islamic Art who competed from across the globe to acquire this unique work of extraordinary quality and beauty. The sum achieved of £7.4 million for the folio represents a new auction record in this collecting field. This extraordinary collection has generated tremendous excitement and interest along every step of its auction journey: from the announcement last November; to theexcitement and inter exhibitions in Doha and New York; and the catalogue; culminating in the extremely well-attended pre-sale view in London and the sale today which exceeded all expectations. The response from the collecting community and the quadruple-estimate total of £20.9 million is absolute testament to the passion and taste of the great scholar-connoisseur, Stuart Cary Welch, who assembled this remarkable collection.”

Edward Gibbs continued: “In this spring sales series Sotheby’s has established a new auction record for an Islamic work of art, and also set new benchmarks for an auction series of Islamic Art and a single sale of Islamic Art, clear evidence of expanding interest in this collecting field. We are now looking ahead to the Indian Art Sales in May, including the Stuart Cary Welch Collection Part 2: Arts of India, which is already hotly anticipated.”

FARIDUN IN THE GUISE OF A DRAGON TESTS HIS SONS: ILLUSTRATED FOLIO (F.42) FROM THE SHAHNAMEH OF SHAH TAHMASP, ATTRIBUTED TO AQA MIRAK, PERSIA, TABRIZ, ROYAL ATELIER, CIRCA 1525-35.

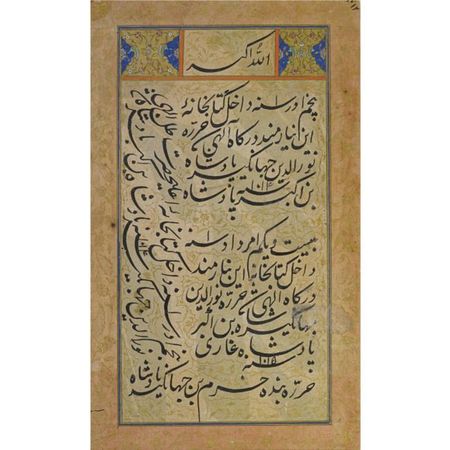

Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, text written in four columns of fine nasta'liq script, double intercolumnar rules in gold, wide gold-sprinkled margins, catchword at lower left corner; recto with a full page of nasta'liq text written in four columns and two headings written in white thuluth script within panels of fine illuminatio; folio 47.2 by 32cm. (18 5/8 by 12 5/8 in.) miniature: 29.7 by 28.5cm. (11 5/8 by 11¼in.). Estimate ,000,000—3,000,000 GBP. Lot Sold 7,433,250 GBP to an Anonymous.

PROVENANCE: Commissioned by the Safavid Emperor Shah Isma`il, circa 1522

Completed under the patronage of his son Shah Tahmasp at the royal atelier, Tabriz, circa 1525-1540

Presented in 1568 by Shah Tahmasp to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II

In the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild, Paris, 1903-1934

By Descent to Baron Maurice de Rothschild, Paris, 1934-1957

His estate 1957-1959

Arthur A. Houghton Jr., USA, 1959-1977

Agnews, London, 1977

EXHIBITED: Exposition d'art Islamique, Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris, 1903

A King's Book of Kings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1972

Wonders of the Age, The British Library, London; The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; and The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1979-80

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch 1972, pl.121-122, pp.120-123

Welch 1979, no.14, pp.62-63

Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.I, figs. 152-154, pp. 108-109, pl.13, vol. II, pl.29

Agnew 1981, p.182

Kevorkian and Sicre 1983, pp.154-5

Davis 2005, vol.1, pp.64, 70, 71, 84, 299

NOTE: The Shahnameh manuscript made for Shah Tahmasp of Persia (1514-1576, reigned 1524-76) is a monumental achievement of artistic skill and patronage, and a work of breathtaking quality and exquisite beauty. Containing the greatest epic of Persian literature, profusely and magnificently illustrated by the greatest artists and illuminators of the royal atelier over a period of two decades, it is universally acknowledged as one of the supreme illustrated manuscripts of any period or culture and among the greatest works of art in the world. It is rightly regarded as the apogee of Persia art. The complete manuscript contained 258 ravishing illustrations, countless panels of exquisite illumination and some 30,000 couplets of poetry written in crisp, rhythmic nasta'liq calligraphy on 759 folios of burnished and gold-sprinkled paper. It was executed between about 1520 and 1540, at a time when the Persian arts of the book had reached their absolute zenith. The provenance of this copy of the Shahnameh is one of the most glittering of any manuscript. It was commissioned by one emperor, Shah Isma`il, completed by another Shah Tahmasp, gifted to a third, Sultan Selim II of the Ottoman Empire, and was later owned by one of the great bibliophilic families of the modern era, the Barons de Rothschild, whose Western manuscripts included such masterpieces as the Belles Heures of the Duc de Berry and the Hours of Catherine of Cleves.

the history of the manuscript

The Shahnameh or 'Book of Kings' is the Persian national epic, telling the history and legends of Persia from prehistoric times down to the end of the Sassanian dynasty in the seventh century AD. The author, Firdausi (circa 933-1020), assumed the task of writing the history of the Persian kings in verse in 976 after Dakiki, a poet friend who had started the work, was murdered, Firdausi devoted the remainder of his working life to composing the 30,000 couplets of the Shahnameh. The finished text was presented to Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna in 1010 AD, 1001 years ago this year. The text was henceforth to become a touchstone of Iranian royalty, the text which, above all others, was to be revered by kings as confirmation of their sovereignty and as a symbol of their dynastic legitimacy. From the 14th century onwards no cultured prince could ignore the obligation to commission his own illustrated version of the national epic.

Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh was probably commissioned by his father, Shah Isma'il (reigned 1502-1524), the first Safavid Shah of Iran. Shah Ismail was a dynamic, charismatic and powerful character who conquered the ruling Aq-Qoyunlu Turkman and Uzbek tribes, creating an empire which encompassed a vast area from the Caucasus in the north-west to the Oxus river in the east and the shores of the Arabian Sea in the south. The new empire took in the most important cultural cities of the region - Herat, Shiraz, Qazwin and Tabriz, where he made the new Safavid capital. By 1522, the probable date of commissioning of the manuscript, Shah Isma'il had completed his conquests and was becoming interested in the arts. Shah Tahmasp, as a boy only eight years of age, had just returned to his father's capital from Herat where he had been child governor. Shah Isma'il died in 1524, respected and revered by the entire court, and Shah Tahmasp continued his father's passion for the arts of the book and specifically the production of this monumental copy of the Shahnameh, devoting the royal atelier to its preparation and production for a period of nearly two decades. Probably no other Persian work of art, save architecture, has involved such enormous expense or taken so much artists' time.

Shah Isma'il's conquests of different regions and cultural centres had enabled him to gather artists of different training and experience. It was this composite nature of the atelier that led to a new and glorious hybrid style of Persian miniature painting, now known as the Tabriz style. In his extensive researches on this manuscript and early Safavid painting, Welch identified two main source styles: the Timurid tradition of Herat and the Turkman tradition of Shiraz and other centres. At Shah Tahmasp's atelier older masters worked side by side with younger artists, encouraging the development of individual artists' skills and enhancing the performance of the atelier as a whole. The manuscript shows the remarkable range of Persian miniature painting of the period, all of an extraordinarily high standard.

It is difficult to conceive of the artistic magnitude of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp from our position in a different age and a different cultural tradition. There is no European equivalent of Shah Tahmasp's gathering of all the greatest artists of the era, along with the greatest scribes, illuminators, gilders, paper-makers, bookbinders and pigment-makers. But let us try to imagine a scenario in which the greatest patron of Renaissance Italy, perhaps Pope Julius II, gathered into one atelier the elite artists of the late 15th and early 16th century, both mature and young, along with their pupils, followers and workshops, and committed them to a single monumental project for a period of twenty years, during which time they worked on almost nothing else. The artistic goal of the Persian painter was book illustration. Western media such as fresco, panel or canvas did not feature in the Persian artistic tradition at this time. Therefore an Italian project of equivalent magnitude and significance would have to have been a national epic such as the Divine Comedy of Dante and to have included in one single, monumental and profusely illustrated volume the masterpieces of a host of Renaissance artists such as Leonardo, Bellini, Perugino, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, Titian, Corregio and more, and their pupils. Imagine such a manuscript, with 258 illustrations by artists of this calibre. It is an indigestible, almost surreal concept, and yet it is the inherent nature of this most glamorous of Persian manuscripts. Little surprise, therefore that Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh enjoys such an illustrious reputation.

The manuscript has no colophon, and the only date is inscribed on one of the miniatures – AH 934 (AD 1527-8), but the illuminated dedication on folio 16 states definitely that the manuscript was made for the library of Shah Tahmasp. A second manuscript prepared for Shah Tahmasp is the Khamseh of Nizami, now in the British Library, London, (Or.2265; Welch 1979, 134-183, and published in most of the same reference works as the Shahnameh). The Khamseh is of similar dimensions to the Shahnameh and is usually regarded as its sister manuscript. In its present condition it contains fourteen contemporary illustrations, painted within a shorter period circa 1539-1543, thus representing the Tabriz style in its full maturity. With their contemporary inscriptions and attributions, the miniatures of the Khamseh provide a basis for comparison and attribution of the Shahnameh miniatures.

The first leading artist of the Shahnameh, and the one to whom much of the initial stylistic innovation is credited, was Sultan Muhammad. It appears that for a middle period the leadership was taken over by Mir Musavvir, and that towards the end it was Aqa Mirak, the artist of the present folio, who dominated the project. The atelier must have occupied at least fifteen painters, identified as separate hands by Welch. Usually an illustrated page involved the work of more than one artist, perhaps a result of the way in which the studio was organised for manuscript making. Certain pictures are attributed to the hand of one artist working alone, and among these are some of the finest miniatures of the manuscript (including the present example). For our knowledge of the artists of Shah Tahmasp's atelier we are fortunate that near-contemporary Persian commentators wrote about them and the nature of their work. Dust Muhammad, himself an artist who worked on the Shahnameh to a limited extent, was commissioned by Prince Bahram Mirza, brother of Shah Tahmasp, to assemble an album of fine and representative paintings and calligraphy. In his preface to the album he gives an informative account of the works of past and present painters. Those of Shah Tahmasp's atelier were of course contemporaries of his whom he would have worked with and known personally. The album, with Dust Muhammad's nineteen-page text, is in the Topkapi Saray Library, Istanbul (H.1721). For a translation of much of this text see Binyon, Wilkinson and Gray 1933, pp. 183-188. A later, more extensive treatise, is that written by Qadi Ahmad circa A.D.1606, of which several manuscript copies are extant (Minorsky 1959).

After about 1540 Shah Tahmasp's interest in the arts waned, he became increasingly religious and was weighed down with political concerns. The threat of invasion by the Turks from the west had been a recurrent problem, settled by treaty in 1555. When Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent died in Hungary in 1566, there were fears in Tabriz that the treaty might not be upheld by his successor Sultan Selim II (r. 1566-1574). In 1567 a Safavid embassy led by Shah Quli left for Turkey and met with the Sultan at Edirne in February of 1568. The pomp of the occasion was noted by the Hapsburg embassy, then also present at the Ottoman court. There were thirty-four camels bearing the most magnificent gifts from Shah Tahmasp to the new Sultan. Top of the list of gifts and thus rated the most valuable, were two manuscripts, one a copy of the Qur'an said to have been written by the Imam Ali himself, the other a Shahnameh. Records show that this was indeed Shah Tahmasp's great volume. The Shahnameh stayed with the Ottomans for over three centuries, preserved in almost miraculous condition. Unlike the miniatures of so many Persian manuscripts, the compositions of the Shahnameh illustrations were not generally used or echoed in subsequent manuscripts. This could be partly because of their size and complexity, but also because the volume left Persia so soon, later artists had little access to it.

The manuscript left Istanbul about the end of the nineteenth century and reached France. By 1903 it was in the collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild who lent it for exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, where the catalogue description gave no hint of its magnificence. It was probably MS.17 in the Rothschild Library. It passed to Maurice de Rothschild in 1934 and after his death in 1957 it was one of a number of outstanding Rothschild books offered for sale, principally in America.

It was acquired by the collector and bibliophile Arthur A. Houghton Jr., benefactor of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. The volume was disbound so that separate pages could be exhibited - at the Grolier Club, the Pierpont Morgan Library and elsewhere. In 1971, 76 folios with 78 of the 258 illustrations were transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Further dispersals occurred over the next two decades, and in addition to those in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there are leaves of Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh in the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, The Freer/Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the David Collection, Copenhagen, the Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, the Aga Khan Museum Collection, the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran.

After the manuscript reached America Stuart Cary Welch embarked on a long and very thorough investigation and study of the manuscript, culminating in his great two-volume publication with Martin Bernard Dickson in 1981, The Houghton Shahnameh. It can safely be said that nobody has devoted as much time to the manuscript since circa 1540, while it goes without saying that the bulk of the information given here is derived from the published fruits of that study. The following works in the bibliography contain information on, or are devoted to Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh: Welch 1972; Welch 1976; Welch 1979; Dickson and Welch 1981; Welch 1985; Soudavar 1992, Melikian-Chirvani 2007, Brend and Melville 2010.

the episode illustrated on folio 42V

The scene depicted on the present folio occurs during the reign of the legendary king Faridun. The following descriptions and translations are taken from Welch 1972, p.120, and Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.2, no.29.

"Upon the death of Zahhak, Faridun reigned supreme, dispensing justice by binding evil hands with kindness. Mankind turned once again to God, and the world became a paradise. After fifty years Faridun had three sons, tall as cypresses, swift and powerful as elephants, and with cheeks like spring. In his love for them Faridun refused to tempt fate by assigning them names. When they came of marriageable age, he sought them suitable wives. Through the services of an emissary, he discovered three pearl-like princesses, daughters of King Sarv of Yemen. The nameless sons journeyed to Yemen, married the girls, and brought them home. They were met by a dragon: Faridun in disguise"

"News came of their return: without delay

King Feraydun set out to block their way.

He longed to know their hearts, and by a test

Lay all his mind's anxieties to rest.

He took a dragon's form, one so immense

you'd say a lion would have no defence

Against its strength; and from its jaws there came

A roaring river of incessant flame.

He saw his sons; dust rose into the sky,

The world re-echoed with his grisly cry.

First he attacked the eldest prince, who said,

"No wise man fights with dragon foes", and fled.

Seeing his second son, he wheeled around.

The youth bent back his bow and stood his ground,

Shouting, "If combat's needed I can fight

A roaring lion or an armoured knight."

Lastly the youngest son approached and cried,

"Out of our path, fell monster, step aside.

If you have heard of Feraydun, then know

That we're his valiant, lion-like sons, now go,

Or I'll give you a crown that you'll regret!"

He saw how each son took the test he's set

And disappeared. He left them there, but then

Came out to greet his princes once again-

Their king now, and the father whom they knew,

Surrounded by his royal retinue."

the artist

Aqa Mirak was one of the leading royal artists of Shah Tahmasp's reign and is thought to have been the director of the atelier during the later years of the production of this manuscript. Many of the illustrations in his crisp, clear style, with a vibrant palette and relatively large figures, are to be found in the later pages of the Shahnameh.

He was a man of diverse abilities who, in addition to his work as an illustrator of manuscripts, devoted time to the decoration of mosques and palaces. He had special skills as a colourist and preparer of pigments, skills which can be seen to have contributed to the peculiar lightness and clarity of his miniatures. He was a close companion of Shah Tahmasp himself and contemporary sources indicate how highly he was regarded by his fellow artists. Welch gives a lengthy and perceptive account of Aqa Mirak in volume I of the 1981 publication The Houghton Shahnameh (pp.95-117). Therein we discover that Dust Muhammad, another of the artists of the royal atelier, describes Aqa Mirak thus:

"the surety of the community of Sayyids, the genius of the age, the prodigy of our era.....the Heir to the Khans....among those privileged to approach the Shah....At the House of Painting he but picks up his brush and depicts for us pictures of unparalleled delight. As for likenesses - and where are their like? – as the farseeing view them, they are foremost in sight. God grant him his pictures and paintings! Good Lord! The glory of this painter! What God-given might!"

(Dickson and Welch, Vol.I, p.95)

Sam Mirza, another of his contemporaries, describes him as "a genius of the age, as peerless in designing as in painting.....the guiding spirit of the corps [of artists]." (ibid. p.95).

Finally, Qutb al-Din, writing in 1556-7, describes him as "the peerless paragon for the host of means and the myriad modes employed in this art...".

Welch suggests that such was his reputation amongst his fellow artists and his patron that he was given the honour of painting the first illustration in this copy of the Shahnameh, the scene of Firdausi and the Court Poets of Ghazna, on folio 7, and some of his most dramatic and fully expressed works appear in the first part of the manuscript, including the present painting (folio 42). Welch suggests that although these two folios illustrate early episodes in the Shahnameh, they are works of Aqa Mirak's mature phase, and he compares their style and execution with the artist's work for the royal copy of the Khamseh of Nizami of 1539-43 (British Library, Or. 2265). Aqa Mirak's career continued after the decline of Shah Tahmasp's interest in painting in the 1550s, and he subsequently painted for Prince Ibrahim Mirza.

In his discussion of Aqa Mirak, Welch described the present illustration of Faridun in the Guise of a Dragon Tests His Sons as follows:

"The style of Aqa Mirak's last picture for the Shahnameh, Faridun, in the Guise of a Dragon, Tests His Sons, is identical to that of his work in the Nizami of 1539-43. More subdued in palette than his other pictures for the Houghton manuscript, it suggests dusk, or an overcast day. Having overcome all technical problems as well as his own inhibitions, the artist could tell his story more directly, to greater effect, and with livelier expressiveness. He had learned that he could understate. Although earlier Aqa Mirak could not always hold our interest, even with maximum exertion, now he can captivate with a nuance. In composition, Faridun Tests His Sons is like the finest watch, possessed of the softest tick and the least evident works; we barely sense the sinews and muscles that bind the picture together. Although the master has set himself a forbidding task, we are no longer perturbed by the strain of his thought. The dragon's springing silver, black and gold body is echoed by the delicately sinuous cascade, which broadens into a stream as it falls and ultimately leads us back into the foreground, terminating at the feet of the cringing rabbit. Thus, our eye pursues a continuous circle of delight, from stream to dragon and round again. Spatially, too, Aqa Mirak has achieved mastery. Foreground and background are clearly demarcated, even though the work is free of illusionism. We have met Faridun's three sons elsewhere:.... The painter has infused all three faces with personality – they seem portraits rather than types. The faces in the rocks are psychologically interesting, rivalling or even surpassing Sultan Muhammad, and suggesting that this picture is Aqa Mirak's reply to the great Gayumars."

(Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.I, p.108)

Cary Welch's handwritten notes on the backboard of the frame are as follows:

"First sight of this while showing ms. to A.A.H.JR [Arthur A. Houghton Jr] at Rosenberg and Stiebel's salesroom on 57th St. in NYC. Amazed by its quality."

"Enjoyment of photographing and studying it, as well as writing about it"

": seeing it on the sunlit white wall near the door to the dining room of the Wye Plantation [Houghton's estate in Maryland] – it was one of many (35?) pictures from the Shahnameh so shown, fortunately not for very long."

"Finding out from Agnews that this was one of the folios being offered for sale."

"acquiring it: the costliest acquisition I had ever made. Terrible effort, but successful (a Triumph!) – "

Top-Selling Lots in the Stuart Cary Welch Collection Part 1: Arts of the Islamic World:

Another important highlight of today’s auction was Five Holy Men, attributed to Govardhan, from Mughal India, circa 1625-30, one of the most brilliant, arresting and memorable of Mughal miniatures. A masterpiece of Mughal portraiture, it typifies the work of Govarhan at the height of his powers aroundmasterpiece of Mughal portraiture, it typifies the work of Govarhan at the height of his powers around 1630. The folio was acquired by a telephone bidder for the 9-times estimate sum of £2,600,000 (est.£200,000-300,000).

FIVE HOLY MEN, ATTRIBUTABLE TO GOVARDHAN, INDIA, MUGHAL, CIRCA 1625-30, A LEAF FROM THE ST. PETERSBURG ALBUM, BORDERS SIGNED BY MUHAMMAD HADI AND DATED 1172 AH/1758-9 AD. Photo Sotheby's

Opaque watercolour on paper, mounted on an album leaf from the St.Petersburg Album, with wide cream borders decorated in gold; reverse with a large panel of nasta'liq calligraphy and wide borders of blue paper illuminated with gold scrolling floral motifs, the border of the reverse signed at lower right by Muhammad Hadi and dated 1172/1758-9; miniature: 24.1 by 15.2 cm. (9.5 by 6in.) folio: 49 by 33 cm. (19 by 13in.). Estimate 200,000—300,000 GBP. Lot Sold 2,953,250 GBP to an Anonymous

PROVENANCE: Joseph Soustiel (1904-1990), Paris.

EXHIBITED: A Flower from Every Meadow, The Asia House Gallery, New York; The Center of Asian Art and Culture: The Avery Brundage Collection, San Francisco; and The Albright-Knox Gallery of Art, Buffalo, New York, 1973

Paintings from the Muslim Courts of India, British Musuem, London, 1976

The Grand Mogul, Imperial Painting in India 1600-1660, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, 1978

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch 1973, no.63, pp.104-105

London 1976b, no.132, p.74

Beach 1978, no.41, pp.120-121

Welch 1978b, pl.24, pp.86-87

Honour and Fleming 1982, p.548, pl.12.56

Welch 1995, no.12, p.336

Habsburg et al. 1996, facsimile volume pl.231, text volume, p.124, no.231, and p.141, pl.231

NOTE: This is one of the most brilliant, arresting and memorable of Mughal miniatures. A masterpiece of painting, mood and spirituality, it typifies the work of Govardhan at the height of his powers around 1630, a period when Milo Beach has described him as working at "an extreme of refinement" (Beach 1978, p.119). Okada describes him as "taking portraiture to its zenith, making him the most penetrating and remarkable portraitist in the imperial atelier."(Okada 1992, p.203)

Govardhan was born at court, a "house-born" son of the artist Bawani Das. His earliest works were illustrations for manuscripts at the end of Akbar's reign in the early years of the 17th century, but his separately produced works show an immediate interest in portraiture, both single figures and groups. He continued in the royal atelier through Jahangir's and Shah Jahan's reigns. He produced grand and majestic royal portraits, but his favourite theme was holy men, an interest inherited perhaps from his master Basawan. Govardhan took this genre to new heights, with paintings of penetrating and profound insight, of power and subtlety, which, combined with breathtaking technique, produced paintings of extraordinary intensity. "The stunning portrait gallery of Hindu and Muslim holy men is probably Govardhan's major contribution to the history of Mughal painting" (Okada 1992, p.196).

In the present painting Govardhan depicts five holy men seated in meditative contemplation beneath a tree with a temple in the background on the right and a townscape in the distance. Cary Welch recognised the setting as being near an early Kashmiri temple close to Srinagar (see Hapsburg et al. 1996, text volume, p.124). With his characteristic use of muted tones, atmospheric skyscapes and extraordinary skills of portraiture, Govardhan has imbued the scene with a sense of profound realism and sympathy that must stem at least in part from his having studied a group of ascetics like this from life. Each of the waking figures appears to be in a state of trance, lost in their own worlds of meditation. Yet despite their isolation from the cares of the material world, the figure on the left stares straight out at the viewer, drawing us into direct interaction with their scene and their spiritual states.

Although the subject and mood of the painting are very Indian, there are elements which show the influence of, and Govardhan's understanding of, western art, gleaned through the presence in India of numerous European engravings. The distant townscape is one such element, which had become a regular motif in Mughal painting by the time Govardhan painted this scene, but there is another, more subtle example. As early as 1978 Cary Welch had suggested that the figure of the young mystic lying across the foreground might have been inspired by a European print. By 1996 Gauvin Bailey had identified the source as the female figure in the foreground of St Chrysostomus by Barthel Beham (1502-40), a German artist and engraver who was employed at Nuremberg and at the court of Wilhelm IV of Bavaria (see Hapsburg et al. 1996, p.125; several copies of this engraving are in the British Museum and can be seen on their website).

Govardhan had a close relationship with Prince Dara Shikoh, Emperor Shah Jahan's eldest son and heir apparent to the Mughal throne. Both patron and artist had an interest in mysticism and it has been suggested that some of Govardhan's studies of ascetics might have been executed at the behest of the Prince (Welch 1985, p.243, 244; Okada 1992, p.196).

Cary Welch catalogued this painting three times, in 1973 for his exhibiton A Flower from every Meadow, in 1978 for his book "Imperial Mughal Painting" and for the text volume of the facsimile edition of the St. Petersburg Muraqqa. The following are quotations from his eloquent descriptions:

"Govardhan's miniature brings to life five Hindu holy men meditating beneath a neem tree near a Kashmiri temple close to Srinagar, seen in the background.

Each portrait represents a stage of life. In the foreground, a languid youth with a golden sea of curls reclines opposite the figure, a middle-aged sanyasi whose other-worldly gaze, self-grown shawl of long hair, and claw-like fingernails attest to his shedding of almost every mundane activity.

To his left sits an older devotee, whose expressive, disciplined face implies both intellectual power and spiritual grace. At the left of the miniature, momentarily distracted from his elevated state, a dark-bearded figure with a mala (rosary) and a turban wound from his own hair, looks out beyond the frame. Behind the others reclines a holy man whose tense expression hints of troubled dreams. In the foreground, a fire smoulders, producing both warmth and the ashes worn instead of clothing by these aspiring saints." (Hapsburg et al. 1996, pp.124-5).

"His favourite palette is the golden-tan and gray one shown here, where it is keyed to the subject by the dung fire and the ash covered figures. As an artist, he invites comparison to Basawan and Daulat, who shared his spiritually uplifting Rembrandtesque world of softly rounded, almost liquid forms and soulfully picturesque portraiture" (Welch 1978b, p.87)

In the 18th century the painting was mounted in an Imperial Persian album known as the St. Petersburg Album. The album was assembled in Persia in the 1740s and 1750s, with a large number of Mughal, Deccani and Persian paintings of exceptional quality and importance. The majority of the Mughal and Deccani miniatures in the album had been brought back to Persia from the royal Kitabkhaneh in Delhi after Nadir Shah's invasion of India and sacking of Delhi in 1738-9. In the 1740s and 1750s, in the manner of the great Imperial albums made for Jahangir and Shah Jahan, the Mughal and Deccani miniatures were assembled, along with a smaller number of important and rare late Safavid works, into an album of very large proportions. As was the style in such albums, each folio had a miniature on one side and calligraphy on the other, so that when the pages of the album were turned, the miniatures would be opposite miniatures, and the calligraphy opposite calligraphy. Many of the calligraphic specimens were in the hand of the famous Safavid calligrapher Mir Imad al-Hassani (d.1615). The borders were decorated in gold by two leading artists of the day, Muhammad Hadi and Muhammad Baqir. In the present case the gold illumination on the blue borders on the verso have been signed by Muhammad Hadi and dated 1172/1758-9.

The majority of the extant folios from this album are in the Oriental Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg. The album has been published in facsimile form by Hapsburg et al. (1996). At least thirty folios were separated and dispersed during the 18th or 19th century and are in various museum collections including the Freer/Sackler Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Insititution, Washington D.C., the Musée du Louvre, Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, the Art Institute of Chigaco, the Aga Khan Museum Collection (formerly the Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Collection) and the Fondation Custodia, Paris. For further accounts of this album and other separate leaves see Robinson 1967, nos.88, 91 and 94; Beach 1978, p.77 and as indexed; Lowry and Beach 1988, p.294, no.345.

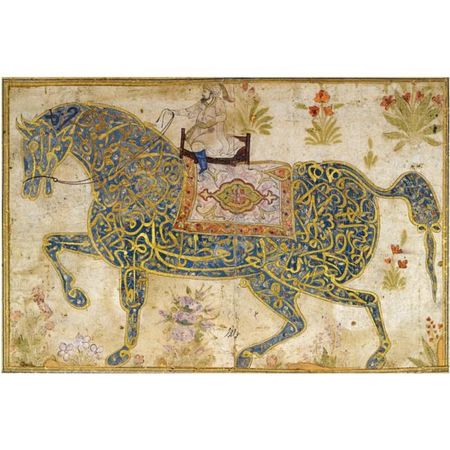

A further top lot, The Throne Verse (Ayat-Al-Kursi) in the Form of a Calligraphic Horse, India, Deccan, Bijapur, circa 1600 exemplifies the art of calligraphy at its most accomplished. The artist has written the entire Throne Verse, one of the most popular verses in the Qur’an, forming the gold letters and words in an inventive and skilful manner into an elegantly prancing horse. This extraordinary technical achievement sold to a telephone bidder for £2,057,250 (lot 99, est. £20,000-30,000).

THE THRONE VERSE (AYAT AL-KURSI) IN THE FORM OF A CALLIGRAPHIC HORSE, INDIA, DECCAN, BIJAPUR, CIRCA 1600. Photo Sotheby's

Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 16.7 by 25.8cm. (6 5/8 by 10 1/8 in.). Estimate 20,000—30,000 GBP. Lot Sold 2,057,250 GBP to an Anonymous

PROVENANCE: Formerly in the Firouz Collection

EXHIBITED: Indian Drawings and Painted Sketches: 16th through 19th Centuries, The Asia House Gallery, New York, 1976

Calligraphy in the Arts of the Muslim World, The Asia Society, New York; the Cincinnati Art Museum; the Seattle Art Museum; the St. Louis Art Museum, 1979-80

Birds, Beasts and Calligraphy, Harvard Art Museums, 1981

Line and Space: Calligraphies from Medieval Islam, Harvard Art Museums, 1984

Inscription as Art in the World of Islam, Hofstra University, Hempstead, 1996

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch 1963c, p.31

Welch 1976, no.31, p.70

Welch A. 1979, no.77, pp.180-181

NOTE: This is a calligraphic masterpiece, displaying the art of calligraphy at its most accomplished. The artist has written the entire Throne Verse, one of the most popular verses in the Qur'an, forming the gold letters and words in an extraordinarily inventive and skillful manner into an elegantly prancing horse. The technical achievement is superb and the artistic achievement inspiring.

The text of the Throne Verse begins at the horse's head; the first half of the verse is written in the area in front of the saddle; the second half of the verse is written in the area behind the saddle, and the final words are spread across the area below the saddle from the hind quarters to just above the vertical front leg.

The text of the Throne Verse is as follows:

"Allah is He besides whom there is no god, the Ever-Living, the Self-Subsisting, by whom all subsist; slumber does not overtake Him nor sleep, whatever is in the heavens and whatever is in the earth is His; who is he that can intercede with Him but by His permission? He knows what is before them, and what is behind them, and they cannot comprehend anything out of His knowledge except what He pleases; His knowledge extends over the heavens and the earth, and the preservation of them both tires Him not, and He is the Most High, the Great."

(The Holy Qur-an, translated by Maulvi Muhammad Ali, Lahore, 1920)

In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Calligraphy in the Arts of the Muslim World, Anthony Welch discussed the possible symbolism of this calligraphic horse, suggesting that the mighty horse depicted here symbolises God's omnipotence and omniscience as described in the specific words of the Throne Verse, which carries the miniscule rider, so much smaller in scale than the horse, representing the human soul.

Other examples of pious calligraphic animals are known, but the majority are in the form of birds or lions (see, for instance, a lion made up of the words of the Nadi' Ali, in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, see Paris 2007, no.51, p.146). Horses are very much rarer, and the amount of text involved has produced amongst the most complex and dramatic examples known.

In the lower part of the saddle cloth, below the central lobed medallion, is the remnants of a signature of the artist. The only legible word is kamtarin and the rest is rubbed and illegible. Below the belly of the horse on the plain background is an inscription reading sahib indicating a past owner.

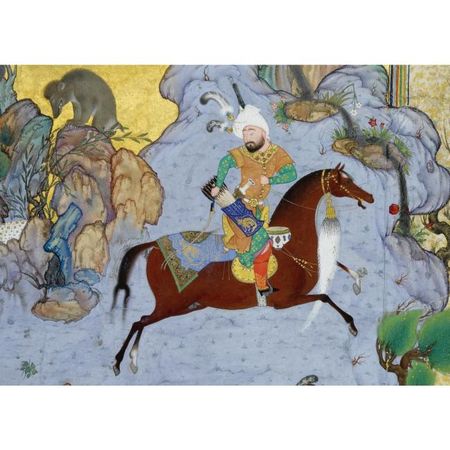

A striking painting of Sultan Ali Adil Shah II hunting a tiger sold to a buyer over the telephone for the sum of £ 1,138,850 against a pre-sale estimate of £60,000-80,000. This circa 1660 watercolour on paper is a rare example of Deccani courtly painting to have survived from the 16th and 17th centuries, as well as being one of the most glorious, rich and mesmerising of Deccani portraits. Showing both Iranian and Mughal influence, it depicts a radiant, and yet almost dreamlike Sultan as he looses his arrow towards a tiger crouching on the rocks in front of him.

SULTAN ALI ADIL II SHAH OF BIJAPUR HUNTING TIGER, INDIA, DECCAN, BIJAPUR, CIRCA 1660. Photo Sotheby's

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, mounted on an album page with borders of gold-sprinkled cream paper; miniature: 21.8 by 31.5cm. (8½ by 12 3/8 in.) album page: 31.1 by 43.3cm. (12¼ by 17 1/8 in.). Estimate 60,000—80,000 GBP. Lot Sold 1,138,850 GBP to an UK Private

PROVENANCE: Christie's, London, 24 April 1980, lot 55

EXHIBITED: India, Art and Culture 1300-1900, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Zebrowski 1983, no.110, p.142

Welch 1985, no.205, pp.306-7

Michell and Zebrowski 1999, fig.138, p.188

NOTE: This striking painting of Sultan Ali Adil Shah II hunting tiger is one of the most glorious, rich and mesmerising of Deccani portraits. Despite the fragmentary nature of the painting, it retains a majestic power and presence. Indeed, the loss of the lower part and corners almost enhances its impact, focussing the eye of the viewer on the glittering, radiant, almost dreamlike figure of the Sultan as he looses his arrow towards the tiger crouching on the rocks in front of him.

The paintings produced in the Deccani states of south central India present one of the most enigmatic and alluring cultural phenomena in the history of the Indian subcontinent. Mixing influence from outside traditions, such as those of Iran and the Mughal court, with an intense, idiosyncratic pictorial idiom, Deccani artists and patrons of the 16th and 17th century produced a distinctive style that was all their own, characterized by exquisite quality, accentuated forms and colours, lyricism, sensuousness, heat, languid romanticism and an almost dreamlike atmosphere that verges at times on the surreal, magnifying the technical virtuosity of the artists. It is an alluring and heady mix, drawing the viewer in and rewarding them with a sense of intimacy with the characters and landscapes that one rarely gets from the more formal Mughal style.

Zebrowski has attributed the present picture to an artist dubbed the Bombay painter, who was responsible for around eight known works (Zebrowski 1983, pp.139-144, fig.110). One of the paintings attributed to his hand bears an inscription naming the artist. Unfortunately it is rubbed and unclear, leaving the exact identity of this artist unconfirmed, but Zebrowski read it as either 'Abd al-Hamid naqqash' or 'amal-i Muhammad naqqash'.

In the present work it is worth noting the disproportion in size between the central, haloed figure of the Sultan, and the diminutive tiger, and there is surely a symbolic message in this, relating perhaps to the sultan's political and military conflicts with the Maratha chief Shivaji, which were at their height around 1660. Shivaji was a formidable enemy, and in the composition of this portrait, with the large, proud, confident, gold figure of the Sultan, the radiant halo round his head, and the small, crouching figure of the tiger, Ali Adil Shah was perhaps making a statement about his power and majesty, and his own legitimacy to rule in the face of Shivaji's threat.

The painting was exhibited in the monumental 1985 exhibition India, Art and Culture 1300-1900, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and in the accompanying catalogue Cary Welch described it in the following terms:

"As if in a glittering tableau vivant, Sultan Ali, resplendently dressed in gold, orange, and blue, smiles victoriously in his portrayal as a tiger hunter. The likeness is intensely Indian, bringing to mind gold coins of the Gupta dynasty in which deified heroes slay evil in the form of lions. His lips are stained red from chewing betel nut (pan), and his eyes are shaped like pipal leaves as he speeds a well-aimed royal shaft into the vitals of a beastly force of darkness – an inadequate surrogate for the encroaching enemy. The wicked tiger snarls from a rocky outcropping in which the artist has hidden amusingly dastardly grotesques. This heart of a miniature, the corners and lower section of which are missing, once included Ali's royal barge, of which only two finials remain. It was painted by the same hand as several wall-paintings – large bouquets of flowers in splendid vases adorned with gold and lapis lazuli arabesques – in the Athar Mahal (Palace of Relics). Despite the frustration of ruling a doomed state, Sultan Ali was an important and inventive patron" (Welch 1985, pp.306-7).

Cary Welch's handwritten notes on the backboard of the frame are as follows:

"Ali Adil shah II of Bijapur 1652-1672"

"Ali died Nov. 24, 1672. Succeeded by Sikanda, aged 4. (I.Sankar, Shivaji & his times p.192)"

"Ali came to throne at 15 in 1656 (D.C. Varma, History of Bijapur, P.30)."

"Quick swoop of eye and arrows -

Is gold in form of leaf? or pigment?"

"Pan-caked lips- "

"Leathery" pigment - built up like jewels or enamel. Bowstring & shaft of arrow politely disappear in front of face and feathery beard."

"Turban: lapis-lazuli, with canary yellow, 'slashes' of linen"

"Optimism, victory over tiger hardly parallelled in his struggle against Mughals."

"Rocks suggestive of grotesques."

"A damaged picture, lacking lower corners, which seems to have been remounted at Kishangarh, presumably the ruler of Kishangarh had captured it in Deccan during the 17th century. Other Deccan pictures known to have been at Kish. court."

A LEARNED MAN: ATTRIBUTED TO BASAWAN, INDIA, MUGHAL, CIRCA 1575-80, VERSO WITH CALLIGRAPHY IN SHAH JAHAN'S HAND.

Ink with colours on paper, mounted on an album page with finely illuminated borders; reverse with a panel of calligraphy in the hand of Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan) dated 1015/1605; drawing:12 by 11.2cm. (4¾ by 4 3/8 in.) inner borders: 21.7 by 13.4cm. (8½ by 5¼in.) calligraphy panel: 18.1 by 9.5cm. (7 1/8 by 3¾in.). Estimate 60,000—80,000 GBP. Lot Sold 881,250 GBP to an Anonymous.

PROVENANCE: Sotheby's, London, 15 June 1959, lot 126

Hagop Kevorkian Collection, New York

Sotheby's, London, 1 December 1969, lot 126

EXHIBITED: Indian Drawings and Painted Sketches: 16th through 19th Centuries, The Asia House Gallery, New York; the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge; the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, the Avery Brundage Collection, 1976

Indian Drawing, the Hayward Gallery, London; the Wolverhampton Art Gallery; the Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry; the Bolton Museum and Art Gallery; the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, 1983

Akbar's India: Art from the Mughal City of Victory, The Asia Society Galleries, New York; the Arthur M. Sackler Musuem, Harvard University Art Museums; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1985-1986

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch 1976, no.7, pp.34-35

Hodgkin and McInerney 1983, no.1

Brand and Lowry 1985, no.41, pp.79, 146-7

Brand 1987, fig.7.25, p.119

Verma 1994, no.118, p.92

NOTE: This is a superb portrait, attributable to one of the greatest Mughal artists at the height of his powers. It demonstrates extraordinary artistic skill, eclectic influences and thematic originality on a profound level.

It was part of an album assembled for Prince Khurram (later Shah Jahan, r. 1628-57) in 1611-12, and bears the prince's handwriting on the verso, on a panel of marbled paper, along with his signature "the slave Khurram ibn Jahangir Padshah". The inscriptions supply evidence that Prince Khurram was modelling his handwriting on that of his father Jahangir. Three library accession notes have been copied, one dated 1014/1605-6, appears to have been copied from Jahangir's accession note on the flyleaf of the Victoria and Albert Museum Akbarnama. Another, with the same date, is a slight variation of the same inscription, and the third is an accession note from another manuscript with the date 1015/1606-7 (see Sotheby's, London, 1 December 1969, p.61; Welch 1976, p.31, Brand and Lowry 1985, cat.41, pp.146-7).

The drawing has been attributed by Cary Welch and others to Basawan, circa 1575-80. The figure has been described most often as a Learned Man, but also as a Venerable Sufi and an Old Sufi. The portrait depicts a male figure of mature years and corpulent frame, rather concentratedly reading a book. He is shown seated on the floor, reclining against a cushion, with several objects and a cat around him. The drawing is executed in the nim-qalam technique, a technique that Basawan used to great effect in imitation of the grisaille manner of European engravings. The drawing is very expressive and psychologically acute, with great attention paid to volume and spatial aspects.

Basawan was one of the greatest masters of the imperial Mughal atelier. Original, technically immensely skilful, acute in observation and profound in expression, his many works show a sense of artistic confidence, individuality and talent that was supreme in its day. Amina Okada described him as "one of the greatest artists of his time and the most accomplished painter at Akbar's court. His original and eminently personal style, receptive to the pictorial lessons bequeathed by Western art and nourished by subtly assimilated Persian references, characterizes Akbari art at its apogee – eclectic, consistent, masterful." (Okada 1991a, pp.15-16).

He was greatly celebrated in his own time, and he contributed to many of the illustrated manuscripts made for Emperor Akbar. He also produced a number of individual portraits and group scenes, often ink drawings or works in nim-qalam, and on several occasions copying, or at least strongly referencing, European prints, of which the present work is a superb example. The subject of this portrait is not obviously derived from a single European image, but it relates to at least two images of saints. The first is of St. Matthew the Evangelist, of which Kesu Das produced a version dated 1587-8 (Bodleian Library, Oxford, see Topsfield 2008, no.11, pp.30-31), which shows St. Matthew seated in a reclining pose, with his left hand holding the page of a book and his right hand writing in another book held by an angel. A cat, a ewer and a bowl are placed in the foreground. The second is the image of St.Jerome, in which the saint is shown seated in a room reading or writing (the image represents him translating the Vulgate Bible) with a lion at his feet (the lion's presence is based on the story that he removed a thorn from a lion's paw) and the lion is often depicted in a rather cuddly, tame, almost cat-like manner. An engraving of a work by Lucas Van Leyden of 1513 shows just such an image, even down to the way the saint is holding several pages of the book open with his fingers, as here in the Basawan drawing. In the present work Basawan, in typically confident and masterful style, has produced a portrait that is graphically brilliant and that expresses a dynamic and powerful originality and a complete understanding of both Mughal and European aspects.

The varied influences on Basawan's style gave rise to an interest in naturalism, observation and expression – both psychological and physical – that is often intense and direct. In the present case the figure of the man is acutely observed and candidly depicted. The taught, rotund belly is made larger and rounder by the position in which he is seated and the tightness of the waistband, so that the protrusion of the belly is pushed upwards towards his chest, providing a useful shelf upon which to rest his book. In contrast to this almost humorous passage, the face of the man carries a look of scholarly intensity and concentration, with wrinkled brow and thoughtful eyes. The physical presence of the figure is such that we feel we are not just looking at him, but sitting in the same room.

The key characteristics of Basawan's style are all present: graphic mastery, naturalism, psychological intensity, depiction of volume, love of flowing folds of drapery, originality of subject matter and composition. The portrait can be related to other works by Basawan, both in overall character and in individual compositional details. The closest in overall character is a nim-qalam portrait of a Seated Man even more corpulent and almost caricatural (Freer Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., see Okada 1991a, fig.12, p.13), which shows very similar treatment of the full belly, the tight waistband and the particular manner of drapery (notice the cuff of our figure's left sleeve and compare it to the flaring arms of the Seated Man's short-sleeved tunic; and our figure's hanging folds around his right ankle and shin and those around the Seated Man's right ankle). Even the puffy cushion against which both figures recline seems to be by the same hand. Certain facial characteristics of our figure can be discerned in a number of other works by Basawan, including Tamarusha and Shapur at the Island of Nigar in an illustrated copy of the Darabnameh (British Library, see op.cit. fig.4, p.5, Welch 1985, no.94) and A Mullah Rebukes a Dervish for Pride in an illustrated copy of the Baharistan (Bodleian Library, Oxford, op.cit. fig.5, p.7). While the various objects placed around the Learned Man in the present work are relatively standard elements mostly borrowed from European prints and employed by several Mughal artists, these particular examples have a strong similarity to the objects in a drawing by Basawan of A Young Woman and an Old Man (Musée Guimet, Paris, op.cit., fig.10, p.12). Closely comparable are the book, the footed bowl, the scribe's box, the ewer and the scroll (even down to the way the scroll lies flat on the box and then droops and curls over the edge).

For further discussion of Basawan see: Okada 1991a; Okada 1993; Beach 1981, pp.83, 100-102; Verma 1994, pp.83-94; Welch 1985, nos.87, 88, 94, 108, 110; Welch 1961.

In private notes Cary Welch had occasionally thought that this portrait might be the work of Daswanth, another of the great master's of Akbar's atelier, ranked third in Abu'l-Fazl's list of the best painters of the royal atelier, but in the published references, both those by Cary Welch and others (see above) the attribution is to Basawan. For a pertinent discussion of the differing styles of Basawan and Daswanth, see Beach 1981, pp.94-95.

A group of twenty-five leaves from the same album, including the present drawing, was sold in these rooms 15 June 1959, lot 118 (illustrated in the catalogue). They were acquired by Hagop Kevorkian of New York. Seven of these leaves, again including the present one, were sold again in these rooms, 1 December 1969, lot 126-132. Other folios are published as follows: Binney 1973, cat.no.49; Grube Kraus, no.239, pl.LIII.

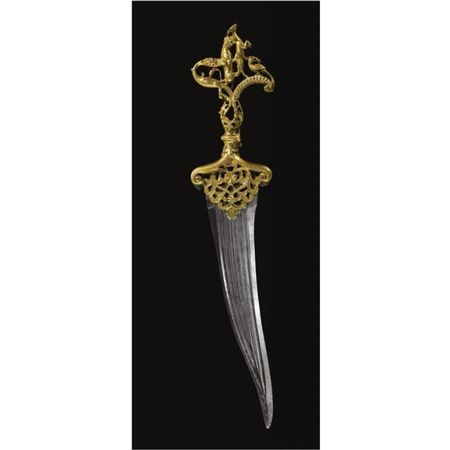

A magnificent Deccani ruby-set dagger with gilt-copper zoomorphic hilt, India, second half 16th century. Photo Sotheby's

with a curved steel blade, each face with six grooves converging below the tip, the hilt a narrow ringed grip of loosely baluster form with broad quillons in the form of down-turned scrolls, the forte composed of an openwork design of interlacing strapwork with chased beading emanating from a quatrefoil motif and stylised lotus and with scrolling foliate terminals, the hilt and pommel of cast openwork with chased detailing in a composition of fantastical and naturalistic beasts interweaving and attacking one another, the eyes and other elements set with rubies, plain cloth-covered wood scabbard and modern metal display mount; length: 39.6cm. (15 5/8 in.). Estimate 50,000—80,000 GBP. Lot Sold 802,850 GBP to an Anonymous

PROVENANCE: Howard Ricketts, London, 1974

NOTE: This is a most powerful and exuberant display of royal grandeur and visionary craftsmanship. The sculptural strength is skillfully balanced with exquisite detailing. An extraordinary range of artistic stratagem and motifs are unified into one object that encapsulates, in its dynamism and decorative range, the epitome of Deccani Sultanate art.

This form of dagger is known from a miniature of Sultan Ali Adil Shah I of Bijapur (r.1557-79), dating to c.1605, now in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington (Michell and Zebrowski 1999, p.232, fig.170). The only closely comparable dagger is in the David Collection, Copenhagen (ibid., p.231, fig.169). Another related piece but with damascened, or koftgari, decoration is also in the David Collection (Copenhagen 1982, p.142-3, no.100). The present example (formerly belonging to Howard Ricketts, London) is referred to by Zebrowski in his discussion of the group (ibid., p.232).

The beasts portrayed on the hilt are composed as follows: a parrot stands next to a tiger attacking a deer; the tiger is being bitten on its back by a serpentine dragon whose tail coils around the grip forming a ring around it; a demonic beast with openwork body and sectional, almost baroque, scroll tail is impaled by the dragon's tail. This combines imagery of hunting prevalent in Islamic courtly art with bestial imagery more familiar in an Indian context. This confluence parallels developments in contemporary painting, notably in Golconda, and all of these animals can be found in chased decoration of metalwork of this period (Zebrowski 1983, p.172, no.137, and Zebrowski 1997, p.353, no.580, respectively). It should also be remembered that this interaction reflected contemporary political and social events. Perhaps of greatest significance, during the reign of Ali Adil Shah I (1557-79), the Vijayanagara Empire, the one time ally of the Adil Shahis, was conquered by the confederacy of Bijapur, Bidar, Ahmadnagar and Golconda. In January 1565, they triumphed over their Hindu rival and seized land and booty with Bijapur reputedly benefitting more than most (Michell and Zebrowski 1999, p.13). Not surprisingly, many of these themes also occur in contemporary Goanese works, such as a gold sheath in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection, and the apparently baroque elements in the dagger hilt may be a response to the proximity of this European influence (Carvalho 2010, p.22-23, no.1).

This form of imagery has parallels in architectural decoration of royal patronage in Bijapur in the later 16th century. From this it can be argued that the dagger forms part of a conscious royal style for the reign of Ali Adil Shah I (1557-79) and his successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah II (1580-1627).

Two swords that relate to the dagger but carry simpler compositions give some clue to the subsequent history of this dagger. The swords, one now in the British Museum and the other in the Government Museum, Bikaner, both carry inscriptions mentioning 'Adoni', the Adil Shahi fortress. This fell to the invading Mughals in 1689 with the booty taken to Bikaner where many Deccani treasures remained for some time (Zebrowski 1997, p.102, no.107; and Welch 1985, p.48, no.17).

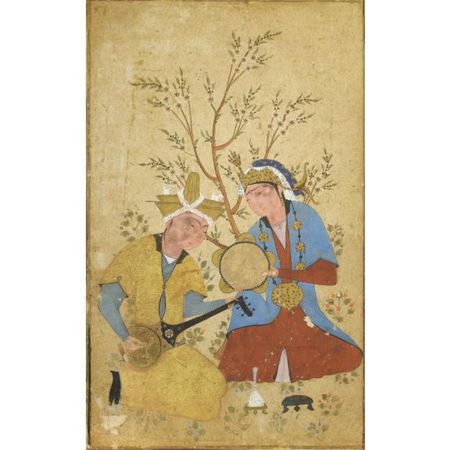

TWO MUSICIANS SEATED UNDER A FLOWERING TREE, MUGHAL, HUMAYUN PERIOD, CIRCA 1550.

Opaque watercolor with gold on paper, mounted with borders of red and buff paper; 20.2 by 12.2cm. (8 by 4 ¼in.). Estimate 70,000—100,000 GBP. Lot Sold 679,650 GBP to an Anonymous

EXHIBITED/ India, Art and Culture 1300-1900, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES/ Welch 1985, no.86, pp.146-147

NOTE/ This is an extremely rare and highly important example of Mughal painting from the reign of the Emperor Humayun (r.1530-1556). The stylistic influence of the painting is unmistakably that of the Bukhara school, reflecting the wider Central Asian and Persian influence on the early Mughal artistic output. The distinctive turban of the male figure (the Taj-i Izzat), which is specific to Humayun's close entourage, marks it out as Mughal. In the 1985 catalogue accompanying the exhibition India, Art and Culture 1300-1900, Cary Welch described the painting eloquently as follows:

"Were it not for the characteristic turban unique to Emperor Humayun and his court, this miniature might be ascribed to the Uzbek tradition, centered at Bukhara. Instead, the pleasingly moon-faced musicians, with their deftly drawn bird-beak noses, fingers suitably shaped like plectra, and gracefully arching brows, must be assigned to the little-known early phase of Mughal art. One senses non-Uzbek verve in the lyrically dancing trees keeping time with the music, in the zestful interaction of the lovers, and in the spritely duet of the tambourine and lute." (p.146)

Cary Welch rightly considered this painting to be an absolutely key work of early Mughal painting, and his hand-written notes on the backboard of the frame contain not only lyrical descriptions of the painting, but also striking art-historical insights, including a suggestion that the picture was painted for Mirza Kamran, Humayun's brother. Welch's notes are repoduced here verbatim:

"Musical Lovers: probably painted for Mirza Kamran mid 16th century." "Does this picture contain hints as to art of Babur's court? Does this represent a mode disliked by Akbar?"

"Mirza Kamran: bn 1508/9, mother Gulrukh Begam, Kabul entrusted to him at 18, Bada'uni says M K was brave, ambitious, liberal, good-natured, sound of religion, clear of faith"

"By Dust Mohammad Moghul ca. 1550"

"Kamran Mirza was Babur's second son, in 1530, Humayun conferred on him the government of Kabul, Qandahar, Ghazni and the Punjab. He was blinded at Kabul in 1553 because of his repeated offenses. Later he went to Mecca, where he died in 1556. He left three daughters and one son, Abul Qasim Mirza, who was imprisoned at Gwalior and eventually strangled by Akbar's order in 1565. An excellent poet and connoisseur of poetry. E & D IV, p.498"

"Strong Central Asian element of Uzbek tradition, a style in which artists reveal only moderate interest in most aspects of nature. Not easy, for instance, to identify species of birds and flowers, or to discover much about people, or their ages. Here we can say that the musical pair is young - but they could be anything from 16 or 17 to 25. This lack of concern for the facts of nature contrasts markedly with the character of the Moghul tradition, and it invites speculation as to what Moghul art might have been had Mirza K rather than Humayun been in the seat of power."

"Artist works in bold, sure, precise style markedly individual. Each area of colour separately pleasing as well as appealing in relation to the whole."

"Mood: musical, lyrical, he rapt in his music, she attentive to him."

"Figures large in scale - on white paper, bgd. [background]tinted yellowish cream; a flat world - not one that invites empathy. We "read" the picture rather than sense it. The forms indicate the subject but we do not hear the sound of music."

"Undulating dancing tree - lilting seemingly sways to music of lute and tambourine. Pleasingly moon-faced lovers with happy, bird-like features, his perfectly arched eyebrows, she bemused."

"Boldly composed, clean precision of forms - abstract patterns of blacks, blues, pinks, repeated circles, artfully placed black accents of hair, lute, collars and shoes. Large areas ... smaller, down to tiny 'grace notes' of pearls, jewels, edges of musical instruments - all contributing to vibrant whole."

"Colour: as in Bathhouse painting powdery blues, blue-greens, brownish red (rusty red). Flipper-like, tiny hands, large bulbous heads. Her face lighter-hued, nose orange, his darker, red brown."

"Line: with sharp point of brush, calligraphic, supple, "snappy", surprisingly graceful, musical."

"Influence of Safavid art in "Chinese" crown of princess and in overall elegance and courtly fripperies."

Other examples of early Mughal art from Humayun's reign are extremely rare, and those showing Bukhara influence even rarer. The most famous painting of Humayun's reign is the large painting known as Princes of the House of Timur, in the British Museum, datable to circa 1550-1555, with later additions (see Seyller 1994), and a small number of pages in the Jahangir Album in the Golestan Palace Library, Tehran and Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin are of the same period (see Tehran 2005, pp.420-421; Welch 1985, no.85, pp.144-5; Canby 1994, pp.20, 35). A drawing of the same period is in the Topkapi Saray Library, Istanbul (see Canby 1994, p.45). All of these are either signed by or attributable to Persian masters of the Safavid court of Shah Tahmasp who had come in to the employ of Humayun during his exile in Iran.

While Bukharan influence on early Mughal painting and the popularity of Bukharan works at the Mughal court is acknowledged (see Beach 1987, pp.37-49, 66-67, 69, 72, 76, 131), surviving early works that exhibit this influence are extremely rare. A key document of this early phase is an album known as the Fitzwilliam Album (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge and a few dispersed pages, see Beach 1987, figs.8, 16, 25-33), which contains an important group of paintings from the 1550s and 1560s, including several in Bukharan style and some in early Mughal style. It has been suggested that at least some of these may be Bukharan originals re-worked by Mughal artists a few years later (see Seyller 1994, pp.69-77, figs.24-26). A miniature in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, of a courting couple is painted in a similar Bukharan style to the present work, although, since the figures are devoid of the distinctive Humayun-style turban, assigning this miniature to the incipent Mughal school rather than the existing Bukharan one is open to debate (Coomaraswamy 1930, pl.XXIV; and Welch 1985, no.86, footnote 1, p.146). A group of Bukhara school miniatures in a copy of Jami's Yusuf va Zuleykha written for Humayun's brother Mirza Kamran have probably been inserted in to the text manuscript at a later date (see Schmitz 1992, II.15, p.114). The present painting is therefore an extremely rare work, which is of central importance to the history of early Mughal painting. For a full discussion of early Mughal painting see Beach 1987.

There are several interesting decorative details in the present painting. One is the small disc of micro-mosaic inlay in the centre of the lute. Another is the form of the brazier in the foreground, and a third is the style of heavy, ornate jewellery worn by the female musician.

PRINCE DANYAL RIDING A HORSE, ATTRIBUTABLE TO MUHAMMAD ALI, INDIA, DECCAN, AHMADNAGAR OR BIJAPUR, LATE 16TH CENTURY

Ink heightened with colour and gold on paper mounted on an album page with inner blue border and outer gold-flecked cream border. 21 by 15cm (8¼ by 5 7/8 in.); Estimate 20,000—30,000 GBP. Lot Sold 373,250 GBP to an Anonymous

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch 1994, fig.1, pp.407-428

NOTE: This exquisite drawing of a prince on horseback is an example of Deccani-Mughal work at its refined best; the quality of the rendering of the detail is breathtaking and under high magnification loses none of its crisp precision.

The inscriptions at the lower left identify the subject of the stylized portrait as Prince Danyal (1571-1605), the third son of Emperor Akbar. The drawing has been attributed by Cary Welch to the artist Muhammad Ali, who was active at the Mughal atelier of Emperor Jahangir, but who may have worked in the Deccan before moving to the Mughal court. Cary Welch and Robert Skelton have suggested that he worked in the Deccan, but Welch himself acknowledged that he was a "mysterious figure" (Welch 1985, p.231).

Aspects of the drawing relate closely to a painting of a princely hunter on horseback in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (formerly in the Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Collection, see Welch 1985, no.151, pp.229-231; Welch and Welch 1982, cat.65; Canby 1998, no.102, p.138, and cover illustration), especially the head and eye of the horse, the exquisitely rendered mane and tail, the delicate dappling of the horse's coat, the facial features of the prince and the gold hawker's drum. Other Deccani motifs present here are the attenuation of the figure, the manner in which the folds of clothing are gathered at the wrists and ankles, and the fluttering ends of the sash and jama behind the figure's right leg.

Beach describes Muhammad Ali as exhibiting "an extreme refinement of technique and sensibility..." (Beach 1978, p.144) and succinctly describes the debate concerning Muhammad Ali (and Farukh Beg, another Mughal artist showing Deccani tendencies): "Both show a general disinterest in Mughal trends towards naturalism; they use similar brilliant, strongly contrasting colors, ornamentally arranged floral forms, and flat backgrounds. Works by both men have strong affinities with paintings made at the Muslim courts in the Deccan, but whether this is due to similarity of temperament and interest, or actual contact, had not been firmly established." (ibid.) Canby notes that Muhammad Ali's distinctive palette and "hyperreal treatment of flowers and vegetation relate to Deccani painting of Bijapur", and that he "strikes a pictorial balance between the Persian, Deccani and Mughal styles, producing ideal men and women who inhabit a world of flowers and fragrant zephyrs." (Canby 1998, pp.138-9).

It is worth noting that, while this drawing is an idealized portrait of a young, probably teenage, princely figure, Prince Danyal himself was in the Deccan on military campaign in the last years of the 16th century with Akbar's general Abd al-Rahim Khanakhanan (who was a great bibliophile and patron, and maintained an active atelier while on campaign see lot 104 in this sale for more information). Prince Danyal was appointed viceroy of the Deccan in 1599, he conquered the city of Ahmadnagar in 1601 and died at Burhanpur in 1605.

Cary Welch's handwritten notes on the backboard of the frame are as follows:

"attributable to Muhammad Ali, Ahmadnagar, c.1585"

"By the same hand as: (1) Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah Riding through an Enchanted Landscape - Institute for the Peoples of Asia, Leningrad

(2) Prince Riding - Pr. Sadruddin Aga Khan, attributable to Muhammad Ali"

"Neeta Premchand says "Deccani Paper" "

"Slightly amused, contemplative horse, stressing inner characteristics - crisp, undulating outline - velvety softness, achieved by a fine "fur" , near(?) outlines - flying, fluttering, pulling out of forms - knotted tail etc- "

"Exaggeration of convexities and concavities - belly of horse, youth's supple figure"

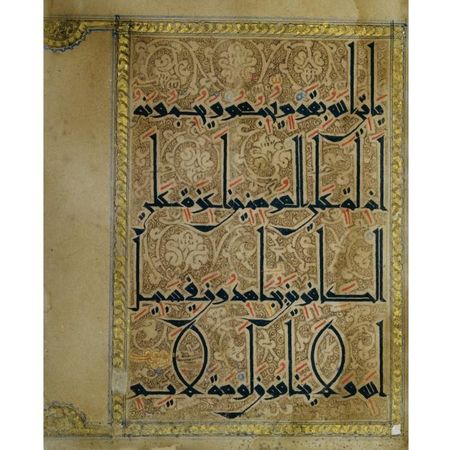

A LARGE AND FINELY ILLUMINATED QUR'AN FOLIO IN EASTERN KUFIC SCRIPT ON PAPER, PERSIA OR CENTRAL ASIA, CIRCA 1075-1125. Photo Sotheby's

Arabic manuscript folio, ink, colours and gold on paper; four lines per page written in fine Eastern Kufic script in black ink; letter-pointing (i'jam) in black, vocalization in red, blue and yellow, ruqa marked in gold cursive script at end of lower-most line of script; the entire background decorated with finely drawn floral and foliate scrolls in brown ink; verse division marked on verso with large gold radiating roundel containing the exact verse count using abjad letters (in this case 'nun-dal' = 54); the text area surrounded by a border band of lobed motifs in gold with half-palmettes extending into the margins from the upper and lower corners; folio 31.2 by 21.1cm. (12¼ by 8¼in.); text area 24.4 by 17cm.(9 5/8 by 6 ¾in.). Estimate 60,000—80,000 GBP. Lot Sold 325,250 GBP to an UK Private

PROVENANCE: This folio was in the collection of Stuart Cary Welch by 1961. He must originally have owned two folios: the present one bearing the text of Sura V, verses 54-55, and the adjacent folio, bearing Sura V, verses 55-57. Welch must have sold the second folio to his friend and co-collector Philip Hofer (1898-1984), for that leaf, exhibited in the exhibition Treasures of Islam in Geneva in 1985, sold in these rooms 15 October 1997, lot 10 and now in the David Collection, Copenhagen, bears an inscription in pencil in Philip Hofer's hand as follows: "12th C. Kufic. Bought of S C Welch 9/61.." (see Blair and Bloom 2006, p.91).

Fragments of only three sections of this Qur'an survive: juz' 6, juz' 14 and juz' 16. All those in Western collections are from suras IV and V in juz' 6. The folios in both the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the Cleveland Museum of Art were acquired in 1939, possibly from Kirkor Minassian, who supplied many of the institutional collections in the USA with rare books, manuscripts and calligraphy in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the Near Eastern manuscripts and cuneiform tablets in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. were acquired from Minassian in the 1930s. Since Cary Welch acquired a large proportion of the calligraphic works in his collection from Adrienne Minassian in the 1950s, it is likely that this folio and the others originally owned by Welch came from the same source. This would also fit with the date of 1961 when Hofer acquired his folio from Cary Welch.

EXHIBITED: Calligraphy in the Arts of the Muslim World, The Asia Society, New York; the Cincinnati Art Museum; the Seattle Art Museum; and the St. Louis Art Museum, 1979-80

Line and Space: Calligraphies from Medieval Islam, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, 1984

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Welch A. 1979, no.13, pp.64-5.

NOTE This folio is an example of one of the most striking and beautiful Qur'anic scripts. It originates from a Qur'an of majestic elegance and breathtaking graphic power, and the decoration of the background of the entire text area throughout the manuscript marks it out as one of the most luxuriously decorated Qur'ans of the medieval period. The original manuscript was produced in thirty volumes, each containing around seventy-five leaves, giving a total of approximately 2,250 leaves (Saint Laurent 1989). It must have been a truly majestic sight.

The calligraphic display is characterised by acute angularity and an almost ethereal attenuation. The tall, slim vertical letters contrast with the compact and tightly controlled sequence of letters that sit along the line, out of which the sub-linear tails of letters such as terminal nun extend, urging the eye of the reader along the line of script with rhythmic elegance. The tall, strong verticals of letters such as alif and lam also set up a beautiful contrast with the more subtle circular scrolling tendrils of the background decoration. And yet where the script produces a lam/ alif combination the scribe has curved both verticals in a concave manner to meet at the top, producing a perfect pointed oval which lies between the circular motion of the background scrolling and the vertical thrust of the tall letters. It is a calligraphic display that combines elegance, energy, originality and immensely skilful execution.

In relation to the technical aspects of the script, Anthony Welch has observed that the vertical letters are six to seven times the height of the others, and that where the word Allah occurs, the double lam in the middle of the word, nestling below the majestic initial alif, forms a shape resembling the single lozenge mark made by the impression of the reed pen on the paper, which is the basic building block of Islamic calligraphy. He suggests a spiritual aspect to the script in this context, where the foundation of the script (the lozenge dot) reflects the faith's true centre (Allah) (Welch 1979, p.64 and Geneva 1985, p.44).

Although other Qur'ans of the period show elegant calligraphic displays and fine background decoration within the text area (see Lings 2005, nos.12, 14, 15, 17, 21, 24) the majority have the background decoration only on selected pages, and in a more simple style of tightly scrolling whorls executed in one colour. In the case of the present Qur'an, every page appears to have been decorated with the more elaborate floral scrolls seen here, and it is to be noted that the colours used to draw the scrolling background alternated between the brown seen here, a darker, inky brown, and a pale blue (for example, a folio in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, formerly the Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Collection, see London 2007, no.5, p.34) The overall effect must have been truly breathtaking as the (no doubt princely) patron leafed through the complete manuscript.

The dating of the manuscript is based on two other Qur'ans which employ very similar scripts and decorative schemes, one of which was copied in 466/1073-74 by a scribe called Uthman ibn Husayn al-Warraq (Mashhad, Imam Reza Shrine Library, no.4316, see Lings 2005, no.14), and the other in 485/1092 (Istanbul, Topkapi Saray Library, R14, see Lings 2005, no.16). The question of the geographical origin of this Qur'an, and others in similar scripts, is an interesting one. While more cursive and less vertically stretched versions of so-called "Eastern Kufic" script (also referred to as broken Kufic, broken cursive, Persian Kufic, New Style and Qarmathian) were known and used in Abbasid Iraq and as far west as Sicily in the 10th and 11th century (the well-known Palermo Qur'an of 372/982-983 and the famous Mushaf al-Hadinah, or Nurse's Qur'an, made at Qairawan in 410/1019-20 are examples), it does appear that Eastern Persia had a particular taste for, and skill in executing, the types of graceful, attenuated and graphically extreme versions seen on this folio, especially those with an emphatic vertical thrust.

The production of ceramics featuring elegant varieties of Eastern Kufic script in brown or black on cream grounds (known as Samanid epigraphic pottery) was a speciality of Nishapur and Samarkand under the Samanid dynasty (247-393/861-1003) and represent some of the most elegant and arresting ceramics of the whole of Islamic cultural history (see, for example, London 1976, nos.279-281).

Other related examples of Eastern Kufic and ornamental Kufic script occur on Seljuk, Ghaznavid and Ghurid monuments in Eastern Iran and Afghanistan, and it is likely that the popularity of this type of script seen in the epigraphic tradition of this region was present in the Qur'anic calligraphy of the same period.

However, a more central geographic origin cannot entirely be ruled out, since there are examples of related scripts used in titles and headings of manuscripts produced in Iraq from the late 9th century onwards - the well-known Kitab al-Diryaq (Book of Antidotes), dated 1199 and produced probably in Northern Iraq (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, arabe 2964, see for example, Ettinghausen 1977, p.84), also employs a related script with a background floral scrolling decoration. Nevertheless, it has to be noted that most manuscripts from Iraq that employ this type of script do so predominantly in the context of titles and headings, rather than the main text, and by the mid-11th century in Iraq the calligraphic revolution set off by Ibn al-Bawwab's use of a small naskhi-style cursive script for his famous single-volume Qur'an of 391/1000-1001 (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ms,1431) had established the use of cursive scripts for the majority of Qur'an manuscripts in the central Islamic lands. Thus it remains likely that the Qur'an from which the present folio originates, and related types, was produced in Persia or Central Asia.

Another interesting aspect is the precise design of the background decoration of the text area, particularly the beautifully executed scrolling foliate motifs against which the script is set. A very similar motif is visible in one of the registers of the Minaret of Jam in Afghanistan, built during the second half of the 12th century (see Haussig 1992, p.85), perhaps strengthening the attribution of this Qur'an to an eastern Islamic origin. The scroll probably represents a stylized lotus scroll and, assuming that the date of this manuscript is the stated circa 1100 and the place of origin is indeed Eastern Persia or Central Asia, then it is interesting to note the spread westwards of this design, which appears in a very similar form in a Byzantine manuscript of Missals of the early 13th century (Moscow, GIM, Sin.604, see Dzurova 2002, no.106).

Other leaves from this dispersed Qur'an are in the following collections: