The Sinclair Collection of Early Chinese Bronze Vessels @ Bonhams

The Sinclair Collection of Early Chinese Bronze Vessels. Photo Bonhams

J. Goldstein emigrated in the 1920s from Poland to Canada, after his marriage to Ann, and the birth of his first child, a son. He settled in Toronto and had a thriving business trading in fur, designing, cutting and tailoring his own coats. His younger brother worked with their father in Poland in their very successful large fur store until, in 1939, he fled Poland, was imprisoned in Siberia, and ended up in Shanghai where he lived until the end of WWII. In Shanghai he was exposed to Chinese culture. Following WWII, members of the family, refugees at the time, were brought to Canada by Mr. Goldstein, including his younger brother. His brother's survival due to the goodness of the Chinese, the people of Shanghai, surely influenced his openness to Chinese culture, and could very well have been the root of his interest in Chinese art. Most likely Goldstein acquired the Fangyi, Gui and Zun, presently offered at Bonhams, in the 1960s. It seems the Fangyi was purchased on one of Goldstein's and his wife's many trips to New York. The Gui and Zun appeared on the market in Toronto, possibly from old 'missionary families' who had spent their early years, during the 1920's, 30's and 40's, in China serving the Anglican Church.

Remembering the economic stress of the 1920's, the Goldsteins invested in real estate as well as Chinese objects, partly as an investment, and due to his increasing interest in ancient Chinese art and culture. He believed China would one day open up diplomatically and economically. He passed away in June 1978 and his collection, including the three bronze ritual vessels, passed by descent through his wife to his granddaughter Mrs Sinclair. She was greatly influenced by her grandfather's collection and his interest in China. Mrs Sinclair travelled to Hong Kong and studied Mandarin, lived in Japan, and became a potter, specializing in regional Japanese pottery. She also lived in China teaching English. She spent considerable time in Singapore, the Philippines and Australia as well. The collection was later expanded with the purchase of other objects, encompassing archaic bronzes such as the Yu and Hu also offered in this auction.

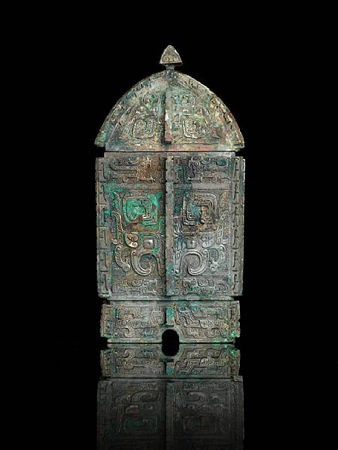

An important and rare archaic bronze wine vessel and cover, fangyi. Late Shang Dynasty, circa 1300-1050 BC. Photo Bonhams

The rectangular body finely cast in relief on each side with a central taotie mask composed of detached scroll and stylised mythical beast elements, divided by a notched flange along the vessel repeated at the corners, framed by borders of confronted stylised kui dragons, also around the foot, all reserved on a leiwen ground, the domed cover similarly cast on each side with a taotie mask reserved on leiwen ground and divided by a flange repeated at the corners, crowned with a knop finial, the interior of the vessel and the cover with an identical nine-character inscription, with heavy encrustations remaining particularly in the interior. 28cm high x 16.5cm wide x 14cm deep (11in high x 6½in wide x 5½in deep) (2). Sold for £1,196,000

Note: An identical inscription appears on a bronze jue vessel with lid in the Avery Brundage Collection, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, no.B60B104, which was first published by Luo Zhenyu, Sandai jijin wen cun, 1937, 18.20.4, and Zhou Fagao, et al, Sandai jijin wen cun shulu biao, Taipei, 1977 (see fig.1 above). As noted by Dr Wang Tao in his introduction to the Sinclair collection, the Avery Brundage jue and lid was formerly in the important collections of Ruan Yuan (1764-1849) and Pan Zuyin (1830-1890), which suggests that both the Avery Brundage jue and cover and the Sinclair Fangyi were originally part of the same set, and therefore would have been unearthed at the same time, prior to 1849.

Provenance: J. Goldstein, Toronto, prior to 1978, reputedly acquired from J.T. Tai, New York in the 1960s

Thence by descent to E.Sinclair

Rare bronze fangyi vessels are in several important museum collections; however, the Sinclair fangyi is extremely rare in its domed cover and clearly defined foot with a clear separation of the flanges between cover, body and foot. Only one other late Shang Dynasty fangyi of the same form with a domed cover, appears to have been published, see Zhongguo Qing Tong Qi Quan Jia, Vol.III, illustrated on the cover and on p.29. This one is similar but larger, from the tomb of FuHao, consort of King Wu Ding, excavated in 1976, Anyang, Henan Province, now in the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Compare a fangyi from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, no.1974.268.2, illustrated by R.W.Bagley in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Volume 1, Washington D.C., 1987, pl.78 (modelled with a triangular cover and continuous flanges from body to foot). For another Late Shang Dynasty fangyi in Harvard University, see Zhongguo qingtong qitu ji, Beijing, 2005, p.145 (of similar form but with a triangular cover). Compare a related bronze fangyi, Anyang Period, 12th-11th century BC, recently sold at Christie's New York, 16 September 2010, The Sze Yuan Tang Archaic Bronzes from the Hardy Collection, lot 822 (tapering form with triangular cover). See also a smaller related bronze fangyi, Shang Dynasty, 12th-11th century BC, sold at Christie's New York, 24 March 2004, lot 106 (similar form with a slightly different foot).

Observations on the Sinclair Collection of Early Chinese Bronze Vessels. By Dr. Wang Tao. Senior Lecturer, Chinese Archaeology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London

Fangyi. Among all bronze vessels produced in early China, the fangyi 方彝, a rectangular wine vessel, deserves special attention. First, it is extremely rare; it was made during a short period (Late Shang –Early Zhou, circa 1300-1000 BC), and only a handful of examples are known. Second, almost all fangyi are exquisitely decorated, indicating this was a special object associated with the ruling class of the society.

The bronze fangyi coming up in Bonhams London is a double surprise. It is largely unknown, having been hidden away in a Canadian collection for decades, and the quality of the piece is exceptional.

In terms of its form, the fangyi is a typical rectangular casket, supported by a hollow foot with an open arch. The casket has a roof-shaped cover that is again surmounted by a small roof-shaped knob. The decoration of both the vessel and the lid is very much in the late Shang style, with the taotie饕餮 mask on each side, and with the taotie on the cover facing upward. The taotie has square pupils, leaf-shaped ears, and large C-shaped horns. It is cast in high relief against the background of dense yunlei雲雷 spirals. On the foot there are two kui夔dragons on each side, facing in opposite directions. On the upper body of the vessel, above and below the taotie are confronted birds with hooked beaks and long-tails. There are heavy flanges - running along the corners and in the middle of each face of both vessel and lid - which are decorated with T-shaped grooves.

The round shape of most bronze vessels has been attributed to ceramic prototypes, where the earliest metalwork was under the supervision of the potter. The square or angular shape is clearly derived from other sources, probably a wooden box. The square vessels are much more difficult to make, and required higher technical ability and a greater investment of time and resources. This is probably why the fangyi type was rare and did not last for long.

Archaeology has shown that the fangyi first emerged in the early-middle Yinxu period, and disappeared soon after the early Western Zhou. The Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica (now in Taiwan) discovered three fangyi at Yinxu (two from Tomb 238 in Xiaotun, and one from Tomb 1022 in Xibeigang) in the 1930s. In 1976, the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences found three fangyi in the tomb of Fu Hao婦好, the consort of the King Wu Ding武丁. These are all Shang dynasty vessels. Western Zhou fangyi were discovered in Fufeng, Shaanxi province, also in the 1970s. Compared with the large, heavy fangyi of Western Zhou date, the majority of Shang pieces are smaller, usually between 20-30 cm in height, and decorated with the taotie motif and yunlei-spirals. Similar fangyi are found in the collections of the Shanghai Museum, the Palace Museum in Taipei, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Sackler-Freer Gallery in Washington DC, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Sackler Museum at the Harvard University, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst in Berlin, Museum Rietberg Zürich, and the Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum in Kobe, Japan. The Sinclair example is previously unpublished, and is therefore a new addition to our knowledge of this type.

The most valuable information about the object itself comes from the inscription cast on the inside of the cover and on the interior of the vessel. It consists of nine characters: Zi Shu (or Yan) Zai Zhi Zuo Wen Fu Yi Yi. The first character zi 子refers to the 'chief of the clan' in Shang oracle bone inscriptions, and is usually understood as 'prince'. The second character consists of five pictorial elements: four of them represent fire, and one depicts a human leg; there is no modern equivalent of this graph, but we can transcribe it, following the principles of the Chinese writing system, as (疋+炎), with a tentative pronunciation of shu 疋 or yan 炎; it is used as a proper name here. The third character is easily identified as zai在, meaning 'at'. The fourth character is pronounced as zhi (or di) 疐, referring to a place name. The fifth character is zuo作, meaning 'to make'. The sixth character is wen文, a graph of a man with patterns on his chest, meaning 'pattern' or 'culture', which is used here as an ancestral title in this case. The following two characters (put together as a single character) give the name of the ancestor fuyi 父乙 'Father Yi'. The final character is yi 彝, meaning 'sacrificial vessel'. Thus, the inscription can be translated as 'Prince Shu (or Yan) is at Zhi (or Di) to make a sacrificial vessel for the cultured ancestor Father Yi'. This is in the format of a dedication that is commonly found on Shang and Zhou ritual bronzes. But, the identification of the 'cultured ancestor Father Yi' is still uncertain: both the father of King Wu Ding, and the late Shang king Di Yi帝乙 could be addressed with the ancestral name Father Yi. There are two other inscriptions that mention 'Wen Fu Yi', or 'Cultured Father Yi', which date to the final phrase of the Shang and the early Western Zhou dynasty. Based on this evidence, I would date this fangyi to the late Yinxu period.

There is another bronze with an identical inscription. It is a lidded jue爵 goblet in the Avery Brundage Collection at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (see fig.1). The bronze jue was formerly in the collections of several famous Chinese connoisseurs such as Ruan Yuan 阮元(1764-1849)and Pan Zuyin 潘祖蔭(1830-1890), and was published by Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉(1866-1940)in his Sandai jijin wencun 三代吉金文存in 1937. To find a second bronze with the same inscription suggests that these bronzes were originally made as part of a set and had the same owner. If we compare the Brundage jue and the Sinclair fangyi, we notice similarities in the casting and style.

We may further comment on the name of the bronze itself. The character yi is written as a pictograph in early bronze inscriptions, where it depicts a bird tied up and placed on a altar. It is found on a number of early bronzes, both food and wine vessels. The early ritual text Zhouli 周禮records that yi-vessels, zun-vessels and lei-vessels were all used as wine containers in rituals, and that the yi was superior to the other types. The Zhouli also describes various forms and decorations of the yi (tiger, bird, chicken, and mythical beast). A close reading of the ancient texts and the objects offers us some interesting hints to understand the importance and significance of the bronze culture in early China.

An important and rare archaic bronze ritual offering vessel, fangzuo gui. Early Western Zhou Dynasty, circa 1050-900 BC. Photo Bonhams

The finely cast body of bombé form rising to the everted mouthrim, raised on a spreading foot cast integrally atop a square pedestal stand, the body cast in low relief on both sides with two taotie masks divided by a central notched flange, the neck with a narrower border enclosing a relief-cast bovine mask flanked by stylised dragons, the foot with a border of four pairs of silk worms divided by flanges, the body set with a pair of horned mythical-beast loop handles, cast on the sides with a fully formed bird, all atop the pedestal with cicadas at the corners above the sides cast with taotie masks flanked by birds, the interior with a 20-character inscription. 32cm wide x 29.2cm high (12 5/8in wide x 11½in high). Sold for £636,000

Provenance: J. Goldstein, prior to 1978, reputedly acquired from Frank Crane, The Hundred Antiques, Toronto

Thence by descent to E.Sinclair

The Sinclair gui on stand is extremely rare in its form and design. The design of the handles is particularly noteworthy with the rare casting of a complete bird on each handle below the horned head of the mythical beast. Typically, the bird design on the sides of the handles does not include the head which is presumably devoured by the beast; however, in the present gui, the bird is clearly defined from the beak, bulging eye in the form of a floral blossom above the wings cast with C scrolls, the long tail, legs and talons. This motif is further reinforced on the Sinclair gui by the taotie masks flanked on each side by a bird. A similar design can be seen on two vessels from the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C., a similar gui on stand, early Zhou Dynasty, late 11th-early 10th century BC, inv.no.38.20, illustrated by J.A.Pope, R.J.Gettens, J.Cahill and N.Barnard in The Freer Chinese Bronzes, Volume I Catalogue, Washington D.C., 1967, pl.63, p.350; and a bronze guang and cover, attributed to the early Zhou Dynasty, see J.A.Pope and T.Lawton, The Freer Gallery of Art, I, China, Washington D.C., pl.7.

Compare a similar gui on stand, but slightly smaller, dated to the reign of King Wu of the Western Zhou Dynasty, late 11th century BC, unearthed in 1976 at Linghexi Commune, Lintong County, Shaanxi Province, illustrated by Ma Chengyuan in Ancient Chinese Bronzes, Oxford, 1986, pl.35, p.110. See a smaller gui on stand with similar handles, from Harvard University Art Museums, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge, Mass., no.44.57.1, illustrated by J.Rawson in Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Volume 2 of Ancient Chinese Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Washington D.C., 1990, p.37, fig.35. See also a related bronze gui on pedestal stand, dated by inscription to the early Western Zhou Dynasty, sold at Sotheby's New York, 17 October 2001, lot 7. For another related example, see the one sold at Sotheby's London, 8 June 1993, lot 119.

Observations on the Sinclair Collection of Early Chinese Bronze Vessels. By Dr. Wang Tao. Senior Lecturer, Chinese Archaeology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London

Fangzuo Gui. Bronze vessels of the Shang period might already have had a pedestal made of wood or bronze. But, by the Western Zhou period, many gui-vessels were cast with a high square base, or with long legs in the forms of elephant head or bovine feet. The motivation may have come mainly from the desire to raise the height of the bronze vessels to make them look more imposing. The legged vessel may also have been functional: for warming up food during the ritual. Archaeology can now trace this particular form to the Zhouyuan 周原- the homeland of the Zhou people.

This bronze vessel has a number of comparable examples that date from the early-middle Western Zhou period, circa 1046-900 BC. The round bowl and the square base were cast at one pouring, and one can still see the marks underneath the vessel, which were left by the clay core. The form of this bronze vessel is imposing: the thickness of the wall and the moulding of the rim. It also has two massive handles that are surmounted with animal heads. The most dominant motif is still the taotie mask, which appears on the body as well as on each face of the square base. But, there are paired dragons on the neck of the bowl and cicadas on each of the corners of the base. These may indicate some changes in bronze style.

There is an inscription of 20 characters on the interior of the vessel. It reads: 'In the first month of the king's reign, Zhong Hui Fu made this food vessel, for his sons and grandsons to treasure forever.' Importantly, the same inscription also appears on two other bronze gui of later Western Zhou date, one of which is now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. However - whilst the dating of the vessel to early Western Zhou is not in doubt - the style of the writing, the execution of the inscription, which is relatively crude and knife-cut rather than cast, would suggest that the inscription may be a later addition, most likely added in the early 20th century to enhance its attractiveness and value. Therefore, the gui would have been unearthed in the early 20th century or earlier.

A rare archaic bronze ritual wine vessel, zun. Early Western Zhou Dynasty, circa 1050-900 BC. Photo Bonhams

The central register well cast with taotie masks composed of stylised dragons and C scrolls, divided by four notched flanges extending from the flared mouthrim to the foot, all between the neck with upright blades enclosing taotie masks composed of detached scrolls, and the foot with further taotie masks above the spreading footrim, all reserved on leiwen ground. 28cm high x 26.5cm wide (11in high x 10½in wide). Sold for £120,000

Provenance: J. Goldstein, Toronto, prior to 1978, reputedly acquired from Frank Crane, The Hundred Antiques, Toronto, in the 1960s

Thence by descent to E.Sinclair

Comparable bronze zun vessels of the Early Western Zhou Dynasty can be found in several important museum collections; see a slightly smaller example from the tomb of Yu Bo Ge, excavated at Zhuyuangou M7, Baoji, Shaanxi Province, illustrated by J.Rawson in Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Volume 2, Washington D.C., 1990, p.31, fig.22b. See also a slightly smaller zun vessel, circa 11th century BC, illustrated by Wang Tao in Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection, London 2009, pl.62. Compare a related archaic bronze zun, dated to the late Shang/early Western Zhou Dynasty, 12th-11th century BC, sold at Christie's London, 15 November 2000, lot 91.

Observations on the Sinclair Collection of Early Chinese Bronze Vessels. By Dr. Wang Tao. Senior Lecturer, Chinese Archaeology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London

Zun. Like the name yi, zun 尊is also a generic name for bronze wine vessels. It is written as a pictograph in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions, and depicts two hands holding a wine jar. The Zhouli 周禮lists zun together with yi as the main sacrificial vessels. This explains why the Song scholars began to use the name indiscriminately for a number of different vessels, including gu, zhi, hu, and lei. But, archaeologists use it only for a particular type of wine container. The zun category covers two distinguishable types: one has an angular shoulder and a trumpet-shaped mouth; the other is in the shape of a tall vase. The name zun is also used for wine vessels in the forms of animals.

The vase-shaped zun was popular during the Yinxu and Early Western Zhou period, and the Sinclair example belongs to this category. This bronze vessel shows a number of features of the 'transitional' style. It is tall, with a convex body and moulded foot; the body is further divided by four vertical heavy hooked flanges. The well defined taotie mask appears in relief on the middle and lower body, against the background of fine spirals. Similar examples are found in a number of museum collections.

Bonhams. Fine Chinese Art, 12 May 2011.. New Bond Street www.bonhams.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F13%2F119589%2F66288711_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F64%2F33%2F577050%2F65641082_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F80%2F577050%2F65456950_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F23%2F119589%2F65455871_p.jpg)