Million Pound Lots and Fierce Bidding Provide a Record Result at Bonhams Fine Chinese Art Sale

LONDON.- There was barely standing room and a tangible buzz at Bonhams Fine Chinese Art Sale in London today (12.5.11), which saw many items rocket way beyond their pre-sale estimates. The sale ended with a sold total of £16.9m with 95% sold by value.

This takes Bonhams Asian Art week total – including two Japanese Art sales (£1.6m and £1.7m) and an Asian Works of Art sale (£1.2m) at Knightsbridge to a massive £21,473,200. This result puts Bonhams in the lead on Asian sales in London at close of play today.

Colin Sheaf, Bonhams Asia Chairman and Head of Asian Art at Bonhams said: “This sale once again shows the power of the Chinese art market and the wish of buyers to obtain the best works of art. This sale set a new record total for Chinese Art at Bonhams and gives us the lead for Asian Art in London today. It is a fantastic feeling, especially after being on the rostrum selling the 556 lots from 10am to 7.30pm with one five-minute break!”

Top item in the sale was Lot 368, a rare pair of famille rose 'melon' teapots with iron-red Imperial Qianlong seal marks, moulded with five lobes in a naturalistic form, were estimated to sell for £20,000-30,000 but went on to achieve an astonishing £1,341,600.

These small delicate teapots had come from a Scottish private collection where for 50 years they had remained unsuspected as being of much value. Gordon Mcfarlan, Bonhams Director in Glasgow found them by chance. “I was asked by a client to collect a number of items from her home that she wished to sell. While I was there I spotted the teapots and told her I believed they might be important so she decided to consign them too. She had lived with the teapots for more than 50 years after her father collected them.”

Because expert opinion was divided over the provenance of the teapots Bonhams felt it could not guarantee the Imperial Qianlong history and so opted for a lower estimate allowing the market to decide their true value which it did decisively. The buyer from China will be taking them home.

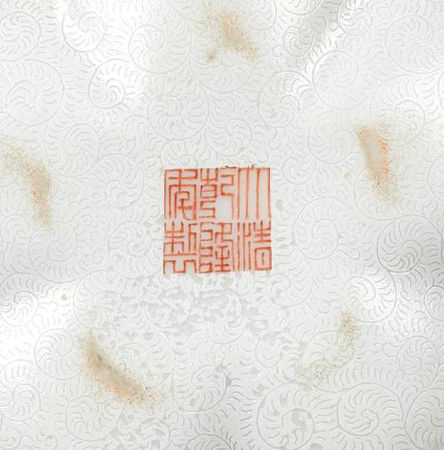

A rare pair of famille rose 'melon' teapots and covers. Iron-red Qianlong seal marks. Photo Bonhams

Each moulded with five lobes in a naturalistic form, the curving spout and handle enamelled en grisaille to simulate woodgrain, the handle turning into a shallow-relief spray coiling around each side of the body and applied with pink and white plum blossom sprays, the bodies and domed covers all under a white-enamel ground delicately incised with dense feathery scroll. 17cm (6 7/8in) wide (4). Sold for £1,341,600

Provenance: a Scottish private collection

Lot 81, a yellow jade sceptre (ruyi), linked to the court of the Qianlong emperor sold for £1,308,000, ten times its £120,000 estimate. According to the consigner’s family history, which is supported by records illustrating the progress of British troops in Beijing at the time, this ruyi was acquired by a military attaché posted to Beijing at the time of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. He was attached to the staff of Brigadier-General A. Gaselee, the commander of the British contingent assisting in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion on behalf of the Imperial Court, as one of the Eight Allied Powers.

Yellow jade was a favourite at the Qing court, and is believed to have been particularly admired by the Qianlong Emperor. The large number of Imperial vessels and decorative items worked from this sought-after colour that are held in the Qing court collections demonstrate its popularity.

A very fine yellow jade ruyi sceptre. Qianlong

Carved from a fine mostly even semi-opaque pale greenish-yellow stone with a few pale brown inclusions as a typical cloud-collar terminal, a small high-relief chilong curving around the upper edge, another crouching along the shaft and a third coiled in a loop at the pointed end of the shaft, the upper surface of the head with a wide shallow taotie mask, the upper side of the shaft with two crisp shallow relief cartouches of archaistic C-scrolls, the remainder of the body entirely plain, the surface attractively polished and lustrous, a double red silk thread tassel suspended from the end of the shaft. 37cm (14½in) long. Sold for £1,308,000

Provenance: According to family history, which is supported by family records illustrating the progress of British troops in Beijing at the time, this ruyi was acquired by a military attaché posted to Beijing at the time of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. He was attached to the staff of Brigadier-General A.Gaselee, the commander of the British contingent assisting in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion on behalf of the Imperial Court, as one of the Eight Allied Powers.

Yellow jade was a favourite at the Qing court, and is believed to have been particularly admired by the Qianlong Emperor. The number of Imperial vessels and decorative items worked from this sought-after colour in the Qing court collections suggest its popularity within the Qing court.

The popularity of yellow jade is well documented as early as the Ming Dynasty. In Sir Percival David's translation of the Ming Dynasty text Gegu Yaolun (Essentials of Chinese Connoisseurship) the different colours of jade are described as follows: White jade; the most valuable stones are of mutton-fat colour, those with the colour of ice or of rice porridge, of the colour of fat or of snowflakes, are next in quality. Yellow jade; stones with the colour of the chestnut kernel, known also as sweet yellow, are the most valuable.

The present ruyi is extremely similar to another in the Palace Museum, Beijing (fig.1), exhibited in Japan in 1982 and illustrated in S.Bijutsujan and A.Shinbunsha, Pekin kokyu hakubutsuinten, Tokyo, 1982, p.47, where it is dated Qianlong. This suggests that the present yellow jade ruyi is not only a product of Imperial patronage, but was also produced during the Qianlong period.

A yellow jade vase and cover in the Qing Court collection, inscribed with a four-character Qianlong mark, is worked with an almost identical taotie mask on either side of the body, see The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Jadeware III, Hong Kong, 1995, no.66.

A yellow jade brush washer, from the 'Pine and Bamboo Hall' collection, also dated to the Qianlong period and very similarly worked with a chilong dragon clambering over the rim is illustrated in Virtuous Treasures. Chinese Jades for the Scholar's Table, Hong Kong, 2008, Catalogue no.61. See also a yellow jade rhyton, again with chilong entwined around the body, illustrated in A Romance with Jade: From the De An Tang Collection, Hong Kong, 2004, Catalogue no.123.

Among other top lots were two 3,000 year old bronze ritual vessels that emerged from a little known Canadian collection created by a family who fled the Nazis and spent WWII in China, joining relatives in Canada after the war. Lot 249 sold for £1,200,000 and lot 250 for £636,000.

A set of ivory and zitan wood mounted erotic carvings sold for £804,000. This unique set of Chinese erotic ivory panels mounted in zitan wood screens possibly comes from the court of the Qianlong Emperor. The exquisite 18th-century ivory scenes show couples enjoying amorous embraces in a variety of leafy palace gardens. These superb panels of Oriental erotica are the latest discovery that will doubtless attract competition from Chinese bidders keen to buy back their heritage. Asaph Hyman, a senior specialist in Bonhams Chinese Department, says of the carvings: “The exquisite ivory panels mounted in zitan wood are a superb example of Qing dynasty ivory carving at its zenith. Given the rare quality and the use of this scarce zitan wood, an imperial court attribution is highly plausible.”

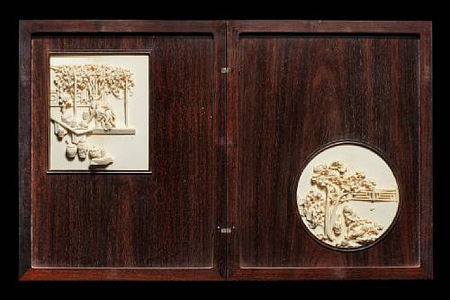

An important and rare eight-panel ivory zitan-mounted 'erotic' album, 18th century. Photo Bonhams

Each zitan double-panel formed as a book, performing a dual function of protecting the eight precious ivory carvings and revealing them discreetly when open, with the ivory panels consecutively numbered from one to eight, the eight erotic scenes superbly sculpted in minute detail with couples in amorous embraces, amidst terraces and luscious outdoor surroundings, the first ivory plaque carved with a five-character mark within a square reading Li Shou Zi Maobi. Each zitan panel 31.8cm x 24.6cm (12½in x 9¾in) (8). Sold for £804,000

Provenance: A & J Speelman, London

A German private collection

Exhibited and published: A & J Speelman, Chinese Works of Art, London, 2006, pp.66-67.

Ivory panel I

The dignitary, holding a fan in his right hand, stoops behind the pierced rockwork shaded by the large overlapping plantain leaves, gazing at the robed beauty, standing before a finely carved stand and tending to the incense burner and box, with the sun in the top left corner and the square seal, reading Li Shou Zi Maobi in the centre right, 10cm high x 10.2cm wide (3 15/16in high x 4in wide).

Ivory panel II

The dignitary and beauty, disrobed, engaged in an amorous embrace, in an idyllic setting below a gnarled pine tree with a bird perched at the top in a fenced garden, with a long pedestalled table and pierced garden seat amidst the rockwork, with a wine jar, kettle and cups set on a rock, the gentleman's robe draped over a garden seat at the foot of the tree, with two attendants standing in the foreground before a large pierced rock, a parcel of books and a half-covered box, 20cm high x 10.5 wide (7 7/8in high x 4 1/8in wide).

Ivory panel III

In a balustraded fenced garden scene, the couple are affectionately embraced, between a tall wutong tree and bushes amidst pierced rockwork, with the robes laid upon a garden seat carved with an openwork foliate scroll, with one of the beauty's shoes discarded in the background, 12.5cm x 12.2cm (4 7/8in x 4¾in) oval.

Ivory panel IV

The couple amorously embraced on a raised platform below dense and deeply carved grapevine draped from the wood canopy before a double-lozenge and double-ring carved fence, with a table in the foreground heavily laden with a gu vase issuing flowers, books, a dish with finger citron, a winepot, cups and a ruyi sceptre, with additional finely and realistically detailed vessels at the front, 13.8cm high x 11.8cm wide (5 7/16in high x 4 5/8in wide).

Ivory panel V

The beauty playing the flute, seated atop the dignitary on rockwork, below tall bamboo, with robes draped over the fenced garden, with an incense burner, tool vase and box on a stand, all below the crescent moon, 14.6cm high x 11.9cm wide (5¾in high x 4 11/16in wide).

Ivory panel VI

With the lady attendant playing the qin to the amorous couple, standing behind the willow and wutong trees amidst rockwork, their robes discarded on the rock, all before further trees and a lotus pond, 12.7cm high x 12cm wide (5in high x 4¾in wide).

Ivory panel VII

In a fenced garden, the attendant perched behind the rockwork below the plantain tree, is watching the embracing couple, engaged atop a rock ledge, with a robe draped over the fence and shoes placed on the ground, with a wutong tree in the foreground, 13.7cm high x 10.6cm wide (5 3/8in high x 4 3/16in wide) oval.

Ivory panel VIII

The masterful scene set atop a fenced terrace, with the dignitary and beauty further engaged, their robes draped over a fence and a pierced garden seat, with a table laden with flowers issuing from an archaistic gu vase, and a pair of peach, beside an additional garden seat, the foreground with an arched bridge over a lotus pond with swimming ducks, the terrace wall well delineated depicting the bricks, 17.9cm high x 11cm wide (7in high x 4 5/16in wide).

The exquisite, and in many cases, sculptural three-dimensional quality of the ivory carvings, coupled with the plaques being mounted in the specially-fitted lustrous precious zitan screens, all indicate an Imperial Court origin for the present lot and most certainly a special commission. Whilst paintings and works of art of erotic nature are known, none of the published examples would appear to be of comparison in its quality and its generous use, when compared to the size of the plaques, of the precious zitan wood. This too, would indicate that the present lot is not only extremely rare, but that an Imperial commission is highly plausible.

As noted by Tian Jiaqing in Classic Chinese Furniture of the Qing Dynasty, Hong Kong, 1995, p.37, 'Zitan ... has been highly valued in China from ancient times. In the Qing Dynasty, zitan and hongmu were the only woods chosen from which to make imperial furniture. Craftsmen only selected perfect zitan timbers ... by the mid-Qing period the supply of zitan was exhuasted ...'. By Qianlong's reign, special measures were taken by the Court to protect any existing stores of zitan which were kept in the warehouses of the Imperial Workshop. The Archives of the Imperial Workshop at Yangxin Hall (Yangxin dian zaoban chu ge zuocheng huoji qing dang) confirm that the use of zitan was scrupulously monitored and restricted to the Palace Workshops. Furthermore, The Qianlong Emperor gave instructions to ensure the most economical and responsible use of the palace's zitan supply to avoid any waste. Tian Jiaqing in 'Zitan and Zitan Furniture', Chinese Furniture. Selected Articles from Orientations 1984-1999, Hong Kong, 1999, p.194, mentions that the Archives of the Imperial Workshop at Yangxin Hall record that on one occasion Qianlong lost his temper because his wishes had been misunderstood and zitan rather than a less expensive material was used in a project.

The generous use of the prized zitan wood, as a mount for the ivory plaques, serves to underline the ivory carvings' importance as a superb work of art, worthy of being protected within precious mounts; it also underlines the probable Imperial provenance, and the discreet nature the zitan mounts provided when the books were closed.

Professor Craig Clunas notes in Chinese Ivories from the Shang to the Qing, London, 1984, pp.122-123 that according to Bushell, the Imperial ivory workshop is said to have been established in 1680 during the Kangxi period under the Zaobanchu. Bushell lists 27 workshops with ivory carving as no.14, and concludes: 'These ateliers, which lasted for a century or more, were closed one by one after the reign of Ch'ien Lung, and what remained of the buildings was burned down in 1869'. The list of workshops was taken from the 1818 edition of Da qing hui dian shi li (Collected Statutes with Precedents of the Great Qing). Though the exact number of workshops and date of establishment during the Kangxi period is disputed, amalgamation of workshops in 1758 resulted in no independent yazuo 'Ivory workshop'. However ivory carvers were members of the Ruyi Guan, and it may be assumed that ivory carving post 1758 was carried out by carvers attached to the Ruyi Guan.

The quality of the ivory carving, as exemplified in the attention to minute detail seen in the depiction of furniture, trees, terraces, fences, figures, and robes, is all comparable to that seen in the Qing Court Collection's Pleasure of the Court Ladies in 12 Months, dated to the middle Qing Dynasty, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Bamboo, Wood, Ivory and Rhinoceros Horn Carvings, 2002, pl.188. The depth of carving and naturalistic rendering of the trees is also comparable to that seen on an ivory brushpot, middle Qing Dynasty, from the Qing Court Collection, illustrated, ibid. pl.154.

Erotic art was known to the Imperial Court. See for example an erotic painting reported to have originated in the 'Palace at Peking', titled Subtle Pleasures of a Young Lord's Gynaeceum, attributed to Qiu Ying, early 16th century, from the Van Gulik collection, Paris, illustrated in M.Beurdeley, Chinese Erotic Art, Fribourg, 1969, p.198. Erotic art for domestic Chinese enjoyment was created in a variety of craft media, including soapstone, glass, and porcelain; see for example a blue and white rouleau vase, dated to the Transitional Period, sold at Nagel, Stuttgart, on 30 October 2009, lot 115.

Reflections of a Scholar: Looking at Erotica in Qing China

Anyone who enjoyed leafing through high-quality erotica in Qing China could not but regard such images with a degree of cultural awareness, likely of a visual or literary kind. An art lover or antiquarian, for instance, would have known about, even if he or she had not actually seen, paintings of the old master canon, like Night Revels of Han Xizai in the Palace Museum, Beijing, a probable twelfth-century painting attributed to Gu Hongzhong (937-975). Tradition has it that the painter Gu Hongzhong was sent by the Southern Tang emperor Li Houzhu (r. 961-975) to spy on Han Xizai (b. 902), a model courtier by day but also the subject of gossip about his dissipated lifestyle by night. The painting duly recorded, in a series of scenes, the unfolding of events over a single night of musical entertainment at Han Xizai's mansion. Later collector-connoisseurs through whose hands this famous painting passed - including the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736-95) - justified their ownership of it by emphasising its potency as a warning against the dangers of sexual abandon. Nevertheless, they had to view it first. It was also copied over the centuries, rather than being locked away.

The Night Revels exemplifies a particular pre-modern attitude toward erotic subjects in visual arts of China, but also demonstrates a standard in the visual presentation of this kind of subject matter in lavish if not palatial surroundings. Typically, such images are presented in a series of narrative episodes, either in a handscroll or a set, for example, of album leaves. The events depicted are like a progress of well-plotted stages or tableaux, which mirrors the manner in which one interacts with the object as a reader. To be seen at all, a handscroll must be moved back and forth by the viewer; the leaves of a concertina album need to be turned. This interaction happens in time and space, as at a musical performance or play. The object itself is not exactly passive in this process, but participates in it by giving up its secrets as a kind of reward for being closely examined.

The individual scenes in the ivory and zitan (purple sandalwood) erotic album work as a series of mini-narratives. The lavish furnishings, the rich patterning and texturing of the surfaces of things, from leaves to fabrics, and the deep relief carving though the ivory medium, combine to encourage and also reward intimate viewing. Where coitus is taking place in a particular scene, there is usually a clue as to how this state of affairs came to be: discarded robes are to be seen near or not so nearby. The opening and closing scenes also have specific functions in connection with the viewing process. The first scene shows a young man hiding under a banana tree in a garden, spying on a beautiful woman to the left who is unaware of his presence. He reappears later on. The boy's voyeurism speaks for the viewer's, as the viewer surreptitiously opens the erotic album (read from right to left), whether alone or in the company of a sexual partner, and peers through the variously shaped picture windows. Just as the opening scene provides a framework for the viewer's entree into the album, so the final scene rounds it off. The large mansion abutting the raised border around the ivory picture carved in high relief is not just an important signal about the elite social environment for the sexual escapades portrayed in the album, but also marks an end to its progress.

Just as such devices govern how the viewer opens and closes the album, so we may find naturalistic narrative features that determine the pace and enrich the experience of reading the album. The portrayal of the moon arcing across the night sky is an example. Not only is this an important poetic motif in its own right, with the power to conjure up a romantic mood, it also indicates temporal variations for the sexual encounters depicted. The moon is seen to move through its phases - now waxing new, then gibbous; now full, then waning. The balance of day and night scenes is also reflected in the balance of almost black zitan wood and off-white ivory, and both of these suggest the harmony of opposites, of the female and male elements seen in the traditional yin-yang symbol.

The scenes of erotic encounters between attractive young men and beautiful young women are in harmony with the natural variations of the sun and moon. The seasons also feature prominently. As is well known, erotic art as a genre is referred to in Japan as shunga, meaning 'spring painting', a term that derives from the Chinese. The word 'spring', chun in Chinese, has long been a euphemism for sex in East Asia. The vernal season is a time of rapid growth and tumescence in plant shoots and of sap rising. One of the scenes in the album depicts coitus taking place right beside a clump of bamboo stalks in spring, as shoots of remarkably thick girth burst up from the ground. In other leaves, flowers such as lotus blooms stand for the female sex. Lotus has long served in China as a figure of female beauty. Standing out of the water, it blooms in August at the peak of summer's heat, as shown in one leaf; by early autumn, as the temperature cools, the blooms fade and leaves of the plant curl and shrivel, as shown in another. These seasonal elements in the pictures, linking spring, high summer and then early autumn, provide, as it were, a natural guide for the naturists depicted within about how their combined sexual passion - and indeed the viewer's - might rise to a crescendo and then ebb away in accord with the seasons.

Although it is suggested that the ivory and zitan album may be an imperial production, it is nevertheless a distinctively Qing Chinese form of deluxe erotica. The women depicted all have bound feet, as Chinese women did from the Song to the end of the Qing dynasty (circa 12th-early 20th century). Women of the Manchu race which ruled Qing China did not bind their feet. Moreover, intermarriage between Chinese and Manchus was forbidden. This did not prevent the Manchu prince who would become the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723-36) from commissioning his now famous screens of Chinese beauties, Twelve Concubines of the Yongzheng Emperor. In each of these screens, amid finely appointed interiors, an imaginary Chinese court beauty awaits the arrival of her lover, the Manchu prince, with longing and ennui. In images such as these, desire and transgression seem to go hand in hand.

See the study by M.Sullivan, The Night Entertainments of Han Xizai: A Scroll by Gu Hongzhong, Berkeley, California, 2008.

For a new study on Qing decorative arts see J.Hay, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China, London, 2010.

See the exhibition catalogue by J.Rawson and E.S.Rawski, China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, London, 2005.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F52%2F577050%2F66521567_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F38%2F35%2F577050%2F66167687_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F06%2F577050%2F65483531_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F36%2F45%2F119589%2F65107496_p.jpg)