Sotheby's Islamic Sale Doubles Its Pre-Sale Low Estimate

16th century Ottoman gem-set box sells for £2.93million – more than four-times its pre-sale estimate of £500,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

LONDON.- Sotheby’s bi-annual Arts of the Islamic World Sale, which presented for sale works of art that span from the rise of Islam in the 7th century through to the 19th century, today achieved the record total of £15,447,450 ($23,772,081), well in excess of pre-sale expectations (est. £6.3-9.1 million). The well-attended auction, which achieved sell-through rates of 93.1% by value and 72.8% by lot, was headlined by the sale of a newly discovered early 16th century Ottoman Ivory and Turquoise-Inlaid Box set with rubies, which commanded the outstanding sum of £2.39million – more than four-times its pre-sale low estimate of £500,000.

Commenting on the exceptional results achieved today, Edward Gibbs, Senior Director and Head of Sotheby’s Middle East and India department, said: “Today’s sale presented collectors and connoisseurs in the field of Islamic Art with the opportunity to acquire some truly remarkable objects of quality and rarity, many of which were museum quality pieces. The record-breaking results achieved are testament to the desirability of these works of art sold today. We are delighted with the prices achieved for the newly discovered Ottoman box and Safavid Velvet, both of which achieved sums - far in excess of their pre-sale estimates – that reflect their standing as works of the highest aesthetic and historical value.”

Top-Selling Works of Art:

• The highest price achieved in today’s auction was for a newly discovered early 16th century Ottoman Ivory and Turquoise-Inlaid box set with rubies. Three bidders, two in the saleroom and one on the telephone, competed for the work of art, which finally sold to an anonymous buyer on the telephone for the remarkable sum of £2,393,250 – more than four-times its pre-sale low estimate (est. £500,000-700,000). This unique treasure, crafted by Persian goldsmiths working for the Ottoman court for a high-ranking courtly figure, is believed to have been made to contain scales to measure the weight of gemstones and was not known to exist until its recent rediscovery.

An Ottoman ivory and turquoise-inlaid box set with rubies, Turkey, early 16th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

of rectangular form, comprising two equally sized interlocking parts, the thin ivory walls bordered with wooden strips, enclosed within wide bands of niello and two shades of gold, intricately carved with a series of cartouches and roundels filled with scrolling split palmettes, carnations, lotus forms and saz leaves, the interior of the lid incorporating four corner spandrels and a central oval cartouche decorated ensuite with scrolling and interlacing gold flowers amid elegantly flowing palmettes and split-palmettes in niello, a single ruby set in the centre of the cartouche, the surface of the lid comprising broad bands of rectangular-cut turquoise stones set in gold channels with incised decoration, in a geometric pattern enclosed within a border, forming a six-pointed star at the centre, the interstices filled with alternating niello and gold scrolling flowers, each end with a panel enclosing two cartouches with inscriptions separated by a roundel, the central niello-ground stellar motif inlaid with a rigorous pattern of rumi arabesques and minute flowers in gold, the centre set with a single ruby in a gold petalled-setting - 17.3cm. length 8.8cm. width 3.2cm. height. Est. 500,000—700,000 GBP. Lot Sol 2,393,250 GBP

NOTE:inscriptions

nabvad mihaki hamcho tarazu be-jahan

ta sang-e sabokbar be-meqdar-e garan

yak kaffe-ye u buvad mah o digar mehr

oftadeh qeran-e mehr o mah dar mizan

'There is no touchstone (?) like these scales in the world,

To measure stones light and yet precious.

One tray is like the moon, the other the sun,

The conjunction of the sun and moon has fallen in its balance'.

This superlative object highlights the exceptionally refined masterpieces produced by Persian goldsmiths working for the Ottoman court at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Its sumptuous ornamentation is unmatched in elegance and skill, rendering it an incomparable item of the highest aesthetic and historical value.

Centred on a ruby jewelled-rosette, its ivory filets and mosaic-sliced turquoise or firuzekari finely frame a series of symmetrical panels containing intricately carved and gold-inlaid vegetal patterns in what can be called the 'international Timurid style'. Though the floral decoration is highly reminiscent of Ottoman fashion, the meticulous nielloed gold work recalls Safavid traditions and its superb quality is only matched by a handful of items now at the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul. They provide insight to the astonishing talent of Safavid craftsmen during the first half of the sixteenth century, of which the current piece is an example of the utmost excellence and rarity.

The extravagant luxury of Persian work comprising precious metals and stones is recorded in early sixteenth-century accounts of Portuguese ambassadors to Shah Ismail's court. During his stay at the Shah's encampment near Tabriz, Portuguese ambassador Tenreiro described 'bottles of gold and silver with turquoises and rubies inchased upon them' (R.B. Smith, The First Age of the Portuguese Embassies, Navigations and Peregrinations in Persia 1507-1524, Besthesda MD 1970, p.72). These objects were meant for the exclusive use of the Shah and the most exclusive governing elite. Tenreiro himself notes the difference between the bejewelled examples and those just of silver, which were intended for less prominent members of the court (James Allan, 'Early Safavid Metalwork' in J. Thompson and S.R. Canby (eds.), Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran 1501-1576, p.203).

A decisive victory at the battle of Chaldiran on 23 August 1514 marked Selim I's successful campaign against Shah Ismail and led to the subsequent occupation of Tabriz, during which an important number of the Shah's treasures were captured as booty and taken back to Istanbul. Of these items, it is worth drawing attention to a group of plaques from a belt bearing the titles and name of Shah Ismail I as well as an armband signed by the craftsman Nur Allah, now in the Topkapi Saray Museum (see ibid., no.8.1 and 8.3). Dated 913 AH/1507-8 AD, their intricate and varied arabesque designs on gold are the work of a true virtuoso and echo the present box's layered split-palmette scrolls in carved and inlaid gold. The parallels are even more evident in the most ornate buckle, which contains comparable blossoming rosettes set with rubies and turquoise gems.

Attention can be also drawn to a flask and cup of gold-inlaid zinc, which J. Michael Rogers suggests were probably captured during Selim I's occupation of Tabriz (see J. M. Rogers in Jay A. Levenson (ed.), Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration, New Haven and London 1991, pp.205-6 nos.98-99). The openwork gold plaques on these zinc vessels also reflect the distinct 'international Timurid style' of flattened palmettes that is displayed on the exterior panels of the current lot. They too are similarly heightened by nielloed grounds and encrusted with precious stones.

Though treasure taken by Selim during the sack of Tabriz no doubt included the finest of objects, amongst the most precious assets sent to Istanbul we must consider the skilled artisans who were captured and taken to work in the Sultan's workshops. Persian goldsmiths or 'Acem had been active in Istanbul as early as 1480 (ibid, p.205), but it is reasonable to infer that the influx after 1514 was crucial in establishing their prominence in the Ottoman capital. This is made unambiguous by the 1526 payroll document of the Topkapi Palace, which notes that both the damasceners' and goldsmiths' guilds were headed by craftsmen from Tabriz (Allan, op.cit., pp.213-4).

Perhaps the most comparable example is a pen case with inkwell from circa 1500 also in the Topkapi Saray Musuem (see Rogers, op.cit., p.204 no.97). Its turquoise fittings, set rubies, and lateral inscription cartouches closely resemble those on the present box. Though Allan suggests that the object belonged to the Shah himself and was part of Selim's booty, Rogers attributes this piece to an 'Acem, placing importance on the Ottoman floral ornamentation on the barrel caps. These concentric intertwining arabesques find stylistic parallels in a selection of Ottoman objects of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. Principal amongst these surviving objects are bookbindings and manuscript illumination. More specifically, the multi-pointed star motif filled with rumi arabesques, which is the central feature of this box, can be traced to imperial bookbindings as early as the 1460s/70s (see, for instance, J. Raby and Z. Tanindi, Turkish bookbinding in the Fifteenth Century. The Foundation of an Ottoman Court Style, London 1993, p.150, no.20) and continues in multiple and increasingly complex variants until the mid-sixteenth century (see the carved ivory mirror made for Sultan Suleyman in 1543/44 (inv. No.2/2893), published in A. Atil, The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, Washington, 1987, p.139, no.73).

Furthermore, an important analogous box specifically notable for its sanctity is a reliquary for a hair of the Prophet Muhammad from the mid-sixteenth century now at the Topkapi Saray Museum (see D. J. Roxburgh (ed.), Turks: A Journey of A Thousand Years, London, 2005, p.328, no.301). Strong resemblance is visible in the turquoise mosaic, ruby gems and split-palmette patterns, but particularly in the ivory filets, carefully fitted along the object's edges.

Regarding the box's practical function, the lateral inscription cartouches provide considerable insight. It can be inferred from the first two verses, 'There is no touchstone (?) like these scales in the world / To measure stones light and yet precious', that they contained scales precise enough to measure the weight of gemstones. The ivory interior, decorated with a central jewelled medallion and four corner spandrels also in gold and niello, shows vestiges of either an internal fitting or the original contents that are so gracefully described by the poetic calligraphy on the exterior.

The amalgamation of Safavid and Ottoman traditions in the present piece is evident from the strong correlations with the various objects previously mentioned. As a link between the traditions of Tabriz and Istanbul, it thus embodies a cultural merging of noteworthy significance to the stylistic evolution of Ottoman courtly art at a seminal phase in its development.

• Continuing Sotheby’s established track record of achieving strong auction prices for Safavid velvets, today’s sale witnessed a 16th or 17th century Safavid brocaded silk and metal-thread textile panel from Persia sell for the exceptional sum of £1,609,250 - more than five times its pre-sale low estimate (est. £300,000- 500,000) - establishing the second-highest price of the auction. The velvet textiles of Safavid Persia have long been revered for their sophistication of design, their lavish use of materials (silk, often wrapped with silver and gilt foil strips) and extremely complex structure and the previously unpublished velvet sold today was believed to be from the same textile as fragments that are now in the Bargello Museum, Florence, the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon and the M.H. de Young Museum, San Francisco.

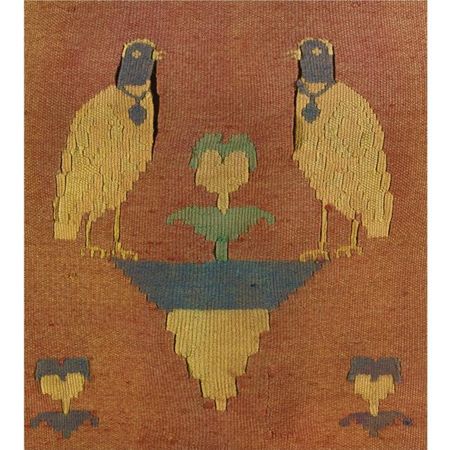

A Fine Safavid voided silk velvet brocade, Persia, 17th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

of rectangular form, the voided green and red velvet on canary yellow woven ground, assymetrical design with lobed medallions enclosing pomegranate design surrounded by a wreath of flowers, connected by varied trellis incorporating pairs of confronting peacocks and addorsed birds of paradise, traces of metal-strips to ground weave - 83.5 by 100cm. with border 57.3 by 71cm. without border. Est. 300,000—500,000 GBP. Lot Sold 1,609,250 GBP

PROVENANCE: Collection M. Besselièvre, sold Hotel Drouot, 16-17 February 1912, lot 39 or 42.

EXHIBITED: This previously unpublished velvet appears to be from the same textile as fragments that are now in the the Bargello Museum, Florence, the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon and the M.H. de Young Museum, San Francisco. All three of these examples have been published as listed below;

Bargello Museum, Florence, Italy:

Carolo Maria Suriano and Stefano Carboni, Islamic Silk: Design and Content, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Firenze, 1999, cat. No. 41, pp. 122-125.

G. Curatola and M. Spallanzani, Mattonelle Islamiche, Esemplari d'Epoca e loro fortuna nella Manifattura Cantagalli, Florence, 1985, pl. 165, pp. 367-368.

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal:

Maria Teresa Gomes Ferreira et al., Tecidos da Coleccao Calouste Gulbenkian, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, 1978, no. 30.

Richard Ettinghausen et al, Persian Art: Calouste Gulbenkian Collection, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, 1985, no. 23.

Ernst Flemming, An Encyclopaedia of Textiles, New York: E. Weyhe, 1927, p. 296.

M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, California:

Adèle Coulin Weibel, 2000 Years of Silk Weaving, New York: E. Weyhe, 1944, no. 251, pl. 60; catalogue to an exhibition sponsored by the Los Angeles County Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

NOTE: The presence of a metal "Douane" tag on the lot offered here suggests that it too may have been in the collection of M. Besselièvre and sold at the Hotel Drouot in Paris in 1912 along with the Gulbenkian velvet cited above. The lots in the Besselièvre catalogue have very brief descriptions, with only a few being illustrated and there are no measurements listed. While we cannot definitively state it, it is possible that the velvet offered here was either lot 39 or lot 42 in the Besselièvre sale, described respectively as "Fragment de velours polychrome ciselé, sur fond lamé d'argent doré, à dessin de branches fleuries, sur lesquelles sont perchés des oiseaux. Ancien travail persan." and "Carré de velours, à ramages de fleurs et d'oiseaux, en jaune et vert, sur fond rouge. Ancien travail persan."

The velvet textiles of Safavid Persia have long been revered for their sophistication of design, their lavish use of materials (silk, often wrapped with silver and gilt foil strips) and extremely complex structure. Here the two-plane lattice design is punctuated by pairs of affronting and addorsed exotic birds. Related ovigal lattice design velvets include a fragment in the Textile Museum, Washington, D.C., see Carol Bier, Woven from the Soul, Spun from the Heart, Washington, D.C., 1978, pl. 9, p. 153, where the author relates a 1615 anecdote demonstrating the high value placed on Safavid velvets: "Sir Thomas Roe committed a faux pas at the Mughal court by presenting a coach upholstered with Chinese velvet as a gift to Emperor Jahangir. Displeased with the quality of the velvet, Jahangir had it replaced by 'gould Persian veluett,'" see Roe, Sir Thomas, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe, reprint 2 vols., Nendeln, Liecht.: Krause Reprint United, 1967, pp. 118, 322-323.

• Part II of ‘The Tipu Sultan Collection’ presented for sale six outstanding items including weaponry and other rarities captured after the British stormed the autonomous Muslim Ruler, Tipu Sultan's palace at Seringapatam in May 1799. The collection carried a combined estimate of £223,000-291,000 and saw all six works of art achieve a combined total of £1,079,750 – almost four times the combined pre-sale high estimate. (The first part was of ‘The Tipu Sultan Collection’, which was offered at Sotheby’s London in 2005, brought £1,239,240/$2,267,437.)

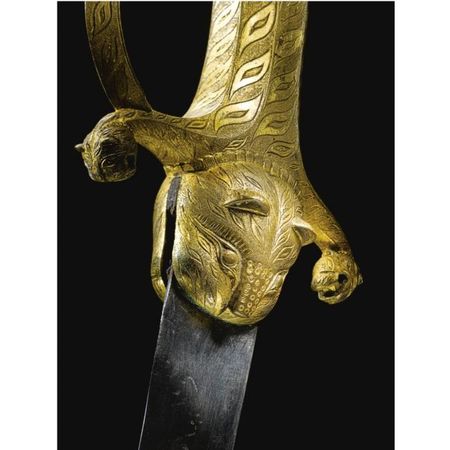

• The top-selling object of the group was a very rare sword and scabbard with Tiger-Form Hilt, from the Palace Armoury of Tipu Sultan, India, circa 1782-99 (formerly in the collection of Viscount Strathallan), which sold for £505,250, more than ten times its pre-sale low estimate (est. £50,000-70,000).

A Very Rare Sword with Tiger-Form Hilt, from the Palace Armoury of Tipu Sultan, India, circa 1782-99, with 19th century silver-mounted scabbard. Photo: Sotheby's.

the long slender single-edged tapered finely watered-steel blade, the fine bubri engraved bronze hilt in the form of a tiger head at the forte and pommel with smaller tiger-heads as quillons, the leather-covered wooden scabbard with ensuite silver chape, lock and suspension mounts - 93cm. Est. 50,000—70,000 GBP. Lot Sold 505,250 GBP

PROVENANCE Formerly in the possession of Viscount Strathallan.

NOTE: inscriptions

The only word barely visible is dhu 'l-faqar, the name of Imam 'Ali's sword.

Tipu Sultan's swords echo the aesthetic sense of his complex personality, they are masterpieces of craftsmanship. A very small number of sword hilts, such as the present example, share a pronounced tiger theme closely linked with the personal ownership of Tipu Sultan himself. One was found on Tipu's body at his death in Seringapatam, now in the Royal Collection at Windsor (ref. RCIN 67216). Another example can be found in the collection of the second Lord Clive, preserved at Powis Castle.

• An Extremely Rare Indian Bronze Cannon cast by Ahmad Pali, for Tipu Sultan, dated Mawludi year 1219, sold for £313,250 (est.120,000-150,000) achieving the second highest price of the group.

An Extremely Rare Indian Bronze Cannon cast by Ahmad Pali at the royal foundry at Seringapatam, for Tipu Sultan, dated Mawludi year 1219 (1790-1 AD). Photo: Sotheby's.

the tapered characteristic form with convex mouldings and raised rings dividing the advancing segments, the muzzle decorated with leaves and cast with a series of raised cartouches comprising inscriptions, the chase with bubri-shaped cartouches and founder's name and mawludi date, the talismanic square divided by bubri, the muzzle, trunnion ends and cascable button cast in the form of tiger heads - 254cm. Est. 120,000—150,000 GBP. Lot Sold 313,250 GBP

NOTE: inscriptions

Talismanic device: H/Y/D/R 'Haydar'

19th Century British inscriptions: ANO 10 2 PR / 9-0-19 (twice) / 2 PR

'Triumphant Lion of God! From the computation of the letters the year of accession of Sarkar-e-Haydari will be found, the year zebarjad, the year 9121 of [the Prophet] Muhammad'.

'The craftsman Ahmad Pali'.

'Unloaded weight of the cannon fourty-four pounds one grain, weight of shot ninety-six nuts'.

'Manufactured in the capital Patan'.

Tipu Sultan and his father, Haidar Ali, dominated South India for over thirty years between 1767 and 1799. Tipu Sultan was a legend in his own lifetime. He foresaw a strong Navy and Army that would have strategic value to match his fighting opposition. He had a great military mind, designing his own army and weaponry, but still understood that his strength lay with his subjects.

Tipu founded his capital at Seringapatam where he ruled his kingdom of Mysore. During his lifetime he established two foundries for brass cannon, arsenal and powder magazines, one at Seringapatam and the other at Bangalore. At the fall of Seringapatam, 927 cannon were captured of which over half were cast at his foundries. The present example carries the Haidar talismanic square which indicates that it was cast at the Royal foundry.

The more popular image of Tipu was as a tryant, monster, bigot, inhumane and dedicated towards a holy war against his enemies. However, he is also recognised across the sub-continent as a nationalist hero who struggled for independence but stood up to the British, dying defending the gates of his palace against the imperial oppressor.

Tipu's personal insignia was the tiger. Through this, all of his possessions, including the garments of his courtiers and soldiers were adorned with tiger stripes or bubris. The classic bubri is an S-shaped form, wide at the middle, with a hollow centre and re-curving ends of equal size. The motif was adopted around 1780 and was continued until his death in 1799. Tipu's name in Canarese means tiger and he was given this name by his father (whose name can also mean tiger or lion). This ornamentation featured on every item at his court from the infantry tiger jackets, to objects themselves made in tiger form.

As well as this, a further motif which was often found on Tipu's armoury, also derived from his beloved tigers. A written symbol in Arabic 'Asadullah al-Ghalib' meaning 'The Victorious Lion of God' or 'The Lion of God is the Conqueror', obviously in reference to himself, can be found on the present cannon. The characters in this cipher can be carefully arranged and then mirrored to resemble the face of a tiger.

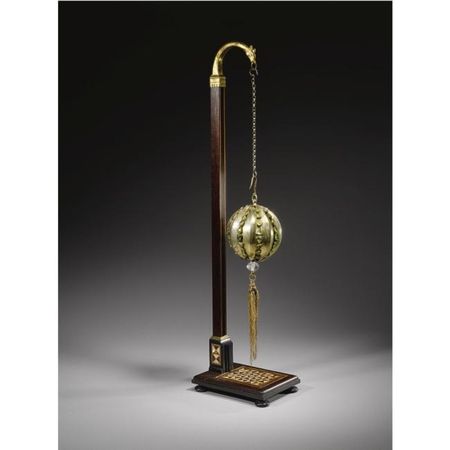

• A magnificent and exceptionally rare 17th century Ottoman silver-gilt cantaloupe melon-form hanging ornament, decorated with vivid Peridot gems, which was intended to hang above the throne of a royal figure also highlighted today’s auction. This remarkable artistic treasure of the Ottoman Empire sold for £601,250, more than triple its pre-sale high estimate (est. £150,000-200,000).

An Ottoman silver-gilt hanging throne-ornament set with peridots, turkey, 17th/18th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

the eight-ribbed cantelope melon-form ornament set with peridots, mostly cabochon, in the contours, at the base a large rock crystal bead emanating a thread tassel, original chain suspended from a later silver-gilt engraved horsehead stand and wooden and mother-of-pearl-inlaid base - 135 cm. overall from suspension hook to lower tip of tassel 15 cm. height 13.5 cm. diam. Est. 150,000—200,000 GBP. Lot Sold 601,250 GBP

NOTE: The best known Ottoman goldsmith's work decorated with peridots is the Bayram Tahtı, on which the Sultan was accustomed to receive the highest dignitaries of the Empire on the great feasts of the Muslim year, which was originally encrusted with 954 of the stones on gold sheet covering a walnut armature. Paintings of sultans enthroned on it show that it originally had a baldachin that could be removed, and by the 18th century the throne was set up in the portico of the Babüssaadet, on the axis of the Second Courtyard of the Topkapı Palace with the pendant hanging on a chain from the roof.

The Bayram Tahtı is often associated with Murad III (r.1574-1595), who is reported to have inaugurated it in 993 AH/1585 AD, and was presented by his vizier, Ibrahim Pasha on the occasion of his marriage to the Sultan's daughter, Ayse Sultan. But, even making allowance for exaggeration and inaccuracy on the part of the writers who have described it, the details do not correspond at all closely with the actual throne. The earliest register in which a Bayram Tahtı is listed is dated 1091 AH/1680 AD (Topkapı Saray Archives D.12), and, to judge from the portraits of the Sultans, most of them without a pendant, it was mostly used in the 18th and 19th centuries. Peridots were mined in quantity in Egypt (on the island of Zabarjad in the Red Sea) throughout the Ottoman period and the Treasury of the Topkapı Palace still contains large numbers of polished but unset stones.

The historians relate that from the earliest centuries of Islam it was the custom of rulers to send valuable ornaments to be hung at the Ka'bah in Mecca and in the Tomb of the Prophet at Medina. Such pendants very probably included the spectacular jewellery with large emeralds now in the Treasury of the Topkapı Palace. The earliest depictions of hanging ornaments in shrines are in Matrakçı Nasuh's account of the principal stages of Süleyman the Magnificent's Persian campaign of 1534-1535 Mecmu'a-yi Menazil (Istanbul University Library T 5964), folios 64b Mashhad 'Ali/ Najaf and 109a showing that of Seyyid Battal Gazi. The manuscript was dated 944/1537-8 in the colophon, which has now been lost.

The earliest representations appear to be from the reign of Murad III(1574-95), when, in the Hünername (H.1524) of 996/1587-88, which was written for him, the Divan, the Council of State, is shown in session in the Kubbe Altı with a globe hanging at the centre of the chamber. There is also a miniature showing Selim II, evidently flown with wine, from his private chamber above it using the globe for impromptu archery practice, which suggests that the Sultan was free to commit lese majesté if he so desired. A manuscript in Vienna of c.1590 also depicts Murad III enthroned in the Arz Odası receiving an Austrian embassy, with two eggs hanging from the roof.

Notwithstanding, the pendants continued to be very various in their forms, some of them almost suggesting turban ornaments, and just as the later Sultans all seem to have had their own, so each may have had his particular pendant. None of the earlier ones appear to be eggs. Ostrich-eggs, however, showing elaborately and expensively decorated, and 'Damascus eggs', shiny glass balls, are listed in the building accounts for Süleymaniye (inaugurated 1557). They were also particularly used to decorate tombs. Stefan Gerlach, who was in Istanbul in 1574, a matter of months after the death of Selim II visited his tomb and describes round mirrors (shiny glass balls?) on silken strings with fine silken tassels hanging from them. In the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul is a silver egg (TIEM 210) presented by 'Abdülhamid II to the shrine of the Sufi saint, Emir Buhari, at Bursa. On the other hand, they were copied in popular art: in the Surname-yi Humayun of Intizami (TKS Library H. 1344), an account of the festivities attending the circumcision of the sons of Murad III in 1582, the procession included a series of craftsmen bearing tiered constructions (nahil or nakıl) surmounted by stars and candles, which to the onlookers resembled ingeniously contrived artificial trees, with all sorts of painted glass and paper globes, flowers and tasselled pendants. They were not an invention of the period of Murad III, however, but were brought out on the occasion of the marriage of Süleyman the Magnificent's favourite and Grand Vizier, Ibrahim Pasha in 1524.

By the 19th century when the egg-shaped pendant seems to have become the standard, ovoids were used by other members of the royal family besides the sultan, notably by the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan). The evidence thus seems to show that a custom originally associated with shrines was taken over by the Ottoman Sultans as part of their regalia, which aptly symbolised their claims to spiritual as well as secular authority.

Firuze Preyger, 'Bayram tahtı', Türk Etnografiya Dergisi xiii (1973), pp. 71-8; H.F. Brown, 'The marriage of Ibrahim Pasha', in H.F. Brown ed., Studies in Venetian history ii (London 1907), pp. 134-45; I.H. Uzunçarılı, Nahil ve nakıl olayları', Belleten xl (1976 ), pp. 55-65.

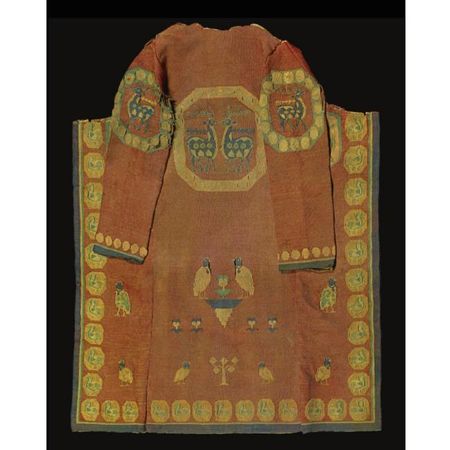

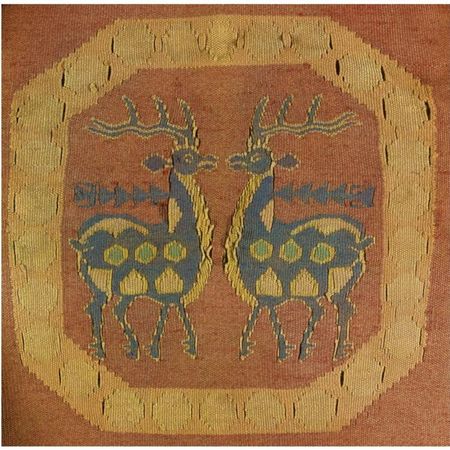

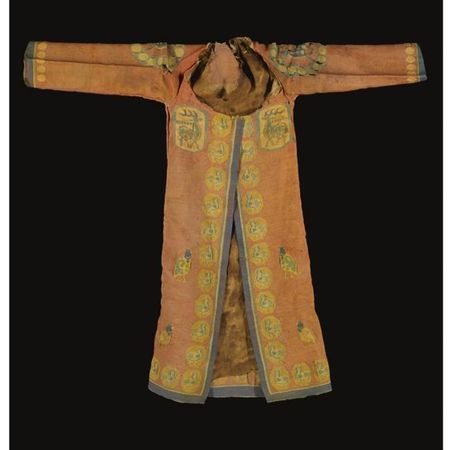

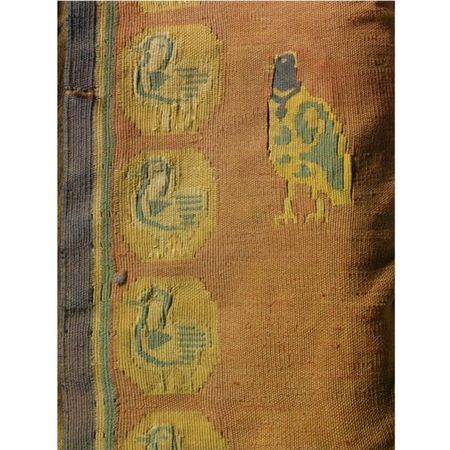

• Further top-selling sell lots include a rare 9th/10th century Soghdian split tapestry (kilim) coat with animal motifs from central Asia, which sold for £802,850 against an estimate of £100,000-120,000 and a rare 10th-11th century Fatimid Marble Jar-Stand (kilga) from Egypt, which sold for £457,250, almost six times its pre-sale high estimate (est. £60,000-80,000).

A rare Sogdian split tapestry (kilim) coat with animal motifs, Central Asia, 9th/10th Century. Photo: Sotheby's.

on red ground with yellow and green animal motifs, comprising gazelles at the shoulders within circular pattern, yellow disks along the sleeves, the length of the coat at the lapel with border of small birds and four larger dark-headed birds, to the back two large gazelles confronting each other within a medallion, two birds facing each other set upon a pyramid and carnation, two smaller birds surrounding a stylised tree and further border of small birds in roundels at bottom of coat, with silk lining - 112.7 by 123cm. max. Est. 100,000—120,000 GBP. Lot Sold 802,850 GBP

NOTE: Sogdian civilisation has been traced back to the 6th century BC but it was not until the 7th century AD that the Sogdians achieved semi-independent status. With this came economic prosperity and stability leading to lavish architectural and artistic patronage with palaces decorated with opulent wall paintings. The themes of their frescoes rely heavily on religious motifs, and occasionally literary themes focusing on the Aryan epics. Zoroastrian, Nestorian Christian, Manichean, Hindu and Buddhist motifs were depicted in styles borrowed from a variety of sources reflecting their extensive trading contacts: Sasanian, Central Asian, Far Eastern and Indian.

The Sogdians position on the trade routes of the Silk Road, which Sogdian merchants controlled from the 1st century AD onwards playing a major role negotiating between China and Central Asia, continued to be vital to their resources and holdings well into the 10th century.

A recurring motif in pictorial records of Sogdian clothing is the large medallion enclosing smaller "pearls", as evinced in the present example. This design can also be traced in figural representations in frescoes in western China from the 6th/7th centuries, see Cécile Beurdeley, Sur les Routes de la Soie, Fribourg, 1985, pp.116-117, no.116-118. The frescoes at the palace of Penjikent (extensively published in A.M.Beleniziki, Kunst der Sogden, Leipzig, 1980, pp.41-140) clearly illustrate the utilization of the circular theme.

Sogdian art is quite close in style to that of the Sasanians. It was the bird motif seen here that was the most commonly adopted design. Quinte-Curce, a first-century AD Roman historian, described the robes of the Persian satrapes as comprising a design of two birds threatening each other with their beaks (Beurdeley, Sur les Routes de la Soie, p.162). An example of this was found in tomb 134 in Turfan in 1969 together with a stele dated to 662 and is currently held by the Museum in Xinjiang, China. Although earlier in date, this is the closest published example to the present lot.

The majority of Sogdian textiles that have been found, such as those in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, are produced using silk. This adds to the rarity of the tunic here which is made of wool. The silk examples in the Hermitage have the same design with the roundels enclosing further discs. These medallions would encircle motifs of birds, wild boars, double-sided axes, and other animals.

A Carbon 14 test has confirmed the 9th-10th century dating.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F01%2F577050%2F66379918_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F04%2F00%2F119589%2F66268897_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F37%2F119589%2F66268549_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F86%2F30%2F119589%2F66187962_p.jpg)