Picasso's La Lecture Sells at Sotheby's for £25.2 Million in Sale Totalling £68.8 Million

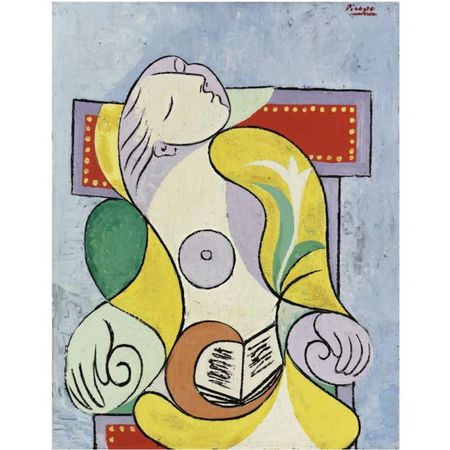

Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973), La Lecture, painted in January 1932, signed Picasso (upper right); inscribed 11 decembre M.CM.XXXII. on the reverse, oil on panel, 25 3/4 by 20 1/8 in. Estimate 12,000,000—18,000,000 GBP. Sold 25,241,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

LONDON.- Tonight, Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Evening sale was led by Pablo Picasso’s iconic 1932 painting of Marie-Thérèse Walter, La Lecture, which sold to a round of applause for £25,241,250 /$40,711,612 / €29,744,296, more than double the low estimate (est. £12 – 18 million/$18.5-27.8 million). Following a heated bidding contest that lasted six minutes among at least seven bidders, both on the phone and in the saleroom, the work finally sold to an anonymous buyer bidding over the telephone. Achieving a strong total of £68,834,400 / $111,023,004 / €81,114,475, well within the pre-sale estimate of £55,630,000 - 79,250,000**, the sale was 84.5% sold by value. The average lot value for the works sold this evening was £2.15 million/ $3.5 million.

Helena Newman, Chairman, Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Europe, said: “We were thrilled with the price achieved for Picasso’s La Lecture – an exceptional work from one of the artist’s most celebrated periods. The painting attracted strong pre-sale interest from across the globe, which was manifest in the depth of bidding we saw tonight - no fewer than seven bidders drove the price to a final £25.2 million. Across the sale as a whole, buyers came from 11 countries, with bidding from Asia, Russia, the US and Europe.”

Melanie Clore, Chairman, Sotheby’s Europe, said: “We look forward to continuing the sales this week Looking Closely on Thursday night, an exceptional private collection which is already attracting interest from collectors around the world.”

Looking Closely: A Private Collection comprises 60 lots estimated to fetch in excess of £40 million. Highlights from the sale include Salvador Dalí’s masterpiece Portrait de Paul Eluard (£3.5-5 million) and Frances Bacon’s triptych of Lucien Freud (est. £7-9 million).

Picasso’s La Lecture

The sale of La Lecture brought the painting to Europe for the first time since it was painted in 1932. It is one of a series of defining works in the artist’s oeuvre in which he introduces his young lover Marie-Thérèse Walter as a recognisable figure. The couple’s relationship was kept a well-guarded secret for many years, both on account of the fact that Picasso was then still married (to Olga Khokhlova, a Russian-Ukrainian dancer he had met on tour with Diaghilev) and because of Marie-Thérèse’s age (she was just 17 at the time). Until the period in which this work was painted, Marie-Thérèse only ever appeared in Picasso’s works in code, her features often embedded in the background of his paintings. But by the end of 1931, Picasso could no longer repress the creative impulse that his lover inspired, and over Christmas and New Year 1931 and ‘32, Marie-Thérèse emerged, for the first time, in fully recognisable, languorous, form.

PROVENANCE: (possibly) Paul Rosenberg & Co., Paris

Valentine Dudensing Gallery, New York (acquired by 1940)

Keith Warner, Fort Lauderdale & New York

Paul Rosenberg & Co., New York (acquired from the estate of the above in 1963)

Mr & Mrs David Lloyd Kreeger, Washington, D.C. (acquired from the above in January 1964)

Mr & Mrs James W. Alsdorf, Chicago (acquired by 1980)

Sale: Habsburg, Feldman, New York, 8th May 1989, lot 57

Private Collection

Acquired by the present owner in 1996

EXHIBITED: Paris, Galerie Georges Petit & Zurich, Kunsthaus, Exposition Picasso, 1932, no. 197 (in Paris); no. 202a (in Zurich) (as dating from 1931 and titled La Lecture interrompue)

New York, Valentine Dudensing Gallery, Three Spaniards: Gris, Miró, Picasso, 1940

Los Angeles, County Museum of History, Science and Art (on loan 1945-46)

Washington, D.C., Corcoran Gallery & Baltimore, Museum of Art, Selections from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. David Lloyd Kreeger, 1965, no. 21, illustrated in the catalogue

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective, 1980, illustrated in the catalogue (titled The Dream (Reading) and as dating from January 1932)

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: P. Gréguen, 'Picasso: Primitif Cérébral', in Cahiers d'Art, Paris, 1932, illustrated p. 114

J.L., 'Exhibitions of the Week: Three Spanish Painters, Gris, Miró, Picasso', in Art News, New York, 6th April 1940, illustrated p. 27

Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, Geneva & Paris, 1944, illustrated pl. 168 (titled Femme endormie and as dating from 1932)

Christian Zervos, Pablo Picasso, œuvres de 1926 à 1932, Paris, 1955, vol. 7, no. 363, illustrated pl. 158 (with incorrect medium and measurements, and as dating from January 1932)

Henri Dorra, The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. David Lloyd Kreeger, Washington, D.C., 1970, illustrated p. 77

Jean Leymarie, Picasso: Métamorphoses et unité, Geneva, 1971, illustrated p. 78 (as dating from January 1932)

Margy P. Sharpe, The Collection of Mr. & Mrs. David Lloyd Kreeger, Richmond, 1976, illustrated in colour p. 206 (titled La Lecture interrompue and as dating from 1932)

The Picasso Project, Picasso's Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture. Surrealism, 1930-1936, San Francisco, 1997, no. 32-002, illustrated p. 86 (with incorrect medium and as dating from January 1932)

Picasso Harlequin, 1917-1937 (exhibition catalogue), Complesso del Vittoriano, Rome, 2008-09, mentioned p. 204 (with incorrect medium and measurements)

Picasso by Picasso, His First Museum Exhibition 1932 (exhibition catalogue), Kunsthaus, Zurich, 2010-11, illustrated in a photograph of the 1932 Galerie Georges Petit exhibition p. 98; illustrated in colour p. 243 (as dating from 1932)

NOTE: Picasso's iconic paintings of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter reign supreme as the emblems of love, sex and desire in twentieth-century art. The sensual La Lecture, which is one of the most recognisable images among this landmark series from the beginning of 1932, essentially introduced the young woman as an extraordinary new presence in Picasso's life and his art. This exceptional work is one in a series of defining paintings in the artist's œuvre in which he depicts his lover asleep in an armchair, the curves of her body transformed into a sumptuous confection with colourful swirls and sweeping arabesques. Marie-Thérèse's potent mix of physical attractiveness and sexual naivety had an intoxicating effect on Picasso, and his rapturous desire for the girl brought about a wealth of images that have been acclaimed as the most erotic and emotionally uplifting compositions of his long career. Picasso's unleashed passion is nowhere more apparent than in the depictions of the sleeping beauty, the embodiment of tranquility and physical acquiescence. Similar to Le Rêve (fig. 1), painted only days apart, La Lecture is rich with signifiers of sexual availability, fertility and pleasure and exemplifies Picasso's creative power in full bloom.

Picasso first saw Marie-Thérèse (fig. 2) on the streets of Paris in 1927, when she was only seventeen years old, while he was entangled in an unhappy marriage to Olga Khokhlova. 'I was an innocent girl,' Walter remembered years later. 'I knew nothing - either of life or of Picasso... I had gone to do some shopping at the Galeries Lafayette, and Picasso saw me leaving the Metro. He simply took me by the arm and said, 'I am Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together' (quoted in Picasso and the Weeping Women (exhibition catalogue), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles & The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994, p. 143). The couple's relationship was kept a well-guarded secret for many years, both on account of Picasso's marriage to Olga and Marie-Thérèse's age. But the covertness of the affair only intensified Picasso's obsession with the girl, and many of his pictures, with their dramatic contrasts of light and dark, allude to their secret interludes held under cover of darkness.

La Lecture belongs to a group of works painted in January 1932 in anticipation of the major retrospective that Picasso was planning that coming June. It was during these preceding months that he first cast his artistic spotlight on the voluptuous blonde. Up until this point he had only made reference to his extramarital affair with Marie-Thérèse in code, sometimes embedding her symbolically in a composition or rendering her unmistakable profile as a feature of the background. But by the end of 1931, Picasso could no longer repress the creative impulse that his lover inspired, especially as his marriage grew increasingly unbearable. John Richardson explains that while Olga organised large holiday parties that December in an attempt to demonstrate family unity, Picasso was involved in an artistic blood-letting, painting violent or murderous depictions of his wife. The exercise was a catharsis, Richardson claims, that better enabled him to focus on a 'languorous, loving painting of a lilac-skinned Marie-Thérèse asleep' just in time for Christmas: 'On December 30, the day of the Christmas party, Picasso found time to turn her into a swirl of arabesques: a lunar octopus, which reminds us that he had associated her with the phases of the moon the previous summer. By January 2, Marie-Thérèse's moon face is full, her eyes stare us down. The fuzzy print in the open book that this moon goddess clutches in her anaconda arms signifies pubic hair. Over the next three weeks, Picasso produced a succession of large Marie-Thérèses, dozing in a chair with a red leather back, studded with brass nails' (J. Richardson, A Life of Picasso, Volume III, The Triumphant Years 1917-1932, New York, 2007, p. 466). Based on Richardson's description, we can deduce that La Lecture belongs to this group of paintings from January 1932. In the frenzy of holiday activity, Picasso must have mistakenly inscribed the reverse of this work with the date 11 decembre M.CM.XXXII., which cannot be correct as the painting was already exhibited from June until October 1932.

'When a man watches a woman asleep,' Picasso confessed, 'he tries to understand' (quoted in J. Richardson, A Life of Picasso, New York, 1991, vol. I, p. 317). The theme of the sleeping woman recurred in a series of works that explored his mistress in different poses, either fully recumbent (fig. 3) or seated. The image of sleep and the way in which Marie-Thérèse appears to lose herself in its oblivion links this work, via its association with the unconscious, to Picasso's most fertile Surrealist images. Roland Penrose, who was one of Picasso's Surrealist associates, said the following about these paintings: 'Most of these figures painted with flowing curves lie sleeping, their arms folded round their heads... The sleeper's breasts are round and fruitlike and her hands finish like the blades of summer grass. The profile of the face, usually with closed eyes, is drawn in one bold curve uniting forehead and nose above thick sensuous lips' (R. Penrose, Picasso, His Life and Work, London, 1958, p. 243). The suggestive imagery in La Lecture is not limited to the figure's body. Just as the lily is depicted as a symbol of her purity and fecundity, the open book in her lap is understood to be an allusion to her exposed genitalia, as are the hands in La Rêve and the musical instrument in Jeune femme à la mandoline (fig. 4).

'When I paint a woman in an armchair,' Picasso once recounted, 'the armchair implies old age or death... or else the armchair is there to protect her.' It is the latter sentiment that clearly governs these depictions of Marie-Thérèse, but as Judi Freeman explains, 'In the 1930s these chair-bound women directly responded to Matisse's work as well. Matisse painted many of his models in lavishly decorated interiors [fig. 5], often seating them on elaborately upholstered chairs or on divans' (J. Freeman in Picasso and the Weeping Women, op. cit., p. 157). While the differences between Picasso's and Matisse's treatment of this subject is readily apparent, Picasso was careful to distance himself from the work of his arch-rival. Picasso exhibited this work, together with Le Rêve (fig. 1), in a retrospective in Paris and Zurich in the summer and autumn 1932. At the Paris venue of this exhibition, he chose to hang his seated portraits of Marie-Thérèse, including the present work, alongside his Cubist and Surrealist compositions (fig. 6). Picasso's unusual placement of the pictures may have been intended to deflect immediate comparisons to Matisse's odalisques that had hung in the same gallery the prior year and to remind the audience of his undisputable originality.

It was on this occasion in Paris that Olga, upon seeing Picasso's numerous references to a specific face that was clearly not her own, was alerted to the presence of another woman in her husband's life. Until the exhibition, Picasso's relationship with Marie-Thérèse had been a secret affair, the evidence of which he had kept sealed away at the studio he maintained at Boisgeloup. He had purchased this property near Gisors in 1930 as a retreat, where he could escape from Olga and spend time alone with his mistress. The chateau at Boisegeloup was much larger than his studio in Paris, and the space allowed him to create the monumental plaster busts of Marie-Thérèse that were depicted in several paintings.

After this exhibition, Marie-Thérèse's features would become more readily identifiable in Picasso's art. Robert Rosenblum wrote about the young woman's symbolic unveiling: 'Marie-Thérèse, now firmly entrenched in both the city and country life of a lover twenty-eight years her senior, could at last emerge from the wings to center stage, where she could preside as a radiant deity, in new roles that changed from Madonna to sphinx, from odalisque to earth mother. At times her master seems to worship humbly at her shrine, capturing a fixed, confrontational stare of almost supernatural power; but more often, he becomes an ecstatic voyeur, who quietly captures his beloved, reading, meditating, catnapping, or surrendering to the deepest abandon of sleep' (R. Rosenblum in Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation (exhibition catalogue), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996, p. 342).

When Picasso included La Lecture in his retrospectives in Paris and Zurich in 1932, it was listed in the catalogue as available for sale. By April 1940 it came into the possession of the Valentine Dudensing Gallery in New York. The picture was eventually acquired by Keith Warner (1895-1959), owner of a leather manufacturing company and collector of works by Mondrian, Calder and Picasso that are now in the collections of major museums in the United States. In 1964, the insurance mogul and distinguished art collector David Lloyd Kreeger purchased La Lecture from Picasso's dealer Paul Rosenberg, who had by that time relocated his gallery to New York. Kreeger was an associate of the Chicago-based philanthropist James Alsdorf, who served on advisory boards to many cultural institutions throughout the United States and eventually acquired La Lecture for his own esteemed collection.

Fig. 1, Pablo Picasso, Le Rêve, 1932, oil on canvas, Private Collection, Las Vegas

Fig. 2, Marie-Thérèse Walter with her mother's dog, 1932. Photograph by Picasso, Collection Maya Picasso.

Fig. 3, Pablo Picasso, Femme nue, feuilles et buste, 1932, oil on canvas. Sold: Christie's, New York, 4th May 2010

Fig. 4, Pablo Picasso, Jeune fille à la mandoline, 1932, oil on panel, The University of Michigan Museum of Art, Gift of The Carey Walker Foundation

Fig. 5, Henri Matisse, Odalisque au tambourin, 1926, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fig. 6, Installation view of the Galerie Georges Petit in June 1932, the present work is visible in the upper left. Photograph Collection Reber

Other notable prices

• A further highlight of the sale was one of the most important works by Marino Marini ever to come to the market: his monumental sculpture of horse and rider L’idea del cavaliere sold for £4,185,250 / $6,750,390 / €4,931,900 (est. £3.7-4.5 million) to an anonymous. Similarly, Henry Moore’s important large-scale Reclining Connected Forms achieved £2,057,250 / $3,318,139/ €2,424,264 (est. £1.5-2.5 million) to an US buyer.

Marino Marini (1901 - 1980), L’idea del cavaliere , executed in 1955 and cast in bronze in an edition of 4. This work was also carved in wood in 1956, inscribed MM, numbered 3/3 and stamped with the foundry mark Fonderia d'Arte De Andreis, Milano, bronze, painted by the artist; height: 220cm.. Estimate 3,700,000—4,500,000 GBP. Sold 4,185,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York (acquired from the artist in 1964)

Jeffrey H. Loria, New York (acquired from the above in 1977)

Private Collection, Europe (acquired from the above)

Private Collection, U.S.A.

Acquired from the above by the present owner

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Patrick Waldberg, Herbert Read & Gualtieri di San Lazzaro, Marino Marini, Complete Works, New York, 1970, no. 332, edition catalogued p. 372; colour illustration of the wood example p. 185 (with incorrect measurements)

Carlo Pirovano, Marino Marini – Scultore, Milan, 1972, no. 338, edition catalogued and illustration of the wood example p. 168

Mercedes Precerutti Garberi, Marino Marini alla Galleria d'Arte Moderna di Milano, Milan, 1973, p. 165

Lorenzo Papi, Marino Marini. Impressioni di Lorenzo Papi, Ivrea, 1987, illustration of another cast n.p.

Giovanni Iovane, Marino Marini, Milan, 1990, p. 96

Marco Meneguzzo, Marino Marini – Il Museo alla Villa Reale di Milano, Milan, 1997, no. 84, p. 226

Fondazione Marino Marini, Marino Marini, Catalogue Raisonné of the Sculptures, Milan, 1998, no. 412b, colour illustration of another cast p. 286

NOTE: Equestrian images have a long and esteemed tradition in Western art. Throughout the centuries, paintings and sculptures of men on horseback, often depicting noble cavalrymen or generals mounted on their steed, celebrated the glories and victories of an era or an empire. But the sculptures of riders and horses that Marino Marini created after the Second World War are a radical departure from this tradition. Conceived in the midst of profound political transformation, Marini's riders are a response to the wave of uncertainty that engulfed civilisation during the Cold War. Marini was obsessed with making the horse and rider theme applicable to the contemporary age, and no other artist in the history of 20th century art came close to revitalising this age-old subject with such creativity and expressive force. His anonymous, highly abstracted horsemen eschew any pomp or pretence and are rich with psychological complexity and formal beauty. This monumental sculpture from 1955 of a rider and his horse, rigid with explosive tension, is a wonderful example of the artist's achievements in this area.

Marini's interest in the horse and rider theme initially derived from the Etruscan and classical Roman sculptures, such as the iconic equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, that he had seen as a young art student in Italy. His first serious artistic consideration of the theme occurred during the early 1930s, after travelling to Northern Europe where he saw the 11th century equestrian statue of Emperor Henry II in Bamberg cathedral (fig. 2). Marini's admiration for these medieval examples, as well as for Degas's sculptures of racehorses, the Italian Futurists' mechanised horses, and Picasso's terrified horse in Guernica, inspired him to explore equestrian themes in his art. Over the next several decades, Marini's horsemen became increasingly abstract, and the bodies of the horse and rider were simplified to their most elemental components. By the 1950s, when the present work was created, Marini developed what is largely considered his most powerful representations of this subject. Reflecting on the development of these sculptures, he wrote: 'In the end, my passion for the horse represented a personal research into a kind of visual architecture. The horse's form is the opposite of man's; the horse is horizontal, man is vertical... However, the concept changed over the years, and at a certain point what had been serene and tranquil became agitated and expressionistic' (quoted in Sam Hunter, Marino Marini, The Sculpture, New York, 1993, p. 78).

Remarkable and rare for its monumentality, this sculpture is further enhanced by its bright colouration. The choice of red and black pigment and the abrupt strokes with which it is applied recall the aesthetic of the German Expressionists as well as the polychrome totems of Native American tribal art. In contrast to an earlier large-scale bronze from 1949-50, The Town's Guardian Angel (fig. 3), which displays a steadier, more balanced composition, L'Idea del cavaliere demonstrates the expressive shift of Marini's art after the war. No longer satisfied with renderings of stoic figures on horseback, Marini, like many post-war Italian artists, and Giacometti, invested his work with an intensity and emotionalism that had not been present in his earlier sculpture. The shift was most pronounced in the Cavaliere series, in which the riders now seemed to freeze with terror or brace themselves for the imminent bucking of their horse. 'My equestrian figures are symbols of the anguish that I feel when I survey contemporary events,' Marini wrote about the development of these sculptures. 'Little by little, my horses become more restless, their riders less and less able to control them. Man and beast are both overcome by a catastrophe much like those that struck Sodom and Pompeii' (ibid., p. 60).

In his later years, Marini explained the evolution of the cavaliere in his art, noting how the horse and rider responded to the ever-changing tenor of world events. 'Equestrian statues have always served, through the centuries, a kind of epic purpose. They set out to exalt a triumphant hero... But the nature of the relationship which existed for centuries between man and the horse has changed, whether we think of the beast of burden that the ploughman leads to the drinking trough in a painting by the brothers Le Nain, or of the Percherons ridden by the horse-traders in Rosa Bonheur's famous picture, or again of the stallion that rears as it is spurred by one of the cavalrymen paintings by Géricault or Delacroix. In the past fifty years, this ancient relationship between man and beast has been entirely transformed. The horse has been replaced, in its economic and military functions, by the machine, the tractor, the automobile or the tank. It has become a prime symbol of sport or of decadent luxury, and, in the minds of most of our contemporaries, it is rapidly becoming a kind of lost myth (ibid. p. 24).

The present sculpture was originally executed in polychrome plaster, which is now in the Collezione d'Arte Religiosa Moderna, Musei Vaticani in Rome. Other casts from the edition of four bronzes are at the Museo Marino Marini in Milan and the San Diego Museum of Art. In 1956, Marini carved a unique painted wood version of this work, which was sold at Sotheby's New York in May 2007 (fig. 4).

Fig. 1, Marini in his studio, in front of the plaster model of the present work, 1962

Fig. 2, Equestrian Statue of Emperor Henry II, circa 1230, stone, Bamberg Cathedral, Bamberg

Fig. 3, Marino Marini, The Town's Guardian Angel, 1949-50, bronze (height: 172cm.), The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice

Fig. 4, Marino Marini, Idea del cavaliere, unique painted wood, 1956. Sold: Sotheby's, New York, 8th May 2007

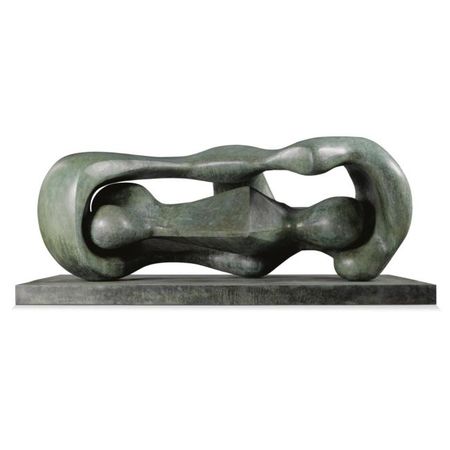

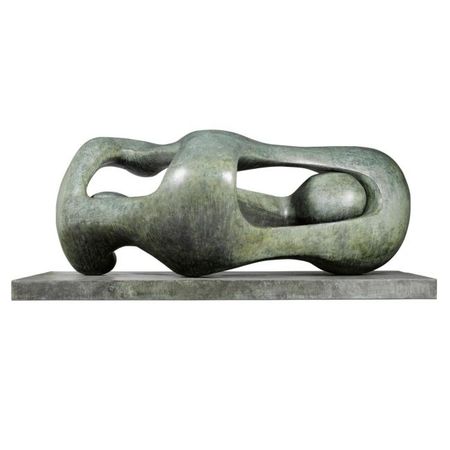

Henry Moore (1898 - 1986), Reclining Connected Forms, rxecuted in 1969 and cast in bronze in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist's proof; inscribed Moore and numbered 5/9; bronze, length: 224cm. Estimate 1,500,000—2,500,000 GBP. Sold 2,057,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: Lambeth Arts Limited (James H. Kirkman), London

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 1973

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore, Sculpture 1964-73, London, 1977, vol. 4, no. 612, illustrations of another cast p. 59 and pls. 150-153

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, London, 1977, illustrations of another cast pp. 62-66

David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore Sculpture, New York, 1981, nos. 494-496, illustrations of another cast pp. 228-229

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of The Henry Moore Foundation, London, 1998, no. 225, illustration of another cast p. 298

This work is recorded in the archives of the Henry Moore Foundation.

NOTE: Reclining Connected Forms is an important monumental sculpture, incorporating two recurring themes in Moore's art: a dichotomy between internal and external forms, and the related theme of mother and child. The composition consists of two reclining forms, one nestled inside the other, the larger shape gently curved around the smaller one, sheltering it in a protective gesture. The two forms are highly abstracted, the voluminous shape of the outer one standing in dynamic contrast with the sharper, angular form of the inner one.

Moore's investigations into the relationship of internal and external forms were particularly intense in the early 1950s, when he executed several vertical sculptures titled Upright Internal/External Form. In the present work, Moore revisits this theme, now presenting it in a reclining format. While it is executed with a high degree of abstraction, Reclining Connected Forms is clearly a continuation of the artist's interest in recumbent figures, as well as in the motif of the mother and child.

Deborah Emont-Scott wrote about the present composition: 'Moore's initial interest in the internal/external form was realised in a mid-1930s series of drawings of a Malangan figure from New Ireland, Oceania. Moore wrote: "... the carvings of New Ireland have, besides their vicious kind of vitality, a unique spatial sense, a bird-in-a-cage form". Through the decades, Moore turned from the vertical stance of his internal/external forms to renderings of this motif in a horizontal position, which now became a reclining figure. In this highly abstracted sculpture, the internal and external sections look more like a landscape element than a human figure. The undulating external form appears cave-like, its wall structure hollowed out through the natural force of wind or water. The interior element solidly rests in the embrace of the form that surrounds it. The reclining figure reads as a mother either with a foetus in her womb or with a child in her embrace. The child-like form is angular in contrast to the organic flow of the "mother". The diamond-shaped torso of the child differs sharply from the organic rhythms of the mother's form suggesting that it is still in the "rough", not yet completely shaped, but rather emerging, still to find its form' (D. Emont-Scott, in David Mitchinson (ed.), op. cit., 1998, pp. 298-299).

Other casts of this work are at the University of Adelaide in south Australia, Trinity College in Dublin, Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, New York, on Park Avenue, New York and at the Henry Moore Foundation, England. The 8-metre long version of Reclining Connected Forms, carved by Moore in travertine marble in 1974, is the largest carving in Moore's œuvre. It was formerly in the collection of The Maryland Institute, College of Art in Baltimore (fig. 1), and sold at Sotheby's New York in May 1990. It is now part of the CityCenter Fine Art Collection on public display in Las Vegas.

Fig. 1, Henry Moore, Large Reclining Connected Forms, 1974, travertine marble, on display in the City of Baltimore (formerly in the collection of The Maryland Institute, College of Art in Baltimore and now part of the CityCenter Fine Art Collection, Las Vegas)

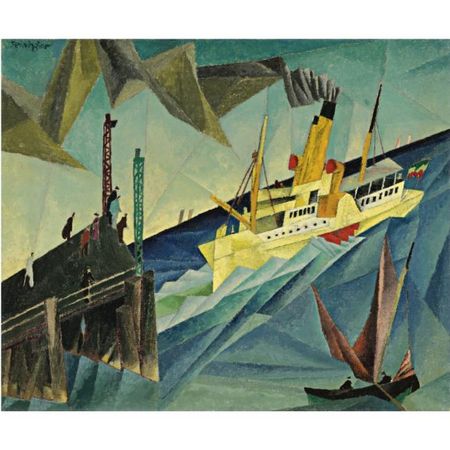

Lyonel Feininger’s oil on canvas Raddampfer am Landungssteg of 1912 reali£3,177,250 / $5,124,587 / €3,744,072, more than double its high estimate (est. £1-1.2 million), selling to a buyer in the saleroom following an extended battle among five bidders. This rare work, showing the artist’s inventiveness at the height of his involvement with the German Expressionist movement Die Brücke, had not appeared at auction since 1949.

Lyonel Feininger (1871 - 1956), Raddampfer am Landungssteg, painted in 1912., signed Feininger (upper left); signed Feininger and dated 1912 on the reverse, oil on canvas, 40 by 48cm. Estimate 1,000,000—1,200,000 GBP. Sold 3,177,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: Hugo Simon, Berlin & Paris

Kunsthandel Jacques Goudstikker NV, Amsterdam (on consignment from the above, by October 1933 and until at least December 1940)

Re-purchased by Kunsthandel Jacques Goudstikker NV from the administrators of the Aryanised dealership of Kunshandel voorheen J. Goudstikker NV, 9th June 1949 (their auction: Mak van Waay, Amsterdam, 4th October 1949, lot 216)

Mrs Meta Legat (née Ehrlich), Dreibergen & New York (purchased at the above sale for NGL 200)

Fritz Katz, New York (acquired from the above in 1972)

Thence by descent

EXHIBITED: Amsterdam, Kunsthandel Jacques Goudstikker NV, Tentoonstelling van Moderne Kunst, 1933

New Orleans, Museum of Art, German and Austrian Expressionism, 1975-76, no. 12

Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, Art in a Turbulent Era, 1978, illustrated in the catalogue

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Hans Hess, Lyonel Feininger, London, 1961, no. 95, illustrated p. 256

Robert Hughes, 'Art: The Anguish of the Northerners', in Time, New York, 27th March 1978, illustrated

Lyonel Feininger: Erlebnis und Vision die Reisen an die Ostsee 1892-1935 (exhibition catalogue), Museum Ostdeutsche Galerie, Regensburg & Kunsthalle, Bremen, 1992, illustrated p. 193

Achim Moeller of The Lyonel Feininger Project LLC has confirmed the authenticity of this work, under certificate number 424-01-05-11. The work will be included in volume one of his Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings.

This work is offered for sale in cooperation with the heir of Hugo Simon.

NOTE: Raddampfer am Landungssteg exemplifies Feininger's perspectival inventiveness at the height of his involvement with the German Expressionist group Die Brücke in 1912. The scene depicts a paddle steamer as it leaves the pier at Heringsdorf, a fashionable seaside resort on the Baltic island of Usedom. It was there during the summer of 1912 that Feininger refined his artistic style, devising innovative pictorial representations of the natural world. Feininger's new approach referenced the aesthetic of French Cubism, which had taken hold of the avant-garde across Europe, but applied his reshuffling of space to grander subjects in an attempt to synthesise the rhythms, forms, perspectives and colours of his surrounding environment.

Feininger explained the stylisation of this painting and others he did that year in the following terms: '1912 I worked entirely independently, striving to wrest the secrets of atmospheric perspective and light and shade gradation, likewise rhythm and balance between various objects, from Nature. My "cubism", to so miscall it, for it is the reverse of the French cubists' aims, is based upon the principle of monumentality, concentration to the absolutest extreme possible, of my visions... My pictures are ever nearing closer the Synthesis of the fugee... My "cubism" (again, falsely so-called); call it rather, if it must have a name, "prism-ism"' (quoted in H. Hess, op. cit., p. 56).

Between 1908 and 1913, Feininger visited Heringsdorf every summer, making excursions along the Pomeranian coastline. This maritime province of beaches, fishing ports and old Hanseatic villages provided Feiningner with a rich vein of subject-matter. His sketchbooks are filled with studies of sailing boats and imaginary galleons plying the inland seas, and also capture the distinctive atmospheric effects of the Baltic shores. In the present painting, Feininger depicts a contemporary scene that would have been instantly recognisable to the fashionable crowds from Berlin that gathered in Heringsdorf each summer. It shows the paddle steamer Freia pulling astern of the famous Kaiser-Wilhelm-Brucke, one of the largest and most elaborate piers in continental Europe at that time, with sailing boats on the horizon and in the foreground. Feininger returned to this subject in 1917 with his oil painting Odin I. Leviathan, depicting another of the Stettin-registered steamships that catered to the strong seasonal demand for coastal excursions along the Baltic.

Fig. 1, A postcard of the side-wheel steamer 'Freia' at Heringsdorf, 1911

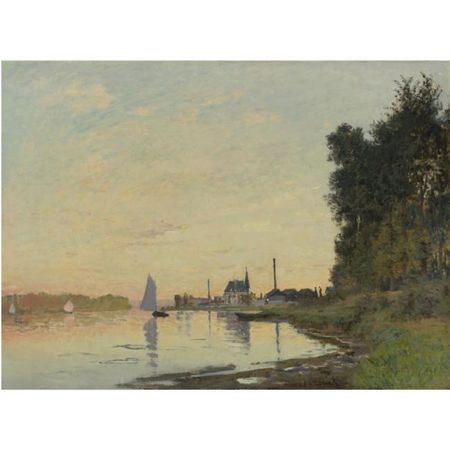

Claude Monet’s Argenteuil, Fin d’Après-Midi of 1872, one of the artist’s first major landscapes of his new home just outside of Paris sold for £3,401,250 /$5,485,876 /€4,008,034 (est. £3.5-4.5 million) to an anonymous.

Claude Monet (1840 - 1926), Argenteuil, Fin d’Après-Midi, painted in 1872, signed Claude Monet (lower right), oil on canvas, 60 by 81cm.. Estimate 3,500,000—4,500,000 GBP. Sold 3,401,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: (probably) Durand-Ruel, Paris (acquired from the artist in 1872)

Maurice Masson, Paris (sold: Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 22nd June 1911, lot 22)

Durand-Ruel & Bernheim Jeune, Paris (purchased jointly at the above sale)

Bernheim-Jeune, Paris (acquired from the above)

Comtesse Joachim Murat, Paris (acquired by 1912)

Marquis de Ludre, Paris

(possibly) I. Montaignac, Paris

Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York

Mrs Bernard F. Combemale (née Pamela Woolworth), New York (acquired by 1956. Sold: Christie's, London, 27th November, 1964, lot 42)

Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York (purchased at the above sale)

Jack Lasdon, New York (1964)

Acquavella Galleries, New York

Lawrence Lever, New York

The Estate of the above (sold: Christie's, New York, 15th May, 1979, lot 12)

Mr & Mrs Ralph C. Wilson, Jr., U.S.A.

Private Collection (sold: Christie's, New York, 14th November 1990, lot 13)

Purchased at the above sale by the present owner

EXHIBITED: Paris, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Collection Maurice Masson, 1911, no. 22

New York, The Museum of Modern Art & Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, Claude Monet, Seasons and Moments, 1960, no. 12

New York, Acquavella Galleries, Claude Monet, 1976, no. 11, illustrated in colour in the catalogue

Hiroshima, Prefectural Art Museum & Tokyo, The Bunkamura Museum of Art, Monet and Renoir: Two Great Impressionist Trends, 2003-04, no. 1, illustrated in colour in the catalogue

Brescia, Museo di Santa Giulia, Monet: la Senna, le ninfee. Il grande fiume e il nuovo secolo, 2004-05, no. 57, illustrated in colour in the catalogue (titled Argenteuil, tramonto)

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Camille Mauclair, Les Musées d'Europe. Le Luxembourg, Paris, 1927, pl. XIII, illustrated p. 61

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet, biographie et catalogue raisonné, Lausanne & Paris, 1974, vol. I, no. 224, illustrated p. 211

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet, catalogue raisonné, Lausanne & Paris, 1991, vol. V, no. 224, p. 26

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, catalogue raisonné, Cologne, 1996, vol. II, no. 224, illustrated in colour p. 99

NOTE: Argenteuil, fin d'après-midi, painted at the dawning of the Impressionist movement in the early 1870s, is one of Monet's first major landscapes of his new home, just outside of Paris. Argenteuil was famous for its annual regatta, and Monet took full advantage of the town's nautical resources to depict scenes of sailboats on the Seine. As Paul Hayes Tucker explains, '[By] 1871, when Monet moved there, his new home was not just some secluded little town outside of Paris but a celebrated center for pleasure boating in France. Boating meant Argenteuil and Argenteuil meant boating; the two were inseparable. The importance of this fact cannot be overemphasized, considering how much of Monet's work is devoted to sailboats on the Seine. He could have painted the barges or the fishing boats as Daubigny had when he came to neighbouring Bezons – for these vessels could still be seen coming and going on the river in Argenteuil in the 1870s – but they were old-fashioned. Rather, Monet chose to depict only those craft that represented the leisure activity of the day, and one of the most up-to-date aspects of the life of the town' (P. H. Tucker, Monet at Argenteuil, New Haven, 1982, pp. 90-91).

Painted in 1872, the present work was one of Monet's first major compositions depicting the theme of boats on the water and the popular promenade of Argenteuil. Monet devoted several canvases to the subject in the early 1870s, most famously in his renowned Le Havre composition, Impression, soleil levant, which would launch the avant-garde movement named after a derivative of that painting's title. In this scene, Monet is looking downstream and to the west, and the viewer is drawn in by the well-worn path that follows the river. To the right of the centre of the canvas is the Château Michelet, a grand Louis XIII-style home flanked by smokestacks visible in the distance.

Prior to 1873, France, along with the rest of western Europe, enjoyed a period of prosperity due to advances in industry, technology, wages and standards of living. Those who could afford it moved to once-rural areas that were now quickly and easily accessible from Paris by train. With their increased earnings, a leisure class of boaters and Sunday travellers emerged in these suburbs. Factories replaced inexpensive farmland and soon began to appear just outside the city. Monet and his fellow painters delighted in depicting the symbols of progress that emerged across the landscape. Daniel Wildenstein remarked in his catalogue raisonné on Monet's painting that this scene is no longer recognisable in present-day Argenteuil. As was the fate of many second-empire edifices on the outskirts of Paris, the château was eventually demolished and replaced by a factory. Monet's composition is thus a reminder of the radical transformations that the French countryside would undergo around the turn of the century.

As was characteristic of his best Impressionist landscapes, Monet painted Argenteuil, fin d'après-midi on location, setting up his easel along the river bank in order to capture the fleeting effects of light and shadow glistening on the surface of the water. His vantage here is of the boat-rental basin, a heavily trafficked area that provided one of the best views of the surrounding landscape. He captured this view in four canvases (Wildenstein nos. 221-224), including the present work and one in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (fig. 2). To the north on the river bank and directly opposite Monet's vantage here is the road bridge, famously featured in some of his best known compositions from this era (fig. 3). Monet's approach to these pictures was an exercise in celebrating the pleasures of modern life. According to Tucker, the depictions of the promenade, including the present work, 'are poems of tranquillity where the house and factories, the placid water of the Seine, and the peacefulness of the nearly deserted promenade speak for the idyllic harmony of the modern suburb' (ibid., p. 101).

Fig. 1, The road bridge at Argentuil, circa 1875

Fig. 2, Claude Monet, Le Promenade d'Argenteuil, 1872, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 3, Claude Monet, Le Port d'Argenteuil, 1872, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

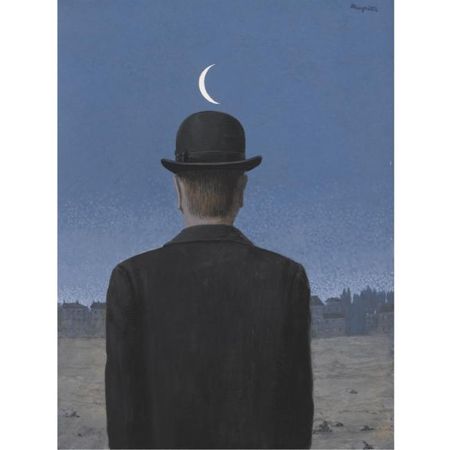

A new auction record was achieved tonight for a work on paper by Surrealist artist René Magritte with the sale of Le Maître d’École for £2,505,250 / $4,040,718 / €2,952,187 to an anonymous. This gouache on paper depicting Magritte’s iconic bowler-hatted man fetched a price over double the pre-sale estimate (est. £800,000 – 1.2 million) and double the previous record for a work on paper.

René Magritte (1898 - 1967), Le Maître d’École, executed in 1955, signed Magritte (upper right), gouache on paper, 33 by 24.8cm. Estimate 800,000—1,200,000 GBP. Sold 2,505,250 GBP.. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: Clare Boothe Luce, New York & Washington, D.C. (acquired from the artist)

Estate of the above (sold: Sotheby's, New York, 11th May, 1988, lot 171)

Purchased at the above sale by the present owner

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: David Sylvester (ed.), Sarah Whitfield & Michael Raeburn, René Magritte, Catalogue Raisonné, London, 1994, vol. IV, no. 1378, illustrated p. 168

NOTE: This striking gouache depicts Magritte's celebrated bowler-hatted man, seen here from the back, as if staring into the background, a motif that also appears in an oil of the same title painted in 1955. A crescent moon appears as if pasted low onto the sky just above the man, acting as his personal attribute. During this time Magritte also created a version of this image showing three bowler-hatted men, with a crescent moon above each figure (fig. 1). Talking about these two versions of the subject, Magritte wrote in a letter to Gaston Puel dated 3rd March 1955: 'I am certain of the value of certain images, such as 'The schoolmaster' or 'The masterpiece' for instance, because, while they may be of little interest to aesthetes, as poetic images they are the best to be found in the world' (quoted in D. Sylvester, op. cit., vol. III, p. 239).

The man is depicted here with his face turned towards the town-scape in the background, securing his all-important anonymity. David Sylvester wrote: 'This crucial anonymity is denied by the sort of attempts made to identify the men as civil servants or small-town lawyers or whatever – worst of all, as clones of Magritte himself. The common supposition that any bowler-hatted man painted by Magritte is something of a portrait of the artist gets things the wrong way round. Magritte painted numerous bowler-hatted men – most of them in his last twenty years-without giving one of them features unmistakably his own-this in spite of the fact that several paintings of his demonstrate that he had no inhibitions about clearly portraying his own face when he wanted to. But as Magritte's figure of the bowler-hatted man increased in fame, a tendency arose for photographers to persuade the artist to pose as a bowler-hatted man – privately his hat was usually a trilby – and it is, of course, the case that nowadays our image of an artist is usually based on what magazine photographs have made of him. So the equation of Magritte with the bowler-hatted man derives not from his own paintings but from other people's photographs [fig. 2]' (D. Sylvester, 'Golconde by René Magritte', in The Menil Collection, A selection from the Paleolithic to the Modern Era (exhibition catalogue), The Menil Collection, Houston, 1987, pp. 216-219).

As was often the case with Magritte's works, the title was found by his poet friend Louis Scutenaire. Regarding the image itself, David Sylvester explained its origins: 'The source of the image was an observation Magritte had made a year or so before in the company of Paul Colinet, and which he recalled in a letter to Colinet written around the middle of March which begins with reflections on the nature of genius. Magritte's belief, so he told Colinet, was that genius was not about having magnificent ideas but about recognizing them. "For instance, I had a magnificent idea without realizing this, nor did you, when I pointed out to you a year or two ago, that the moon in certain positions was exactly above a chimney-stack or a tree. At the time, we thought this 'droll', 'amusing' but of little interest. Thanks to the new pictures: The girls of the sky, The evening gown, The schoolmaster and The masterpiece, we can now display genius, if we realize that the 'droll' idea is in fact magnificent"' (ibid., p. 239).

The first owner of this work was Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987), an American writer, journalist, ambassador and Congresswoman. She wrote for the theatre, film and magazines, and was also the editor of fashion magazines including Vogue and Vanity Fair. After the outbreak of the Second World War, Luce left her career as an editor and travelled to Europe and the Far East, where she worked as a war journalist. In the 1940s she held a seat in the U.S. Congress, and in 1953 became the U.S. Ambassador to Italy. Luce owned several gouaches by Magritte, acquired directly from the artist. After her death in 1987, her works by Magritte and Dalí were sold at Sotheby's New York.

Fig. 1, René Magritte, Le Chef-d'œuvre ou les mystères de l'horizon, 1955, oil on canvas, Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles

Fig. 2, René Magritte, photographed in Brussels in 1965

A record price in sterling was achieved for Giorgio Morandi’s Natura Morta, which sold for £1,385,250 / $2,234,270 /€1,632,379 (est. £800,000- £1.2 million).

Giorgio Morandi (1890 - 1964), Natura Morta, painted in 1952, signed Morandi (lower left), oil on canvas, 40 by 50.5cm. Estimate 800,000—1,200,000 GBP. Sold 1,385,250 GBP. photo Sotheby's

PROVENANCE: José Luis & Beatriz Plaza, Caracas (acquired from the artist. Sold: Sotheby's, London, Giorgio Morandi, Paintings from the José Luis and Beatriz Plaza Collection, 9th December 1997, lot 316)

Purchased at the above sale by the present owner

EXHIBITED: Caracas, Fundación Mendoza, Homenaje a Giorgio Morandi, 1965, no. 10, illustrated in colour in the catalogue

Caracas, Fundación Mendoza, Giorgio Morandi, un homenaje, 1986, no. 16

Caracas, Fundación Mendoza, Homenaje a José Luis Plaza, 1991, no. 14

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES; Architectural Review, London, February 1971, illustrated

Lamberto Vitali, Morandi, catalogo generale, dipinti, Milan, 1977, vol. II, no. 808, illustrated

NOTE: Morandi's Natura morta of 1952 is a beautiful exemple of the artist's investigation into the spatial relationships between everyday objects, in this instance including bottles and a large pitcher. Negative space between the objects assumes confrontational immediacy and shadows are reduced to quivering outlines that frame simplified shapes of primary hues, while the luminosity of the central pair of white bottles resonates with the translucent grey backdrop. The deliberate play between what is known and what can only be guessed at is at the heart of Morandi's fascination with the visible world. Increasingly he became absorbed in creating permutations of the same objects, and we witness the same leitmotifs repeated time and again. The tall, slender bottles give the composition a sense of grace and classical beauty, while at the same time providing a dynamic contrast with the darker objects behind them.

Giorgio Morandi's meticulously composed still-lifes dominated in his painting throughout his career. Like other painters of his generation, he looked at the Italian art of the early Renaissance with fresh eyes, simultaneously conscious of the legacy of tradition as well as the regional and rustic aspects of his Italian cultural heritage. Additionally vital was the legacy of Paul Cézanne, whose intense focus on reality and individual way of seeing encouraged Morandi to discover the simple geometric solidity of everyday objects. This was to become his subject, although his style moved through several very distinct phases. The objects, invariably household items such as bottles, jars, pitchers and bowls, were laid out with the calculated precision of a classical composition, yet the way in which they are painted establishes their presence as self-contained forms in space.

Sold by lot: 76.2%

Sold by value: 84.5%

Of the 42 lots offered, 32 sold

Over 93% of the sold lots tonight achieved prices at or above their estimate

Average lot value: £2.15 million / $3.5 million

15 works sold for over £1 million, 28 sold for over $1 million

* Please note that Sotheby’s uses HSBC Bank Mid-Market Exchange Rate against Sterling Which for today was 1GBP = 1.61 USD

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F57%2F119589%2F64370738_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F36%2F03%2F119589%2F64361206_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F92%2F119589%2F61703506_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F80%2F577050%2F61028908_o.jpg)